Stephen Baxter the scholar: an appreciation

Julia Smith (Chichele Professor of Medieval History emerita)

I can’t remember when I first met Stephen Baxter, although it was certainly well before his appointment in 2014 as an Associate Professor in the History Faculty and the Barron Fellow in Medieval History at St Peter’s College. Already an established scholar in 2014, he took up the position with ten years’ experience teaching medieval history in KCL, and it must have been fairly early in those London years that I had been introduced to him. I did not know him at all well, though, and it was only after I arrived in Oxford two years later, in 2016, to take up the Chichele Chair of Medieval History, that I began to understand that his appointment not only rested on his well-founded reputation as a scholar of distinction, but also his great skill as a communicator. That ability simultaneously to explain and enthuse had made him a stellar teacher at KCL and also a ‘talking head’ with a string of significant radio and TV credits to his name.

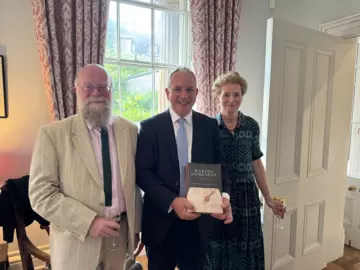

The Stephen of 2014 can fairly be described as a mid-career scholar, one who had mastered his craft and the rules of the game, but not yet one of commanding authority in the field. That, though, is exactly what he became in the course of his Oxford career, and the lasting monument to his reputation will be his chapters in Making Domesday: Intelligent Power in Conquered England, published just last year (2025) by Oxford University Press. His section of this collaboratively written book is the culmination of an intellectual project he had set himself many years previously, one the seeds of which are clearly visible in his DPhil thesis of 2002.

Eleventh-century England in the decades either side of the Norman Conquest was the field in which Stephen has made such a huge impact, an impact which will endure. Yet to choose to work on the political history of eleventh-century England, as he did, was hardly the sort of uncharted territory that novice researchers usually claim as their own. Many eminent historians had left their mark on it in previous decades; one might reasonably have steered a doctoral student away from such a crowded—and contested—field. But Stephen chose to write his DPhil on ‘The Leofwinesons: power, property and patronage in the early English kingdom’ which, after revision, was published as The Earls of Mercia: Lordship and Power in Late Anglo-Saxon England in 2007.

Stephen’s choice of research topic signalled the strength of his ambitious intellect and the resourceful creativity he brought to his work. Observers of academic sartorial fashions will have noticed that, unlike most anorak-wearing colleagues, Stephen preferred a tan-coloured overcoat with a dark brown velvet collar for his winter outerwear. Such a coat would not look out of place in the City of London, and indeed, academic research and teaching was Stephen’s second career. Having achieved a First in History at Wadham in 1991, he then went into the City. After three years as a research analyst with the PA Consulting Group, he moved to Schroders in 1995, where he was an Executive in their European Corporate Finance Division. Here, he worked as part of the small team which advised the Hungarian Privatization and State Holding Company on how to go about privatizing the Hungarian electricity industry in the aftermath of the collapse of the Communist regime. When he returned to Oxford as a graduate student in 1997, he brought with him not only a taste for City coats but also attributes acquired and skills honed in this utterly different environment.

In retrospect, Stephen was clear-sighted about the value of this experience to his formation as a historian. That value, in his estimation, was fourfold, as he explained in his letter of application to Oxford: “First, by working in Hungary in the early 1990s, I gained first-hand experience of a modern society undergoing momentous social and political upheaval. Second, I learned how to work efficiently under pressure for sustained periods of time; how to analyse evidence with rigour and precision; and how to communicate complex ideas to varied audiences using a variety of different media. Third, I spent a lot of time with senior management and government officials, and learned a great deal about how and why certain organisations function successfully. Fourth, I learned that companionship and trust are essential prerequisites for effective teamwork.” All those who were taught by Stephen, learned from his research or worked with him as a colleague will recognize these qualities in the historian they esteemed so highly.

As with any scholar’s curriculum vitae, Stephen’s publications of books and articles form a sequential, chronologically ordered list. But they can also be considered from another aspect: the unfurling from bud to flower of a single, driving method: the use of databases and spreadsheets as central tools of historical analysis, as applicable to eleventh-century England as to the Hungarian electricity sector. Statistical analysis presented through tables, figures, diagrams and maps underpins the argument of his first book, The Earls of Mercia. His role in creating the invaluable online ‘Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England’ ( https://pase.ac.uk/) drew medieval historians’ attention to the advantages of using computers to handle ‘big data’ collated from many different textual sources. His most recent—sadly the last—publication brings the many strands of his earlier work together in both the chapters he wrote alone and those written in conjunction with his co-authors in Making Domesday. This monument of scholarship combines the rigour and precision of Stephen’s exhaustive computer-assisted analysis with committed, collaborative teamwork with Julia Crick and Chris Lewis, his co-authors, and draws too on Stephen’s shrewd grasp of the institutional and interpersonal dynamics of complex organisations and governance. Making Domesday confirms how prescient that self-assessment of 2014 was. Stephen lived to celebrate the book’s publication at launch events in Oxford and London, but not, sadly to read reviews of it.

I last saw Stephen shortly after the launch parties and he was in good spirits. We chatted animatedly about the summer that stretched ahead, rather than about academic work. Those memories of him have now acquired a poignancy: I shall treasure them henceforth.