Samuel Ajayi Crowther, Black Victorians and the Future of Africa

Key words: Migration, Empire, Business, Identity, Liberty, Religion, Ideas, Role of individuals in encouraging/inhibiting change

Samuel Ajayi Crowther was probably the most prominent African involved in missionary activity in the nineteenth-century, but he was not the only one who played an important role in ‘spreading the gospel’. Who were the Africans that joined missions in the nineteenth-century? Why were mission societies initially so keen to recruit them? And what were these Africans thinking about the future of Africa?

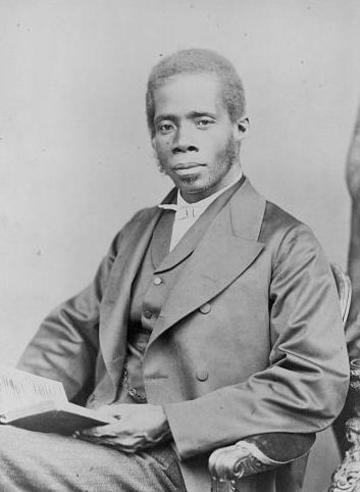

Samuel Crowther was consecrated bishop of West Africa in 1864 – he was the first African to hold such a high position in the Anglican Church. Crowther’s life story – that of slave turned bishop – reflected the experiences of a larger group of Africans whose life had been changed by the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Freed by the British Preventive Squadron from slave-ships on the way to the Americas, many were resettled in Sierra Leone, converted to Christianity and underwent formal school education. It was from among this group of Africans and their descendants that many missionaries were recruited. Starting from the late 1830s, ‘liberated Africans’ returned to their homelands in present-day Nigeria. With European missionaries, they established mission stations in Badagry, Lagos, and Abeokuta.

Africans played a crucial role in missions founded by Europeans and also established missions on their own. In the 1850s, British missionaries Anna and David Hinderer were joined in their mission station in Ibadan by the Africans Henry Johnson, William Allen and Daniel Olubi. They were preaching in the streets and built relationships to local authorities and prominent citizens. In 1857, Samuel Crowther established the Niger Mission with another African, Rev. J.C. Taylor.

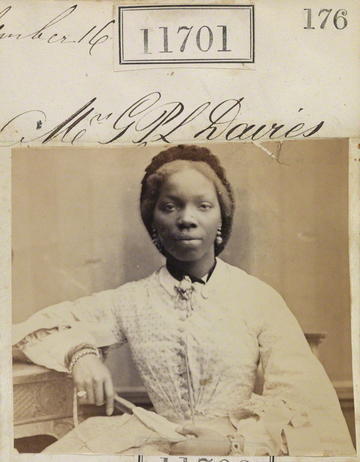

However, not all of this group of educated Africans became missionaries. Many were involved in the booming trade in palm oil and kernels, which was connected to the colonial presence, and some held important positions in the emerging colonial state. These educated Africans were anglicised in language, dress, names and mannerisms, and are sometimes referred to as Black Victorians or Black Englishmen (this example shows JPL Davies and Sarah Forbes Bonetta. She was a Yoruba princess and goddaughter of Queen Victoria, he was a wealthy businessman.

For most of the nineteenth-century, the Church Missionary Society (CMS), saw educated Africans as the ideal agents to spread the faith. When returning to those places to which they traced their origin, educated Africans could be agents of Christianity and, through their way of living, show the supposed advantages of the western way of life to fellow Africans.

However, less than 20 years after Crowther’s consecration, European missionaries’ attitude towards educated Africans changed. From the 1880s onwards, racist views on the capacities of Africans were expressed more frequently and more prominently (see British ideas of racial superiority). In 1890, two European missionaries accused a number of African pastors of fraud, ignorance and immorality and held Crowther responsible for their alleged behaviour. As a consequence, Bishop Crowther was pressured out of the Niger mission and his bishopric was placed under the supervision of European secretaries.

Crowther’s removal was a shock for these educated Africans. It mirrored racial discrimination African traders were facing when trading palm oil. Crowther’s ousting led to the formation of African churches which were independent from European missions. The formation of such independent churches reflected growing ideas amongst Africans about self-determination and African leadership. Some sought to Africanise Christianity, for instance by including African songs in mass, but also by changes that would include local religious ideas and practices.

At the time when Crowther was removed from the Niger mission, more radical ideas about African self-determination were gaining popularity among educated Africans. Edward Wilmot Blyden questioned whether assimilation to European ideals of ‘civilization’ would help or hinder Africa’s future. He instead stressed the uniqueness of Africans, and saw the continent’s future in the hands of African leaders who would include only useful elements of western culture. He also promoted unity among Africans and was one of the pioneers of Pan-Africanist thought.

Questions for classroom discussion

- In what ways were Africans crucial for missionary activity in West Africa?

- Why were Africans severing ties with European missions in the late nineteenth-century?

Background for teachers and further reading

This teaching resource aims to highlight African agency in missionary activity, and to point to the history of the educated elite more generally. It moreover seeks to complicate narrations of a unilateral transfer of ideas from Europe to Africa – it gives a glimpse into the intellectual history of West Africa and shows how Africans engaged with and challenged ‘western’ ideas. It illustrates how Africans were alarmed by changing British attitudes towards them – attitudes which were informed by increasing racial discrimination from the 1880s onwards. The case of Jaja of Opobo illustrates how British traders sought to eliminate African competition in the palm oil trade. Besides Jaja of Opobo, many educated Africans were engaged in the trade of palm oil, such as J.P.L. Davies. This resource also refers to changing conditions for Africans trading on the Niger when stating “viewing all that has happened and is happening, in the course of the present year”.

This source thus brings missionary activity together with commercial activity and illustrates the changing climate on the West African Coast from the 1880s onwards.

Clarification: CMS refers to the Church Missionary Society, which was associated with the Anglican Church.

African newspapers reporting on Crowther’s replacement and the Niger Mission in 1890:

“The importance of the future of that mission in connection with the race question cannot be overstated. Men are now asking everywhere whether it is really the intention of the Committee of the CMS, viewing all that has happened and is happening, in the course of the present year, to eliminate completely all native and (black) foreign element from the agency and direction of a mission which has been under the guidance of Bishop Crowther and his fellow native assistants during a period of over thirty years.”

Sierra Leone Weekly News, 11. October 1890, p. 5.

The Dictionary of African Christian Biography (http://www.dacb.org/) is an online resource that brings together biographies of Africans involved in missionary activity.

Rev. J.C. Taylor: http://www.dacb.org/stories/nigeria/taylor_jc3.html [20/6/2017]

Daniel Olubi: http://www.dacb.org/stories/nigeria/olubi_daniel2.html [20/6/2017]

Henry Johnson: http://www.dacb.org/stories/nigeria/johnson_henry.html [20/6/2017]

Figure 1 - Bishop Samuel Ajayi Crowther (1867)

Figure 2 - Yoruba Princess Sara Forbes Bonetta (15 September 1862)

Figure 3 - Edward Wilmot Blyden

Author Details

Dr Katharina Oke (Former DPhil candidate in Global History at the University of Oxford, working on Nigerian history)

Katharina is now Lecturer in Modern African History at Kings College London