Masters Dissertation Prizes 2021-22

Each year the Faculty of History awards prizes to those graduate students who have achieved the best performance overall within their cohort as well as those that have produced the best disseration within their cohorts.

Below are those who were awarded these prizes for the academic year 2021-22. A number of the students have written small summaries of their dissertations, which can be found at the bottom of the page.

Congratulations to all those awarded!

Best performance in cohort:

- MSt/MPhil History

- Ananya Malhotra

- Euan Huey - Making Morisco Spaces in the Imperial City: Toledo, 1570 – c. 1610.

- MSt/MPhil Late Antique and Byzantine Studies

- Frederick Bird - A Critical Edition of Georgius Pisides, Epigrammata with Introduction and Commentary

Best dissertation in cohort:

- MSt/MPhil History

- Clare Whitton (Medieval History) - 'San Gennaro and his Miraculous blood'

- Elliot Jordan (Early Modern History) - 'Spanish Blades': English Military Theory, the Spanish Threat and the Military Revolution, c.1558-1604'

- Harrison Goohs (British and European History 1700-1850) - 'German Freedom in a Revolutionary Epoch: The Congress of Rastatt (1797-1799) and End of an Empire'

- Alice Reffin (Modern British History) - 'Drawing the Empire or the Nation? Imagining the Irish Free State in the Posters of the Empire Marketing Board'

- Amanda DeMarco (Modern European History) - 'Constructing Socialist Internationalism: Shanghai Returnees and the GDR’s Vision of China, 1945–1957'

- Grady Owens (History of War) - 'Collegiate Martiality: The American Collegiate Experience and its Influences on Students and Administrators during the First World War'

- Thomas Noriega (Intellectual History) - 'Abounds with Scotticisms': Plato Studies in Enlightenment Scotland'

- Rosa Pouakouyou (Women's, Gender, and Queer History) - 'Carving out space in the women’s movement: Northern Ireland and Spare Rib Magazine, 1980-85'

- Pádraig Nolan (Women's, Gender, and Queer History) - 'Contingent Destination: Michael Dillon, Harold Gillies, and the Pre-Transsexual History of Medical Transition in Britain 1946-1955'

- Sara Green (MSt Global and Imperial History) - “Tear off the veil that still hides mores, customs and ideas”: Sexuality, racialised femininities and problematising Islam in the French Algerian Ethnographic Imaginaire, 1881-1931

- Krystof Jirku (MSc Economic and Social History) - "Forecasting Neo-Liberal Reform": Prognosticism, Technocracy, and Economic Theory in Normalisation- and Transformation-Era Czechoslovakia

- Jingyang Rui (MPhil Economic and Social History) - 'Feast or Famine: The Economic Polarizing Effect of China’s Non-Native Office Appointment System'

- Antony Hollingworth (MSc History of Science, Medicine, and Technology) - 'The introduction of a diphtheria immunisation programme during a time of war'

- Margaret Clipson (MSt History of Art and Visual Culture) - 'Framing Devotion: Architectural Symbolism in Royal English Gothic Manuscripts'

MSt/MPhil History

Euan Huey - Making Morisco Spaces in the Imperial City: Toledo, 1570 – c. 1610.

(Joris Hoefnagel (drawing), Frans Hogenberg (engraving) ‘View of Toledo’ in G. Braun, Civitatis Orbis Terrarum, vol. I, 3, 1572)

In 1570, the Spanish Crown began to forcibly relocate from Granada thousands of converts from Islam to Christianity, known as Moriscos, across the Kingdom of Castile. Mostly converted through force and coercion, Granadan Moriscos were widely suspected of secretly maintaining their Islamic faith and were outwardly attached to its cultural markers, such as the Arabic language. Their forced resettlement attempted to eradicate their attachment to customs and beliefs associated with Islam by assimilating this minority into Christian society.

This was part of a broader religious undertaking by the Spanish Crown in the long sixteenth-century, which also involved the expulsion of the Jews in 1492, frequent military contestation with the Ottomans in the Mediterranean and the spread of Christianity in Africa, Asia and the Americas by Spanish and Portuguese missions.

Toledo, the spiritual and ecclesiastical centre of the Iberian Peninsula, became home to almost 4,000 Moriscos by the time of their ultimate expulsion from the Peninsula in 1610. Faced with surveillance, inquisitorial persecutions, and restrictions to mobility, residency and employment, Moriscos made this hostile and unfamiliar city their home in the forty-year period between resettlement and expulsion. How Moriscos navigated this was the focus of my masters dissertation.

Through a spatial analysis that considered how Moriscos responded to, interacted with and perceived of different, yet intersecting, layers of space – the home, the neighbourhood and the city – my dissertation demonstrated the ways that Moriscos used their agency to manipulate these spaces and alter their intended uses and meanings. This analysis enabled an appreciation of how Moriscos engaged with a precarious and uncertain situation in creative and lively ways in order to survive, ascend and, at times, resist the efforts of the Crown to assimilate them.

Based on a critical reading of the records of the Inquisition, this project attempted to subvert inquisitorial filters and recover the voices and perspectives of Moriscos from the archive. Further, focusing on Toledo sought to contribute to a ground-up historiography that focuses on local and regional studies in order to avoid essentialising Moriscos as geographically uniform. Dr Stephanie Cavanaugh’s, Morisco Conversions: Belonging, Status, and Legal Action in Early Modern Valladolid (forthcoming), was a tremendous inspiration and it was a privilege to have her co-supervise this dissertation.

While I am no longer working on the Morisco presence in Toledo for my doctoral research, I am continuing to explore questions related to the relationship between Islam and the Iberian world in the context of imperial expansion into Southeast Asia in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

MSt/MPhil Late Antique and Byzantine Studies

Frederick Bird - A Critical Edition of Georgius Pisides, Epigrammata with Introduction and Commentary

My MPhil thesis focuses on the one hundred and twenty surviving epigrams of the seventh-century Byzantine poet Georgius Pisides. Pisides, who lived under the rule of Emperor Heraclius I (610–641), remained one of the best-known poets throughout the Byzantine period. Pisides’ epigrams are short poems which were to be read as inscriptions beneath icons of saints, on the doors of churches or in other physical locations.

None of Pisides’ epigrams survives in situ: all of the stones, wood and paintings which bore his work have long since been lost or destroyed. Nor do we have the original book in which he first wrote the epigrams. Such has been the fate of the vast majority of Byzantine literature. Fortunately, however, the texts have been preserved into modernity thanks to the diligence of many mediaeval scribes in making manuscript copies (and copies of copies, et cetera) of this body of poetry.

Despite their care in copying out a text, scribes were not perfect. Consequently there are many errors in the copies that they made. It is the task of the modern scholar to identify and eliminate errors from the text, in an attempt to restore it to the form in which the author left it.

I have been able to eliminate some errors from the texts of the epigrams by comparing the existing manuscripts and searching for readings which are error-free. The increasing number of manuscripts with digital reproductions available online has meant that I have so far been able to consult all but one of the twenty-six known extant manuscripts of the epigrams. I have found that collating the manuscripts is often a fairly systematic and ‘scientific’ process which is most rewarding when one finds a reading which shines out from the others as being most clearly correct.

Sometimes, however, when all the existing manuscripts offer readings which are manifestly incorrect, I have had to resort to a more ‘artistic’—and usually more speculative—method; having reached a dead-end when all the manuscripts are corrupt, I have needed to make an educated guess based on the available evidence as to what I think Pisides is most likely to have written.

I present the results of my manuscript analysis by printing a revised text of the epigrams with apparatus criticus, for the first time with a full English translation.

The text is preceded by an introduction in several parts, and followed by a line-by-line commentary. In these two sections of my thesis, I explain that the focus of the epigrams is primarily religious, but that within the broad scope of Byzantine Christianity they treat many different subjects, including the life of Christ, Christian festivals, biblical figures, passages from the Bible, churches and Late Antique saints. I have sought to draw attention to some of the defining characteristics of Pisides’ poetic craft, such as his use of semantic ambiguity and oxymoron, as well as his clever puns on subjects’ names. In these sections I also discuss the historical background, his literary sources and matters of poetic metre.

I hope to publish an expanded version of my thesis in the near future, following a series of shorter articles which I have written as off-shoots of my studies on Pisides at Oxford and which are being published in Austrian and Italian journals this year.

I am very grateful to Marc Lauxtermann, who suggested that I work on this project and who provided helpful and insightful advice while supervising me, as well as to Monica Hellström, Mary Whitby and Alberto Ravani, who have all given me valuable guidance in the last couple of years.

Medieval History

Clare Whitton - 'San Gennaro and his Miraculous blood'

Bust of Januarius, or “San Gennaro”

On September 19th, December 16th and the Saturday before the first Sunday in May, the blood of St. Januarius liquifies in Naples sparking annual religious processions and city-wide celebrations. Januarius, or “San Gennaro” as he is most often referred, is an elusive figure. Little is known about his legend beyond the story of his martyrdom. In the year 305, Bishop Januarius refused to sacrifice to the Roman gods, thereby condemning himself and a handful of companions to death. He survived a fire and wild beasts, but was ultimately beheaded under Emperor Diocletian. The liquefaction of his blood, however, is not documented until 1389, approximately 1,000 years after his death. This blood miracle became the quintessential feature of San Gennaro’s cult in the medieval period and continues into modern times.

This dissertation examines the multi-faceted uses and understandings of the blood miracle from the first record of the liquefaction in 1389 until the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 1631. After the eruption of Vesuvius, Gennaro’s cult changes substantially, including the establishment of a third feast day and a highlighted importance placed on Gennaro’s role as defender against Vesuvius. Consequently, previous aspects of Gennaro’s cult, such as his translatio feast and a pig contest, became less important. Previous historiography on San Gennaro’s cult reflects this; research on the Neapolitan saint is predominantly focused on his cult post-1631. In this dissertation, I aimed to challenge this focus and highlight cultic activity prior to Vesuvius’ eruption. This 242-year span allows us to identify and trace various uses for Gennaro’s relics, including bolstering the political authority of the Angevin dynasty and strengthening Neapolitan autonomy in the face of the Spanish and Roman Inquisitions. The material nature of the blood miracle also sparked theological discussions on resurrection, sacrifice and the ways in which God displayed his favor for Naples.

For example, the May translatio feast exemplifies how the blood miracle fostered a communal, Neapolitan identity and raised theological questions on sacrifice. This May feast commemorates the translation of Gennaro’s head and blood relics, which occurred sometime in the Late Antique Period when they were triumphantly paraded into Naples. By 1377, this feast was a large, theatrical event referred to as the festa dell’inghirlandati, or the feast of the garlanded priests. The clergy, adorned in garland and flowers, processed with Gennaro’s blood and head from the cathedral to the Church of St. Clare. In medieval and early modern texts, the “formula” for a liquefaction was clear: the head and blood must be brought together to spark the blood miracle, just as the head and blood were reunited centuries prior. This formula triggered the liquefaction, the resurrection of Gennaro’s blood from solid to liquid, dead to alive. Gennaro was once again walking the streets of Naples as he had done centuries prior. At the same time, a pig contest was being held in the cathedral. A live pig, smothered in butter and fat, was hung from the cathedral’s ceiling and lowered into a crowd of a few, lucky chosen men. These men were allowed to pull at the pig and whoever successfully pulled the animal down won the pig as a prize. The raucous game, which was ultimately banned, encouraged the communal aspect of this feast therefore aided the creation of a Neapolitan identity.

I continue to work on the cult of San Gennaro in my DPhil studies at Oxford. I will be investigating the cult over a larger span of time to trace the evolution of devotion to San Gennaro in Naples and the surrounding regions.

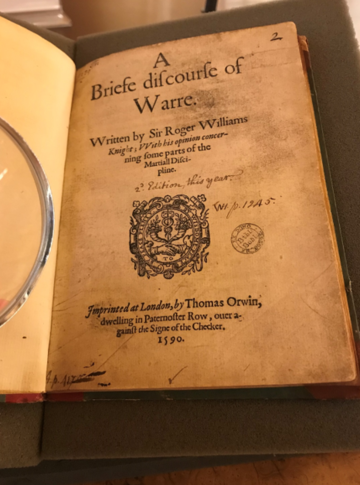

Early Modern History

Elliot Jordan - 'Spanish Blades': English Military Theory, the Spanish Threat and the Military Revolution, c.1558-1604'

Author’s photograph of Sir Roger Williams, A Briefe Discourse of Warre, in the Weston Library.

Williams’ military experience included nearly five years with the elite tercio regiments of the Spanish Army of Flanders before reverting to English service in the Low Countries, France and in England preparing to face the Armada in 1588. His Briefe Discourse went through three editions in 1590 and stridently advocated English military modernisation on the Spanish model. Williams, along with his fellow military reformers, likely inspired Shakespeare’s pedantic but skilled ‘Captain Fluellen’ in Henry V.

‘Sometime she driveth ore a Souldiers necke, and then dreames he of cutting Forraine throats, of Breaches, Ambuscados, Spanish Blades: of Healths five Fadome deepe, and then anon drums in his eares, at which he starts and wakes; and being thus frighted, sweares a prayer or two and sleepes againe…’

-Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet, Act I Scene iv.

In the second half of the sixteenth century, England’s self-styled professional soldiers were acutely aware that they were living through a period of ‘military revolution’ in the European art of war. The development of new weapons and tactics, fortification and military organisation spurred the replacement of the medieval host with the pike-and-shot-wielding regiment, and the individualistic, chivalric noble knight with the technically proficient and obedient gunpowder infantryman. Reacting to these changes, English military theorists began formulating, writing, and printing dedicated handbooks to teach aspiring infantry officers or young gentlemen ‘newe policies and practises of the greatest Souldiours in Christiendome, in these our present dayes’, fascinating sources on the art of Renaissance war and powerful rhetorical evocations of emerging martial and national cultures.

These men were spurred to action not merely by an infatuation with Renaissance military science, but also an awareness that England lagged behind continental military innovation at a time of serious national danger. This thesis has explored how their drive for military reform, whether in printed military textbooks, the new Trained Bands militia force or the patronage circles of Elizabeth’s leading commanders was driven by the impending threat posed by the Spanish Empire, the superpower of the sixteenth century. England’s quiet support of the Dutch Protestant rebels in the Spanish Netherlands from 1567 produced a generation of volunteer ‘crusaders’ advocating a renewal of martial virtues to combat Catholic Spain, while the eventual outbreak of ‘hot war’ in 1585 raised the spectre of Spanish invasion. In this religiously charged atmosphere, English military reform was driven by terror of Spain’s infamous tercio regiments, who in the minds of English soldiers and polemicists alike joined the Inquisition, the conquistadores and Philip II himself as ‘the Pope’s mynions; Spaniardes’, as one English military theorist called them.

Yet this thesis has found that, with their twin aims of military modernisation and national defence, English military writers both feared and admired Philip’s infantry regiments, unabashedly holding the tercios up as ‘the best soldiers of this day in Christendom’- as the Earl of Leicester apprehensively described them as invasion approached. To Elizabethan soldiers, ‘the Spanish discipline’ exemplified modern warfare, in their tactical formations ‘framed of expert and resolute men’ and in their creation of a professional veteran army, ‘old Regiments, where their souldiers be experimented, trustie and careful’. Paradoxically, it was thus with reference to England’s feared and loathed enemies that men like Sir Roger Williams, the premier English military theorist, advocated the development of a modern, professionalised English army to emulate the Spanish Army of Flanders, a force in which he himself had served and knew first-hand to be a ‘universitie continuallie in exercises’. In this combination of fear and admiration of the Spanish threat, Elizabethan military theory demonstrates the fascinating interplay of early modern military history with better-known themes of geopolitics, culture, and religion, and is an immensely rich source body on the Elizabethan military mindset as well as Renaissance ‘Arte and Science Militarie’.

Modern British History

Alice Reffin - 'Drawing the Empire or the Nation? Imagining the Irish Free State in the Posters of the Empire Marketing Board'

Seán Keating, Irish Free State Bacon, 1929, 100 x 151 cm (National Library of Ireland, Dublin, EMB/7)

Between 1926 and 1930, three Irish artists produced nine posters advertising the newly-formed Irish Free State. These posters, designed to promote Irish produce, were among the first to reimagine Ireland as a productive and peaceful nation, after a decade of revolutionary struggle. Yet it was not the Irish government, but the British, who commissioned the images – they were the work of the Empire Marketing Board, a seven-year project to ‘sell Empire’ to the British consumer, disbanded with the introduction of imperial preference in 1933. Within this peculiar epoch of British imperial history, the portrayal of the Free State is perhaps the most intriguing.

Despite the Irish Free State’s economic dependency on Britain, the Free State government was eager to retain symbolic distinctiveness in the EMB’s marketing and thus sought to effect agency over the decisions of the Board. Advertisements were sent to Dublin for approval, which was not always freely given: in November 1926, President Cosgrave declared that the appearance of the EMB’s slogan – ‘Ask – Is It British?’ – on an advertisement for Irish goods was ‘very objectionable’; the EMB reprinted the advertisement without it.

The attitudes of the Northern Irish Government to the work of the EMB remain unclear. Initially, the Board attempted to promote the island of Ireland as a harmonious community – a July 1927 advertisement promoted ‘food which comes from the green fields of Ireland’ – but this was quickly discarded with in favour of selling one Ireland at a time: a 1929 advertisement for ‘Irish Free State Dairy Produce’ hid the six counties under text. Thus, where possible, tensions surrounding partition were averted by conveniently obscuring the irrelevant state; in this way interpreting the imagined geographies of Ireland was left to the discretion of the viewer.

Most significantly, the Board accommodated the Irish Free State’s request that it employ Irish artists. Almost all posters produced for the EMB were designed by British artists but three Irish artists – Paul Henry, Seán Keating, and Margaret Clarke – were commissioned to create posters advertising the Free State, substantially influencing how it was imagined.

However, the work of Irish artists for the Board was also subject to censorship by the Irish government. A preview of Paul Henry’s poster, ‘Dairying in the Irish Free State’, received a negative reaction – the Irish Times complained that it portrayed the Free State as ‘the Cinderella of the British Dominions’ – and the poster was never displayed. Preferred by the Government were three posters by Keating that maintained an authentically Irish quality without appearing ‘backward’ but were critiqued as ‘by no means true to life’: for the posters of the EMB, the Irish Free State favoured an imagined modernity over the parochial reality.

The EMB’s decision to commission Seán Keating, and Keating’s acceptance, is the most intriguing aspect of the EMB’s portrayal of the Free State – Keating was a political painter determined to draw into existence an Irish post-colonial identity. Famous for imbuing his paintings with hidden meanings, as in his 1924 ‘An Allegory’, is it possible that his EMB posters are actually a critique of Ireland’s continued links to the British Empire? For advertisements of agricultural efficiency, a surprising number of figures are idle – a ploy Keating returned to in a mid-1930s series on Aran Island fishermen. Another Keating trick was to ‘hide’ political figures within non-political images, most famously ‘The Tipperary Hurler’ is actually the likeness of an IRA branch leader. Thus, a pig farmer in the background of ‘Irish Free State Bacon’ may actually be an anti-Treaty Irregular – his dress and posture certainly imply this. No sources survive to confirm these suppositions and historians must be cautious of imposing their own interpretation onto the subjectivities of historical actors, nevertheless the intentionality of Keating as an artist is evident.

Dulanty’s insistence that the EMB employ Irish artists resulted in a projection of the Irish Free State that was aspirational, authentic, and subversive. Both the employment of such artists and their pictorial challenge to the EMB’s colonial agenda embody the complexities of the relationship between British and Irish identity in the first decade after Irish independence.

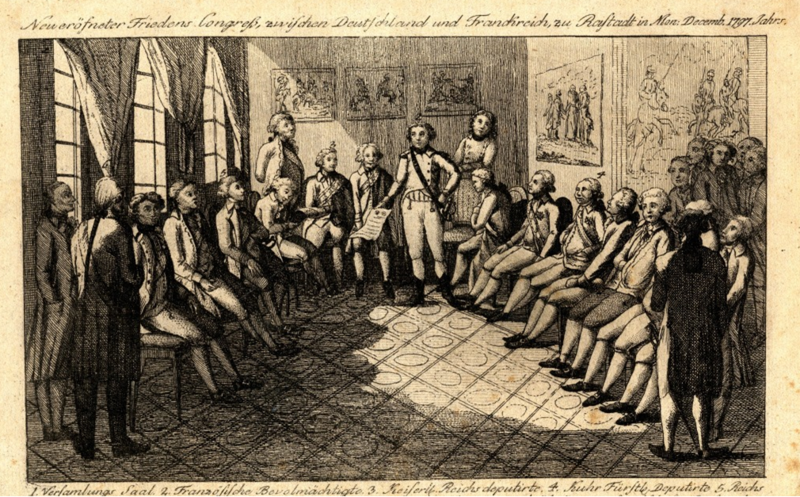

British and European History, 1700-1850

Harrison Goohs - 'German Freedom in a Revolutionary Epoch: The Congress of Rastatt (1797-1799) and End of an Empire'

The failed Second Congress of Rastatt (1797-1799) is an understudied episode in histories of both the French Revolution and of the Holy Roman Empire. Yet it is especially enlightening in light of a renewed interest in studies of the post-Westphalian Central Europe. Over 500 diplomats converged on Schloss Rastatt, representing every corporate class and imperial Estate, to influence the course of peace negotiations following France’s victory in the War of the First Coalition.

The debates at Rastatt centered around the question of territorial reorganization: German secular princes had lost land to Republican France, but as members of noble families in the Empire, they expected territorial compensation. Ultimately, they would preserve their dynasties and wealth, but at the expense of coequal members of the Empire. Specifically, the princes were awarded the riches and properties of the ecclesiastical Estates, Imperial Cities, and Imperial Knights.

But why was it determined that a prince from Pfalz could claim Church land in Bavaria? Passionate critics and defenders of the compensation plan went to the public literary sphere to voice their arguments—most often anonymously.

By examining these numerous publications—as well as diplomatic correspondences from the Congress in the French, German, and Austrian archives—I determined how authors viewed the Empire and how they legitimized their respective positions. Arguments for and against territorial reshuffling were grounded in attachment to both hallowed imperial law and a conservative Enlightenment project that cherished “German freedom.”

In one common metaphor, the Empire is cast as a building in need of repairs, but in another it is cast as an organism suffering from disease. And just as the building should not be demolished, the whole organism should not “be destroyed”; rather, the “diseased parts” should be excised or restored. Whether one argued in favor of the princes or in favor of the Church, the “diseased parts” were deemed as unenlightened and contrary to imperial law. Critics of the Church called it irrational and contrary to the principles of good governance; critics of the princes, meanwhile, called them materialistic, greedy, and antithetical to the greater interests of an enlightened “German Nation.”

My research reveals that arguments which had currency in the Empire overwhelmingly remained within traditional lines, viewing the Empire and its hierarchical nature as fundamental. But simultaneously, they were not anti-Enlightenment; instead advocating a conservative enlightened position which favored philosopher kings over republicanism. Except for a tiny radical minority, German intellectuals writing about future visions of Germany rejected republicanism. That notion prevented the implementation of necessary reforms at a moment of crisis, which ultimately precipitated the Empire’s demise in the Age of Revolutions.

Women's, Gender, and Queer History

Rosa Pouakouyou - 'Carving out space in the women’s movement: Northern Ireland and Spare Rib Magazine, 1980-85'

Historical scholarship has often excluded or reduced the role of women in narratives of both conflict and social movements that occur during a conflict. Whilst scholarship of the Troubles has increasingly acknowledged Northern Irish women, not just by placing women into the Troubles, but actively examining the various roles they played, less has been said about the Northern Irish women’s movement, both within Northern Irish women’s history and the history of the Troubles itself.

This dissertation had three main threads of discussion. First, it explored current conceptions of Northern Irish feminism and examined the ways in which feminism was influenced by and separate from the Troubles during the growth of feminist networks in the early 1980s. It sought to examine how Northern Irish feminists established an identity outside the confines of the Troubles, and how it was able to operate successfully without forming a unified movement. Secondly, it sought to debunk the notion, often perpetuated in scholarship of the wider women’s movement in Great Britain, that Northern Irish feminism was stunted or insular, and emphasised how the Northern Irish women’s movement engaged in multi-faceted, nuanced, and out-ward looking feminist activities. Finally, it examined how the Troubles allowed for the growth of exclusionary feminist strands whose foci was determined by ethno-nationalist identities particular to the Northern Irish context.

Using Spare Rib magazine as its primary source base, this dissertation sought to examine Great Britain’s most popular feminist magazine to explore the ways in which different Northern Irish feminists used print to advance the development of their particular ideologies and activities. Far from a unified group, this dissertation examined how different Northern Irish women and feminists (often not necessarily considered one and the same) leveraged Spare Rib as a tool through which they could place themselves and their causes, being both women and from Northern Ireland, into the national and international women’s movement.

Northern Irish women engaged with the broader women’s movement via Spare Rib, for example by openly critiquing the magazine’s position and understanding of the Troubles or, for Republican feminists (a particular ideological strand of Northern Irish feminism), by using the magazine as a means through which they could attempt to align their position with other women engaged in ‘anti-colonial’ struggle. By investigating Spare Rib this dissertation sought to demonstrate not only the existence of a fruitful Northern Irish women’s movement, but the diversity of that movement, its ability to challenge entrenched gender norms and advance opportunities for self-determination, and the particular role the Troubles played in shaping its development.

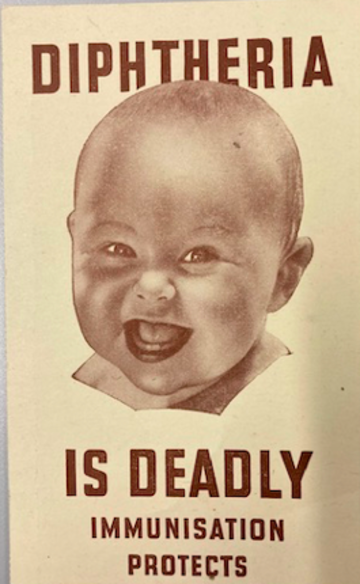

History of Science, Medicine, and Technology (MSc)

Antony Hollingworth - 'The introduction of a diphtheria immunisation programme during a time of war'

Wartime poster for immunisation

Diphtheria is a preventable life-threatening infection. In 1963 it was estimated that a General Practitioner (GP) would see one case of diphtheria every 400 years of practice[1] and in 2020 there were no toxigenic cases reported in the United Kingdom (UK).[2] However, the situation was very different before the start of the Second World War when the annual incidence of the disease was approximately 60,000 cases, 3000 of which would prove fatal.[3] Most of these deaths occurred in children; until the Second World War, diphtheria was the commonest cause of childhood death in the UK.[4] A vaccine, developed in the UK, had been available from 1921, the impact of which, in several other countries, had reduced infection rates considerably while remaining unchanged in the UK.[5] The aims of the dissertation are to improve the understanding of why, in the twenty years prior to the Second World War, take-up in the UK of diphtheria vaccine was relatively poor, challenging the conventional explanations for why, during the Second World War take-up improved and arguing that immunisation coverage during that period never reached a sufficient level to provide ‘herd immunity’.[6]

Policy prioritisation within the Ministry of Health (established 1919) in the inter-war period was problematic due to a rapid turnover of Ministers of Health (there were six within its first five years and a total of fifteen Ministers of whom only five were in post for two years or more). The interwar period saw many other chronic health problems competing for the attentions and limited finances of British public health officials. Some in the public health profession were distrustful of immunisation, with many MOHs preferring to concentrate on identifying carriers and confining patients to isolation hospitals. Public health doctors favoured the continuance of expensive institutional solutions to the infection and paid less attention to preventive medicine. The previously cautious attitudes to smallpox vaccination and the associated Anti-vaccination League activity were undoubtedly further factors explaining official reluctance to both immunising and making immunisation compulsory. Diphtheria was a mainly urban disease and an overall gradual fall in the deaths from all childhood infections may have influenced diphtheria’s lack of prioritisation.

The problems created by war, especially the threat of aerial bombing, evacuation of urban children (potential vectors) and associated fears of a widespread epidemics ultimately resulted in a change of policy with free prophylactics being provided to Local Authorities. The Ministry’s scheme was not applied on a large scale until 1941-42. The Ministry together with the CCHE and the MOI ran spirited publicity campaigns, however, surveys conducted during the war suggested they were not as successful at influencing uptake as anticipated. It became compulsory for those joining the services but the Ministry stopped short of making immunisation compulsory. In all, 262,000 notified cases of diphtheria were recorded in Britain during the Second World War of which 12,000 were fatal perhaps if the Ministry had heeded calls for compulsory immunisation and released the resources required earlier, that outcome could have been very different.

Using official material from the National Archives, supplemented by archives held at the Wellcome Library, contemporary local Medical Officer of Health reports and newspaper reports, this thesis aimed to provide a sounder understanding of the slow progress of diphtheria immunisation in Britain between 1920 and the end of the Second World War.

[1] JM Last, ‘The Iceberg ‘Completing the clinical picture’ in General Practice’, Lancet, (1963), p.30.

[2] Public Health England, Diphtheria in England 2020 Health Protection Report 7/15 (London, 2021), PHE Gateway number GOV-7997, p. 5.

[3] Ibid, p.3.

[4] Ministry of Health (hereafter MoH), Annual Report 1938-39 (London HMSO, 1939), Command Document (hereafter Cmd) 6089, pp. 24,232.

[5] Jane Lewis, ‘The Prevention of Diphtheria in Canada and Britain 1914-1945’, Journal of Social History, 1/20 (1986), p.163.

[6] Herd Immunity is a form of indirect protection that applies to contagious diseases. It occurs when a sufficient percentage of the population has become immune to said infection whether through previous infection or immunisation.