David Bowie and 'The Spectator'

I should start with an admission: I can hardly claim to be a David Bowie fan. Nor have I followed his career at all closely. However, when I was approached out of the blue by BBC music correspondent Mark Savage and asked whether I would be willing to do a short interview about a musical on the theme of ‘The Spectator’ which Bowie had been working on in the final year of his life, I was sufficiently intrigued to say yes. Teaching a Further Subject on London in the long eighteenth century, ‘The Metropolitan Crucible’, and having thought about The Spectator and its influence over many years now, I was curious to know why The Spectator, and what Bowie had in mind. We will come back to this shortly.

That Bowie had been working on this project was discovered when, after his death, archivists entered his New York City office to catalogue his belongings. A series of Post-IT notes were found where he had left them, fixed to the walls, on which he had made various, admittedly very brief notes – often no more than dates and names – relating to eighteenth-century London, while a spiral-bound A5 notebook contained some notes which he had made on the first 33 articles of the famous periodical The Spectator (1711-12). These materials can now be viewed on permanent display at the David Bowie Centre at the V&A East Storehouse in the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park in London, the new home of the David Bowie Archive.

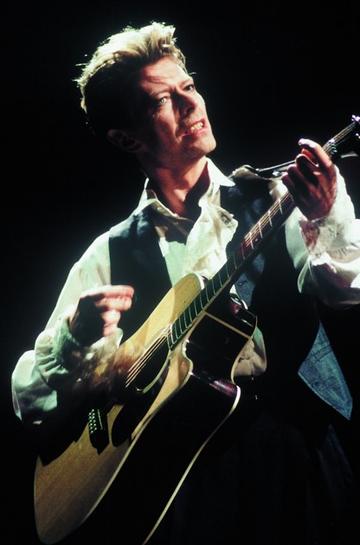

Bowie’s keen interest in musical theatre is well known. In 2002 he told the BBC’s John Wilson that he had wanted to write for the theatre from the very start of his career. But why early eighteenth-century London and why ‘The Spectator’?

The answer to the first of these questions seems to be fairly straightforward. London of the early eighteenth century was the wonder city of the age, a place which by turns thrilled and shocked contemporaries. This was a consequence in the first place of its size – its population by 1700 was already just over half a million – and it dwarfed all other British and all but a handful of mainland European towns and cities. In 1700 only Paris was of similar size; the population of Amsterdam was under half that of London.

Equally striking was its rapid redevelopment and continued expansion following the destruction wrought by the Great Fire of London of 1666. Defining what was London and where its boundaries lay defied simple answers; fashionable Westminster was taking shape in the west, and villages on all sides were sucked into its widening maw. Yet if London was increasingly distinguished by a process of disaggregation, it was also its very diversities which struck contemporaries.

London was the site of myriad, stark contrasts, between dizzying wealth and grinding poverty, the polite and impolite, the industrious and the idle (rich as well as, if not more than, poor). Supported by the continued development of the London ‘Season’ after 1689 and the unexampled concentration of potential patrons from the landed classes as well as the plutocratic elite, the financiers and the merchants, it was a crucible of cultural innovation, further fuelled by a seemingly unlimited appetite for novelty. It was a place of spectacle – whether this be the grisly hangings and so-called Tyburn procession of the condemned which wound its way from Newgate to Tyburn, the drawing of the state lottery at the Guildhall, the tension-filled drama of the court room at the Old Bailey and Westminster Hall, the elaborate staging of Italian opera, the Swiss impresario Jacob Heidegger’s masquerade balls, fairs with their popular entertainments and shows, or various popular rituals, such as the Pope Burning parades of 5 November.

The selling and buying of sex were pervasive and open, if periodically subject to unavailing efforts to contain or suppress this. One of Bowie’s notes reads, ‘Many sex scenes’! Sex of all kinds could be had, usually for a price, although this of course also spoke to the acute fragility and insecurity of the lives of the many young women who came to the capital in search of employment usually as domestic servants. Behind one person’s gratification was another’s exploitation, even if the fantasy existed of defying the odds of disease and degradation which were the lot of most women selling sex to men. Bowie had evidently read Vic Gatrell’s highly readable book The First Bohemians: Life and Art in London’s Golden Age, in which Gatrell presents Covent Garden and its environs as a sort of proto-Bohemia, a place in which the eager pursuit of pleasure – in many varied guises - the visual arts and artists, writers, actors and the criminal existed tightly alongside one another. Gaming Houses were concentrated in and around Covent Garden; it boasted large numbers of courtesans and whores. The piazza along with Lincoln’s Inn Fields were the cruising grounds for those in search of homosexual sex. This was a world in which high and low met in promiscuous propinquity.

It was the ‘low’ which seems to have drawn much of Bowie’s attention. Many of the notes concern the thief taker Jonathan Wild and the master of prison escape, Jack Sheppard. Both became popular celebrities in early eighteenth London, lionized in popular print for their exploits and their brazen disregard of authority and in Sheppard’s case attempts to confine him. Peter Linebaugh in his richly detailed and highly stimulating book The London Hanged argues that Sheppard’s life encapsulated and symbolised resistance to the structures of confinement through which the propertied and the authorities sought in this period to discipline and literally re-make the lower orders as a compliant working class. His pursuit of freedom spoke to their aspirations, desires, and deepest political instincts.

However, this was a London which largely defied the many and increasing efforts to contain its disorderly energies, which, in any case, came from above as well as below. Another of Bowie’s notes reads, ‘Mohocks attack central figure’. Named after Iroquois chiefs who had visited London in 1711, the Mohocks were basically part of a depressingly long catalogue of upper-class young men who, fired by the consumption of copious amounts of alcohol, have felt the need to prove their ‘rakish’ credentials at the expense of others. On this occasion, they did so by attacking, often very brutally, women and elderly watchmen on the capital’s streets. The ‘Mohocks’ were probably an invention of the burgeoning print media of the time, and the very term suggests a coherence and identity which was absent. Nevertheless, the attacks were real, as were the profound fears which they induced. Several of the perpetrators were apprehended, and the court records mean that we can identify several of them. Sir Mark Cole and three of his friends were tried in 1712 at the Old Bailey for riot and assault. Found guilty, each was fined the risible sum of 3 shillings and four pence. Well might many believe that justice changed its spots according to the status of those on trial, whatever the defenders of the rule of law might protest. Cole and his friends’, armed with clubs weighted with lead at both ends, had (merely) beaten up 13 men in a gaming house, abused a watchman, slit two people’s noses – a speciality of these types – sliced open a woman’s arm, rolled another woman in a barrel down Snow Hill, sat on other women’s heads and, oh yes, overturned several sedan chairs and coaches. The Mohocks were as much a product of London in this period as, say, the theatre, the opera, or, indeed, the coffee houses which have been portrayed by some historians, almost certainly in a rather distorted fashion, as major sites of enlightenment intellectual exchange and sociability. In truth, coffee house ‘culture’ – that is if we can talk in such terms – was much more diverse and rather less elevated in tone than this conveys, a reality comically captured in Ned Ward’s joyful and lexically hyper-inventive ‘inside view’ of London in the early eighteenth century, The London Spy (1709). One of Bowie’s notes simply reads ‘Coffee Houses’.

Beyond this, it was perhaps the very brazenness of London of this period, or more precisely its chroniclers, which drew Bowie to it. This is a major theme of Gatrell’s book, which charts how much of the art which the London of this era produced did not shy away from portraying the darker sides of London society or the contradictions which it threw up. Or these artists’ judgements, where these even exist, are ambiguous. Much of the art of William Hogarth but also, and perhaps more obviously, Thomas Rowlandson, himself a prolific gambler, is of this sort. (Rowlandson is the real hero of Gatrell’s book, which features many of his drawings and pictures). Moreover, what might at first sight seem polite or respectable, on closer view reveals something entirely different. Appearances deceive, at least to the uninitiated.

The predatory and predatory sex lurked not in the shadows but in full illumination. This is not, of course, the full story or anything like. For out of this same world emerged an art scene of unexampled influence and quality, the tap roots of which were established by artists and engravers who came to the city from different parts of continental Europe, an apt reminder that London has always been a city of immigrants, whether from overseas or the rest of Britain. In the early eighteenth century, many of those from overseas were French Protestants, who brought with them the skills of silk manufacturing and settled in Spitalfields. The emergent financial world was liberally sprinkled with the entrepreneurial talents of those from the United Provinces and France. Another creative ingredient were significant numbers of Sephardic Jews. This was one reason why this bothersome financial world was loathed by Jonathan Swift and the Tories, then as now the party of ‘little England’, who saw it as parasitic and flourishing at the expense of a heavily taxed and over-stretched landed gentry. London was a major site of manufacturing and craft skills. As Linebaugh notes, Sheppard’s magic, the remarkable dexterity and manipulative genius he demonstrated in defying confinement, comprised the very aptitudes prized in a metropolis of skilled craftspeople.

However, what did Bowie glean from reading The Spectator? This on the face of things is more of a puzzle. For while the periodical was a phenomenal success, an instant hit no less, and exercised an astonishing influence on contemporaries across society throughout the eighteenth century through its many reprintings in collected editions and publications of other sorts, including educational ones, it had several purposes, none of which seem obviously relevant to Bowie and his project. For one thing, it was an antidote to the highly partisan politics of the period, antidote but also intervention therein. Its main authors, Joseph Addison and Richard Steele, were Whigs, and they launched the periodical at a moment in which the Tories under Robert Harley had gained power and were at the height of their popularity. Like their patrons, Addison and Steele were out of favour and place, and they had the time to undertake a new journalistic initiative. They had first collaborated on Steele’s The Tatler, an altogether different kind of publication. They may have declared an ‘exact neutrality’ in politics in The Spectator, an avoidance of news, and sought to promote moderation and accommodation between different interests – Whig and Tory, land and trade, Church of England and Dissenter - but it was a Whig consensus which they sought to write into being.

For another thing, their aims were avowedly morally reformist. They wrote to make religion and virtue fashionable, to replace the febrile and vacuous preoccupation with novelty and the present which defined contemporary news culture and partisan politics with more substantial matter. Hence the famous declaration in Essay 10 of the periodical by Addison: ‘It was said by Socrates that he brought Philosophy down from Heaven, to inhabit among Men; and I shall be ambitious to have it said of me, that I have brought Philosophy out of the Closets and Libraries, Schools and Colleges, to dwell in Clubs and Assemblies, at Tea-Tables, and in Coffee-Houses.’ The ambition was to rescue society from the ‘desperate state of Vice and Folly into which the Age is fallen.’ Wit and humour were to be the tools with which to achieve these goals; even their political foes acknowledged that they had wit and invention in abundance. Women were, as implied by the quotation given above, central to this project. But what Addison and Steele gave with one hand in this context, in terms of acknowledging the role of women as civilizing agents and facilitators of a reformed sociability, they took away with another. As recent scholars have emphasized, both writers insisted very clearly on the primacy of domestic roles for women and viewed their destinies firmly in terms of marriage.

Bowie’s notes offer little guidance about what he gained from his reading of The Spectator. He awarded the essays marks out of 10, seemingly on the basis of how far these interested him or he could concur with the views which they propounded. My sense is that, rather like the Whig historian T. B. Macaulay, and many others besides, it was the incidental details about London life contained in the periodical which mainly drew his interest. The essays offered him a unique window on the London of this period. He read, for example, essays 9 and 24, which were both about the myriad clubs which laced together London society, or rather that of men, and which were such a prominent feature of the eighteenth century. Issue no. 24 comprised a series of letters on the theme of clubs. One of these referred to a Mr Clinch of Barnet, who used his voice to imitate instruments and various characters, including a pack of fox hounds and hunters. Clinch performed in taverns and spas around London, part of an only partially visible world of commercial entertainment and leisure which flourished at all levels of society. The pleasure gardens of Vauxhall and Ranelagh are known well enough, but their many epigones have slipped from view.

Other essays commonly concerned personal conduct. One of these which Bowie noted, maybe a bit strangely, as having the potential to make a good subplot, was a fictional tale of two sisters, Laetitia and Daphne. The former was distinguished by her good looks and vapidity of her conversation; armed with arresting looks she had never needed to develop the art of conversation. Daphne by contrast had plain looks but good sense and agreeable conversation. The tale concerns a young man who all too predictably falls in love with Laetitia on espying her at the theatre. He visits her, but she treats him with predictable disdain. He falls into conversation with Daphne and you can no doubt guess what follows. He falls in love with Daphne and eventually asks her father for her hand in marriage. One might well wonder where Daphne’s wishes feature in all this, but that emphatically is not the point. The moral of the story lies elsewhere – ‘[the] true art of assisting beauty consists of embellishing the whole person by proper ornaments of virtuous and commendable qualities’. The essay also offers some telling side-swipes at the contemporary business of beautification, and the ‘quacks and pretenders’ which populated that scene and whose remedies and ointments featured in many a contemporary newspaper advertisement. Perhaps it was the seeming familiarity of London in this period which also attracted Bowie. Many have written of London in the eighteenth century as if it was, in some sense, the forcing house of the modern world. This obviously carries all the dangers of what used to be called ‘Whig history’. Despite this, however, it has proved a seemingly irresistible temptation to many an author of recent trade books on the period and, indeed, a good few academic publications. It is the differences which are more salient and demanding of our understanding.

And for the title - ‘The Spectator’: this is pure speculation, but my suspicion is that it was the character of ‘Mr Spectator’ which may in this context have inspired Bowie. Addison’s ‘Mr Spectator’ is the silent observer of London and its dramas and scenes, one who offers his words only on the pages of his periodical – a detached but curious viewer of all that they witness. Perhaps Bowie thought that a narrator of this type could link together the different and varied scenes and plots which would make up his musical. It’s a beguiling notion and one for which there is ample precedent. One final puzzle: why no obvious reference in any of the material to John Gay’s English ballad opera ‘The Beggar’s Opera’ which ran for a then record 62 nights at John Rich’s Lincoln’s Inn Theatre in 1728 and which was the subject of a large number of paintings by Hogarth.

Commercially the most successful production of the eighteenth century, Rich used his profits to build the Covent Garden Theatre. In this pastiche of contemporary Italian opera, Gay used the criminal underworld to offer a delightfully knowing and subversive commentary on the rule of Sir Robert Walpole and the tightly controlled, narrow political system which he constructed. Perhaps the project just hadn’t advanced very far, or perhaps it was a contemporary model which he consciously resisted. We will of course never see Bowie ‘The Spectator’ on the London stage or Broadway. Maybe, however, someone else will take up the idea; it was a good one.