Experiences of Race, Class and Archival Survival for Black Women in Georgian Britain

My Further Subject therefore served not just as a requirement for my degree but as a project of reconstruction, utilising a range of primary sources to uncover the stories of Black women and their presence on British soil.

Alicia Kaseya is a final year undergraduate who is studying History at Worcester College. She is from Wolverhampton, where she was educated at non-selective state schools. In Year 12, she attended the Oxford UNIQ summer school and completed the Opportunity Oxford residential prior to starting her degree. In this blog inspired by her Further Subject, she explores how race and class shaped Black women’s lives in eighteenth-century Britain, and how these differences influenced their livelihoods and representation in the archive.

When I was in Year 13, I read Black and British: A Forgotten History by David Olusoga. I was struck by the potent way in which Olusoga aimed to create a chronology of Black Britain, and the pertinence of this history to current affairs. Whilst reading this book, I was fascinated by the ambiguity which characterised the existence of Black people in Georgian Britain. Discourses on slavery and the Empire which were reverberating through the metropole affected not only how Black people in Britain were viewed, but also their lived experience and how they are remembered. Thus, when the option to take the Further Subject Black Women and British Society, 1750-c.1865 for Finals presented itself, I jumped at the opportunity and submerged myself into the extensive historiographical debate on Black Georgians.

In uncovering the experiences of Black Georgians, the politics of the archive—namely the recording and storage of the body of materials that historians use to centre their discussions about Black Britain—presents researchers with much difficulty. The archive has aided the erasure and forgetting of Black Georgians as it disregards that, fundamentally, women of African descent in Britain were people with unique experiences. In abetting this process of forgetting, the archive primarily demonstrates how Black women were stripped of their identities and forced to adopt identities which were ascribed unto them by colonial authorities and individuals (Fuentes, 2020). My Further Subject therefore served not just as a requirement for my degree but as a project of reconstruction, utilising a range of primary sources to uncover the stories of Black women and their presence on British soil.

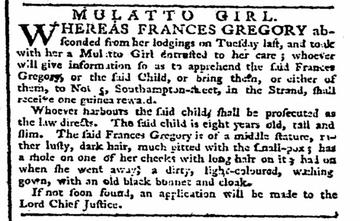

Figure 1: 'MULATTO GIRL', General Advertiser and Morning Intelligencer, 4 April 1779

Race often intersected with class in demarcating the social and economic boundaries for Black Georgian women. During this period, a vast number of Black women in Britain occupied roles within households, working as laundrymaids, seamstresses, and children’s nurses. These positions demonstrated the extent of the Black population who were members of the labouring poor classes, often subjected to harsh conditions and low wages, if any at all. Records of runaway slave advertisements allow for a deeper insight into the aspects and dynamics which shaped how Black women lived in domestic settings. For example, in April 1779, the General Advertiser and Morning Intelligencer reported the escape of Frances Gregory, a Black woman, who fled with a “Mulatto girl entrusted into her care.” While the advertisement does not provide Frances’s perspective, it offers a hint of how domestic service could allow Black women to form alternative familial bonds. By fleeing with the child, Frances may have exercised a maternal or protective role, which suggests that even within the constraints of servitude, Black women could create personal connections that disrupted the dehumanising structures of their oppression. This potential for agency aligns with Myers’s observations on North American slavery, where Black women often assumed “auntie” roles or cared for unrelated children when familial ties were disrupted by forced migrations (Myers, 1996). Although the British context differed, Frances’s case suggests the possibility of a parallel phenomenon.

While Frances’s experience reveals the emotional and material precarity of Black domestic servants, other lives offer a contrasting perspective. Even within domestic service, the experiences of Black women were far from monolithic, as illustrated by the life of Fanny Coker, who highlights how certain conditions such as freedom, education, and strategic relationships could shape a markedly different trajectory. Born enslaved on the Mountravers sugar plantation in Nevis, owned by the Pinney family, Fanny was manumitted in September 1778. Following her emancipation, she received an education and trained as a seamstress, which laid the foundation for her future as a wage-earning servant. In 1783, Fanny left Nevis with the Pinney family and worked for nearly four decades as a servant in their home in Bristol. Her position as Mrs Pinney’s lady’s maid afforded her the status of the highest-ranking female servant, and this intimate role granted Fanny a degree of autonomy and access to privileges. For instance, she was entrusted with overseeing the Pinney family’s country home, Racedown in Dorset, a responsibility that emphasised her independence within the household hierarchy (Eiclemann, 2020).

Fanny also skilfully leveraged her proximity to the Pinney family to maintain ties to her homeland and improve her financial position. She used the Pinneys’ extensive network of friends, business contacts, and visitors to stay informed about Nevis and send money back to her family. Through her unique circumstances, Fanny was able to exert limited agency over her life, demonstrating how freedom, and social positioning could enable formerly enslaved Black women to navigate systems of oppression with relative independence. Nonetheless, Fanny Coker’s successes were profoundly limited by the fact that she was a Black woman, as her relative stability was rooted in her proximity to white patronage. Her position and modest independence depended heavily on the “great tenderness” of the Pinney family, highlighting how her lowly status was mitigated, but never erased. Eiclemann has also noted that the information about Fanny comes solely from official documents and records, all of which are filtered through her status as a servant, as she left no written accounts of her own (Eiclemann, 2020). Fanny’s life therefore remained confined to service, a reality that reveals the structural barriers Black women faced.

Figure 2: Portrait of Dido Elizabeth Belle and Lady Elizabeth Murray, 1778

These nuances also extended to Black women in elite settings, as seen in the case of Dido Elizabeth Belle. Dido was the great-niece of aristocrats Lord and Lady Mansfield, famously represented in the portrait with her cousin Lady Elizabeth Murray. Whilst Dido’s position may have provided her with certain social comforts, her status as a Black woman subjected her to a significant degree of erasure in the assessment of her lived experience. In the portrait Dido Elizabeth Belle and Lady Elizabeth Murray, racialised distinctions are apparent. Dido is depicted wearing what has been described as an “orientalising or masquerading costume,” in contrast to Lady Elizabeth’s more conventional attire for a woman of their social standing (Germann, 2021).

What is particularly telling, however, is the treatment of this portrait within the archives. Dido’s presence, and any recognition of her as a Black member of an aristocratic household, was effectively erased from public memory. Germann notes that although the portrait was framed, it was relegated to a storage room, possibly suggesting an attempt by the portrait’s proprietors to keep it out of view (Germann, 2021). Furthermore, a 1904 description of the painting from a Kenwood inventory does not even name Dido or acknowledge her status. Instead, she is referred to dismissively as a “negress attendant,” a denial of her position within the family and a striking example of archival violence. Despite the rank and visibility her unique position might suggest, Dido’s life was subjected to the same mechanisms of erasure that marginalised Black women of all social standings. Ultimately, this illustrates that Black women, regardless of their social rank, faced systemic silencing, with their precarious positions reinforced by the very archives that might have recorded their lived experience.

Through figures like Frances Gregory, Fanny Coker, and Dido Elizabeth Belle, we see how Black women in eighteenth-century Britain navigated intersecting hierarchies of race, class, and gender that both constrained and defined them. Their fragmented traces remind us that the archive is not a neutral space, but one shaped by the same structures of power that determined whose stories were worth remembering.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Dido Elizabeth Belle and Lady Elizabeth Murray. Accessed at Jennifer Germann, "Other Women Were Present": Seeing Black Women in Georgian London, Eighteenth-Century Studies, 54/3 (2021), pp. 535-553

‘MULATTO GIRL’ General Advertiser and Morning Intelligencer, 2 April 1779, Accessed at Runaway Slaves in Britain: bondage, freedom and race in the eighteenth century [https://www.runaways.gla.ac.uk/database/}

Secondary/Further Reading

Eiclemann, C., 'Within the Same Household: Fanny Coker' in Gretchen H. Gerzina (ed.), Britain’s Black Past (Liverpool, 2020), pp. 118-137

Fuentes, M., Dispossessed Lives: Enslaved Women, Violence and the Archive in the Urban British Caribbean (Philadelphia, PA, 2016)

Germann, J., "Other Women Were Present": Seeing Black Women in Georgian London, Eighteenth-Century Studies,54/3, (2021), pp. 535-553

Myers, N., Reconstructing the Black Past (Oxford and New York, NY, 1996)

Trouillot, M.R., Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of the Past (Boston, MA, 2015)