Medicine and history – a matter of degrees

When I came down from Merton in 1961, a history degree was simply a passport to your first job. Few graduates kept up an interest unless they intended to teach it. The Oxford Historian was decades in the future and (if my memory serves correctly) the History Faculty had little time for the departed. One might pick up a Faulkner or Follett occasionally, but the love of discovering history for oneself withered.

In my mid-twenties I chucked a promising career to read medicine, and on the wards and in the clinics I found that a history degree was a great foundation. I’ll explain why.

The first thing that a clinical medical student learns is how to take a history from a patient. (That word again!) You listen to evidence from a primary source, all the while sorting the chaff from the wheat and weighing and discounting prejudice and exaggeration. You allow for differences in a patient’s understanding, language and culture. As you listen, you form a theory (a diagnosis) which you test by deductive logic. That means performing a physical examination, ordering laboratory tests and consulting articles as well as your experience of similar cases. Then you summarize your findings for the notes.

Back at Merton my ‘special subject’ was John of Gaunt and the Peasant’s Revolt of 1381. For two years we made an intense study of the primary sources in their original language: Froissart’s Chronicles in mediaeval French; the Parliamentary Rolls in mediaeval Latin; monastic writers in vernacular Latin and sources like Piers Plowman in Middle English. Some were a nightmare to read and full of inaccurate dates, misplaced geography and wilful bias. The experience proved invaluable in sorting out patients’ histories.

There is also the aspect of committing oneself to a conclusion, which is essential to both a historian and a doctor. Later in life I became a histopathologist, a laboratory-based doctor specializing in the diagnosis of tissue samples at the microscopic level and dead bodies at the macroscopic level. My raison d’etre was to write reports that were reliable and, as far as possible, unequivocal.

The importance of the last point can be illustrated by the apocryphal tale of a hospital which advertised for a new pathologist. The advert stated that preference would be given to a one-armed applicant. When challenged, the answer was as follows. “We’re fed up with our present man. His reports always say, ‘On the one hand it might be X, but on the other hand it might be Y.’”

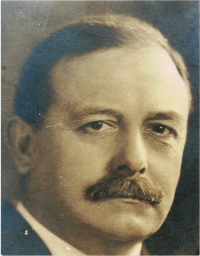

Dr Thomas J. Cochrane, 1866-1953

(Cochrane family collection)

The main block of the Union Medical School on Hatamen Street, old Peking, newly opened in 1906.

(Cochrane family collection)

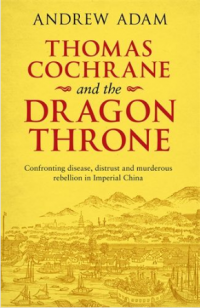

In retirement I found an ideal topic for my two muses of history and medicine. The result of four years of research, Thomas Cochrane and the Dragon Throne, will be published by SPCK this November. Cochrane was a young Scottish doctor and missionary who in 1897 arrived in Inner Mongolia, China’s most remote territory. There he encountered unbelievable difficulties and dangers. After three years of working single-handed in a mud-floored dispensary, he concluded that his efforts were a drop in the ocean of the population’s suffering and that a radical new approach was needed. He was gripped by the vision of building a western medical college and teaching hospital in Peking.

Next he was caught up in the horrors of the Boxer Uprising in which 30,000 converts and nearly 300 missionaries were slaughtered. He narrowly escaped with his family and undeterred returned to Peking in 1901 to treat beggars, lepers and opium addicts in converted mule stables. He worked in obscurity and poverty until he won allies in the Imperial Court by bringing a cholera epidemic under control. With the help of the Chief Eunuch (who became a patient) he gained the patronage of the dreaded Empress-Dowager Cixi.

In 1906 Cochrane founded the Union Medical College, China’s first college of western medicine. Today it still stands in Beijing, a prestigious academic and clinical centre, its missionary origins largely forgotten.

Thomas Cochrane was my step-grandfather, who died when I was fourteen. I was always intrigued by his adventures and how he succeeded in establishing China’s first institution of medical science in such a hostile environment. After inheriting his papers, the urge to delve into them was irresistible.

Cochrane’s story illustrates the struggle and victory of perseverance over adversity and of truth over falsehood. To me that is not just history; it is rattling good drama.

Andrew Adam

In 1897, Tom Cochrane, a young doctor, arrived with his bride in Inner Mongolia, China’s northernmost territory. Three years later, after labouring single-handedly in a mud-floored dispensary, he realized that his work was a drop in a sea of suffering. A radical new approach was needed. He was gripped by the vision of a Western medical college and teaching hospital in Peking. In 1900, the Boxer uprising broke out. Fanatics roamed the countryside crying, ‘Kill the foreigners! Kill them before breakfast!’ The Cochranes and their three little boys fled as thirty thousand Christians and hundreds of missionaries were butchered. Undeterred, Tom returned to Peking in 1901 to treat beggars and lepers in converted mule stables. After bringing a major cholera epidemic under control, he won allies at the imperial court. With the help of the chief eunuch, he gained the support of the dreaded Empress Dowager. In 1906, Cochrane established the Union Medical College in Peking, China’s first Western medical school. It still stands today, a prestigious academic centre, its missionary origins forgotten, but it is one of countless seeds planted by Christians in China.