Necromancy and Witchcraft – or Theft?

Dr Rowena Archer

Six hundred years ago, on Friday 29 September 1419 – Michaelmas Day – the dowager queen of England, Joan of Navarre, was arrested on the orders of her stepson, Henry V. Joan was at her manor of Havering in Essex; Henry V was on campaign in Normandy where he had been since 1417. According to the parliamentary record, Joan’s confessor, Friar Randolf, had accused her of ‘compassing the death and destruction of our lord the king in the most treasonable and horrible manner that could be devised’. Allegedly two domestic sorcerers had been aiding the queen to deal with the powers of darkness to bring about her evil aim. This is by any standards an astonishing episode, unique in the history of medieval queens.

Joan of Navarre vies with Richard I’s queen for the place of least known among the English queens although this ought not to be so, not least on account of her magnificent effigy in Canterbury cathedral which lies along side that of her second husband, Henry IV. She was born about 1368, the daughter of a king – Charles of Navarre. In the court of the newly crowned Valois king of France he was called ‘le mauvais’ mainly because but for the invention of the salic law which barred the royal succession passing either to or through a woman, he was France’s king. In 1386 Joan married John de Montford, duke of Brittany, a man of 47 who had already had two wives, both English. It is a measure of her importance that her father offered 120,000 livres of gold and 6,000 livres of rents as dowry, though this was never paid. The duke of Brittany, however, endowed her with extensive lands and property including the towns of Nantes and Guerrand. Neither Mary Plantagenet nor Joan Holland had given Duke John children but Duchess Joan produced nine children for her older husband. Five predeceased her. Ties between Brittany and England were ancient and in the late fourteenth century were close. Duke John had been raised in the court of Edward III and in the disputed succession to the duchy the English crown had sustained the Montfords and their claim.

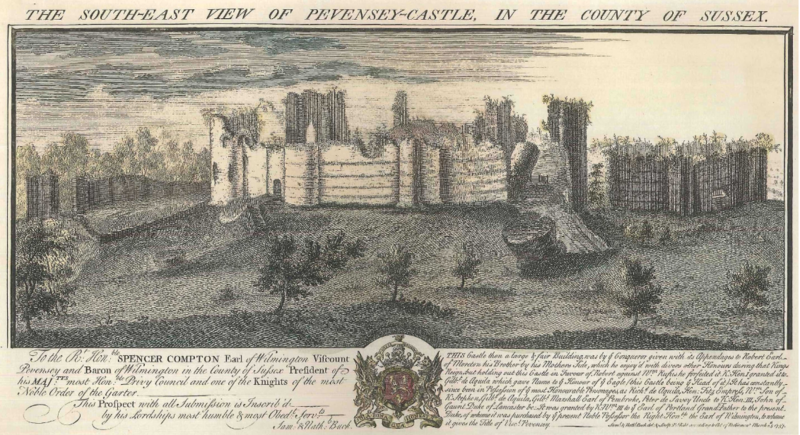

The South-East View of Pevensey-Castle, in the County of Sussex (1737). Joan was kept here durng her imprisionment.

Widowed in 1399, Joan became regent for the new duke John who was only ten but two years later she oversaw his inauguration as duke. Whether this was in anticipation of remarrying is unclear but it was Joan who sent a proctor to open negotiations for marriage to the usurping English king Henry IV whom she had already met. Joan’s determination to secure Henry is apparent from her seeking a papal dispensation to marry whom she pleased even if related to someone within the forbidden fourth degree of consanguinity. This was partly because during the Great Schism she recognised the Avignon pope while Henry having accepted the Roman pope would naturally be regarded as schismatic. The couple were married by proxy on 2 April 1402 and at Winchester on 7 February 1403. Joan was crowned on 26 February, a drawing of which event was made for the Beauchamp Pageant, a pictorial representation of the life of Richard Beauchamp, earl of Warwick (d.1439) who had fought as her champion in the tournament held to celebrate the coronation. The couple had no children and the marriage was not popular in England, France or Brittany. Henry IV hardly made matters better by increasing the usual royal dower from £4,500 to £6,500 p.a. Among the many rich manors she received were the castles of Bristol, Nottingham, Leeds and Hertford. Joan, however, made every effort to be a good stepmother. After Henry IV died Joan remained in England and there is much evidence of the great respect and esteem shown to her by Henry V who on more than one occasion called her ‘his dearest mother’. In 1414 he gave her special permission to reside in his royal castles, including Windsor. She was honoured with special Garter robes in 1416; a truce with the duke of Brittany was made in 1417 ‘at the prayer of Joan’; and in 1418 Henry gave special orders for her to receive and trade goods free of export and import duties. So what went wrong? A more unlikely candidate for necromancy against Henry V it would be hard to imagine.

The tomb of Joan of Navarre, buried with King Henry IV at Canterbury Cathedral

The most detailed biography of Joan remains that written by Agnes Strickland in 1840. Whilst broadly sympathetic Strickland considered avarice to be her besetting sin but she was quite clear about what was going on in the autumn of 1419. In his generally admiring 1992 biography of Henry V Christopher Allmand tucked a very brief summary of the story into a footnote. In his recent study of Henry V, highlighting the ‘conscience’ of the king, Malcolm Vale never mentioned her at all. Strickland, however, was forthright: ‘It was one of the dark features of the age, that the ruin and disgrace of a person against whom no tenable accusation could be brought might readily be effected by a charge of sorcery, which generally operated on the public mind as the cry of ‘mad dog’ does for the destruction of the devoted victims of the canine species’. Joan was never charged because there was no charge but she was rich and at the time of her arrest Henry V was poor – poor on account of the vast drain on his resources arising from war in France. She was placed under house arrest and stripped of her dower lands. She was confined in comfort at Leeds Castle (hardly the treatment of one allegedly seeking the death of its owner), and the profits of her lands were effectively stolen to replenish her step son’s war chest.

In July 1422, ‘doubting lest it should be a charge unto our conscience for to occupy forth longer [the dower of ‘our mother, queen Joan’…. the which charge we be advised no longer to bear on our ‘conscience’ Henry ordered his council, ‘as ye will appear before God for us in this case to restore the queen wholly of her dower’. He offered too a feeble compensation in the form of cloth of her choosing sufficient for five or six gowns. Horses for eleven chariots were assigned to enable her to leave her confinement and go to ‘whatsoever place within our realm that her list and whenever she list. Henry had acted in timely fashion for six weeks later he was dead.

Dr Rowena Archer

Fellow at Brasenose

Lecturer in Medieval History at Christ Church