Making History Personal

One evening recently I was talking on BBC Radio Lancashire about a young man from Blackburn called William Stirzaker. In 1850, William was caught stealing a coat, for which he was transported to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania) for seven years. The next day I got a message from a young woman called Lauren Stirzaker, who’d heard the broadcast and wondered if they were related. The name is not common. I sent her links to William on convict websites.

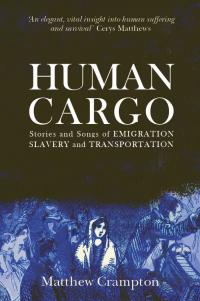

Two weeks later, I took my show Human Cargo to Blackburn. It’s an evening of words-and-folksong based on my book Human Cargo: stories & songs of emigration, slavery & transportation. (No, it’s not a bundle of laughs, in case you were wondering, but the show is often unexpectedly entertaining.) Human Cargo gives voice to migrants and exiles from past centuries, to cast light on today’s migrations.

Two of the main characters in the show are Sophia Clifton and Olive King, teenagers from a Brighton workhouse, who in 1839 were transported for 14 years for trying to steal clothing worth seven shillings. The official purpose behind such savagery unfolds over the evening.

Other characters we follow include a boy kidnapped from Aberdeen in 1743 and sold as an indentured servant in Virginia, a community from South Uist in the Western Isles, evicted during the Highland Clearances to Quebec – where they were dumped in late autumn, with no food, money or shelter - and the enslaved African Olaudah Equiano.

I weave in local stories wherever we perform. During the section on transportation, I talked of William Stirzaker and, seeing an immediate reaction from Row Four, I guessed his descendant Lauren was there. Indeed she was, with her father. I introduced them. Audiences love such moments when the history comes alive. But a greater co-incidence was yet to strike.

There’s a point in the show where I mention that much British wealth was derived from the particular horros of slavery – which still surprises some people – and that signs of the largesse surround us today. I talk of the UCL website Legacies of British Slave-ownership. ‘Type in any town and you can find out who benefitted locally from enslavement.’

In Blackburn this meant Joseph Fielden, the local MP between 1865 and 1869, who was compensated £13,500 for the loss of his slaves in Jamaica. (The fact that Abolition compensated slavers, not the enslaved, is still news to some people.) When I mentioned Fielden’s name, the audience got agitated. Hands pointed upwards. There on the wall was a plaque saying this very building – a community hall - was built by Joseph Fielden. ‘The Fielden’s Arms is next door’ someone shouted. I’d not planned this. As ever, people stir when history taps them on the shoulder.

Each night on tour I would say, ‘So I type in wherever we’re performing – to see how guilty the place is.’ (An old trick for raising anticipation, and competitiveness). ‘St Albans surprised me. Nothing. The town was clean. Unlike Welwyn or Hatfield nearby. Last night in Cardigan was more typical - one local slaveowner. And then I tried today’s city.’ At this point, one night, the audience tittered. We were in Bristol.

‘289 individuals, each significantly compensated for owning slaves. There’s nowhere like it outside London.’

It’s easy to talk slavery in Bristol. But it’s best to make it local. ‘Mayor Charles Pinney was compensated £27,200 for 1,476 enslaved on 12 plantations in Nevis, St Kitts and British Guiana. That’s around £16.5m today. Pinney lived in the house over the road, and he worshipped here at St George’s’ (where we were performing).

People shuffled in their seats, looked around. Some sniffed the room.

I also tell stories of people migrating into the locality. In October 1914, two families called Bartholet moved to 73 Pembroke Road, Bristol. They’d previously spent ten days hiding in the cellar of their house in a small Belgian town, listening while German soldiers executed many men outside. An aunt was killed by a stray bullet. They escaped. While hiding in a wood, one of the mothers gave birth. They made it to Bristol, some of nearly quarter of a million Belgian refugees welcomed in Britain that autumn.

As the Bertholet children enrolled at school in Clifton, they must have borne great trauma inside. So, too, many of the refugees and asylum seekers arriving in Britain today. In London I talked of Eiad Zinah, a dentist from Damascus, whose frightening journey led to him working in Starbucks. Or another Syrian Milad Arbash - who watched others drown around him on a flimsy inflatable, reached Derby - and started at Marks & Spencer. Refugees have always had to fit in. But how easy is it to serve customers after viewing such horrors?

Fortunately there are people throughout Britain supporting them. For each performance of Human Cargo, as for my previous show The Transports, we partner with local support groups for refugees and asylum seekers. This Parallel Lives project now has a network of 50 groups across the country – from rural volunteers gathering clothes for Calais to sophisticated city organisations providing legal, financial and psychological support. The Refugee Council has been a strong support from the start. The current Human Cargo tour leads up to the remarkable UK Refugee Week (18-24 June) which celebrates what refugees bring to Britain.

History has always been shaped by the crossing of oceans by desperate people. Parallel Lives and Human Cargo seek to show, locally, how migration works both ways. In Glasgow, for example, my stories contrasted Patricia Nganga, a nurse who fled Congo Brazzaville and reached Glasgow, with John Lattimer, a handloom weaver from Paisley, exiled for life to New South Wales for a petty crime in 1829.

In crossing Britain we’ve found many sad tales: children dragged away as servants for the colonies … children trafficked here on banana lorries. We’ve met all sorts of refugee support groups, some polished, some shy, some providing housing, some attending to distress. We’ve seen the power of local story, and the value of putting a face on migration. And we’ve seen how history can broaden the debate beyond its current entrenchments.

- Matthew Crampton

Matthew studied Modern History at Pembroke College between 1981 and 1984.

Human Cargo tours until 17 June. See matthewcrampton.com for venues and for info about the book Human Cargo. Read the Parallel Lives stories across Britain at parallellivesproject.com.

June Dates for Human Cargo: 5 LIVERPOOL Philharmonic Hall; 7 SHOREHAM Ropetackle; 12 EXETER Phoenix; 13 DORCHESTER Shire Hall; 14 HALESWORTH The Cut; 15 LONDON Kings Place; 16 MATLOCK Florence Nightingale Hall; 17 BEDFORD The Place.