Locating Women’s Agency in Early Modern Spaces: Knowledge Exchange, History and Heritage

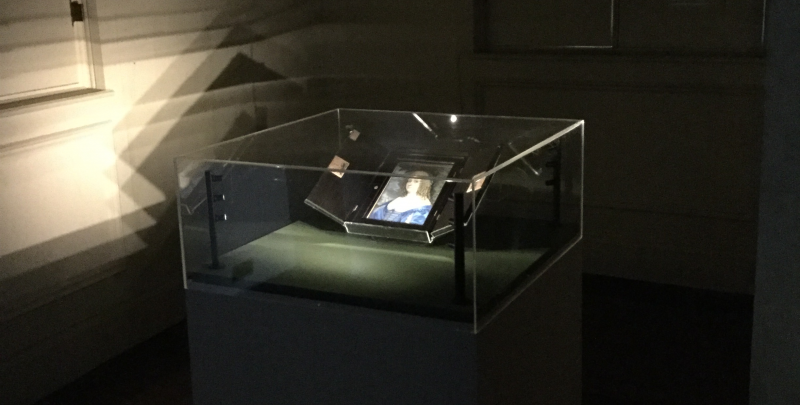

The glass case containing a portrait of Katherine Murray at Ham House, Richmond

In a small, darkened room above the north entrance of Ham House, Richmond, a solitary glass case displays a single painting. It hangs there not as an act of restoration, since there is no evidence the painting was ever kept in this closet, but as the culmination of a knowledge exchange project between the University of Oxford and the National Trust.

The aim of the project was to create a meaningful shift in the way that the early seventeenth-century part of Ham House’s story, prior to the grand alterations and extension of the Restoration era, was presented in the property. This painting, a miniature portrait of Katherine Murray (d. 1649) by John Hoskins the elder was an intriguing starting-point.

Katherine Murray lived at Ham House from 1626 with her husband, William Murray, and their children. William Murray was a close companion of Charles I, and from 1625 a groom of the king’s bedchamber. As a historian of early Stuart England, I was keen to discover what connections could be found between Ham’s collection and the political culture of the Caroline courts. Were the Murrays enthusiastic adopters of courtly tastes and fashions, and if they were, what does this tell us about the political, religious and aesthetic values that imbued the way they lived at Ham?

Between 1637 and 1639, the Murrays commissioned significant alterations to Ham House, much of which remains in situ. During this period Katherine sat for two portraits, one full-length oil by Anthony Van Dyck (c. 1637) and a large miniature by John Hoskins (1638). As a cultural survival, this miniature portrait offers tangible glimpse of the tastes and values of the royal family, their courtly followers, and wider élite society.

Katherine Murray, large miniature by John Hoskins (1638)

A sign that Katherine, as sitter, and William, as the likely patron, desired to emphasise their proximity to royalty is evidenced in the Hoskins portrait. Katherine’s representation consciously mirrors the way that Queen Henrietta Maria and other courtly ladies were fashioning themselves. Her hair is styled in tumbling ringlets that matched those adorning Henrietta Maria’s hair in the mid-1630s. Katherine is dressed in a revealing off-the-shoulder décolletage, which in 1638 represented the height of fashion, and was characteristic of the dress of the French-born queen. The bodice worn by Katherine is low-cut, showing off her delicate, porcelain flesh. She is depicted as being a woman of taste and beauty, ideals which in the courtly circles of the 1630s carried strong Neoplatonic resonances.

The dramatic array of pearls worn by Katherine further emphasise her family’s rising wealth and status. But the pearl, as the attribute of St Margaret – the patron saint of pregnant women – was also associated with fertility. Katherine may well have been pregnant when this piece was commissioned, as her daughter Margaret, the later Lady Maynard, was born around 1638. Fertility and reproduction provided the focal point of early modern female social spaces and community, and were central to Henrietta Maria’s representation of virtuous femininity in the 1630s.

In the Henrietta Maria’s portraiture, the white pearl is considered to signify the chastity and purity of the Virgin, and hence has been strongly connected with her Catholicism. The blue dress worn by the queen has also been connected to her efforts to alleviate the plight of Catholic recusants and priests. But whilst recent scholarship has drawn out the religious messages Henrietta Maria imbued in her portraiture, it is worth stressing that the new Caroline sensibility appealed to Protestant and not just Catholic followers of the queen. The cult of maternity and sacral femininity at Henrietta Maria’s court resonated with women across the religious divide, including Lucy Hay (née Percy), Countess of Carlisle, a lady of the queen’s bedchamber and a prominent Protestant at court.

What Katherine conveyed in her visual representation of the late 1630s, therefore, was her participation in the Franco-Italian artistic and cultural mores of the Caroline courts. But Katherine and William were also making active choices about the representation of themselves and their family. Katherine’s miniature appropriates the iconography of the queen in a particular way, celebrating female virtue and fecundity without necessarily embracing any overt religious stance. Above all, then, this portrait emphasises the loyalty, taste and good fortune of the Murrays as a family of influence, and the importance of art to the process of shaping and communicating their sense of self.

The Hoskins miniature of Katherine Murray is an object that still has the capacity to intrigue and delight. It continues to pose questions of the early Stuart age and the ideals, loyalties, and sensibilities that motivated a generation through a decade of conflict. By situating the object alongside the latest scholarly perspectives on women’s representation and political action in mid-seventeenth-century Britain, the new display and its accompanying volunteer-led tour aims to deepen visitor understanding and pique their curiosity.

The way that women’s lives and actions are represented in the heritage sector matters. Until very recently, there has been a tendency, at National Trust properties and elsewhere,

Dr Turnbull examining the Hoskins portrait

to frame women’s stories around themes of luxury, taste and fashion. This style of historical storytelling consequently perpetuates a misleading image of female domesticity, isolation and detachment from the fray of political and social change. The struggle of heritage properties to integrate women’s experiences into big, overarching historical narratives is the product of a much wider disconnect between innovations in gender history within academia and the general public.

Working with National Trust staff and volunteers on this Katherine Murray project has also revealed the complexity of deciphering the early modern period. Specialist training is needed both to discover female voices in the archives and to properly contextualise individual stories of female action and activism.

This is why I am delighted to have been given the opportunity to lead a new project, ‘Women and War: Female Activism during the English Civil Wars’, in partnership with the National Trust, as a TORCH Knowledge Exchange Fellow. I aim for this project to help communicate women’s stories of resourcefulness, resilience and radicalism during almost two decades of bitter and prolonged conflict.

Building on this successful collaboration with Ham House, I believe that there is an opportunity to provide other National Trust properties with new perspectives and fresh research-driven narratives about a formative period of national history. While continuing to work of the Murray women of Ham, I will also be partnering with Corfe Castle and Kingston Lacy in Dorset to tell the story of Lady Mary Bankes, the royalist whose estate was besieged several times by Parliamentarian armies before it was eventually taken in February 1646.

I hope therefore that by the end of this fellowship my project will have provided two National Trust properties with new ways of narrating and contextualising women’s Civil War experiences. In the process, I want to transform our expectations of the historical narratives that can be told at heritage sites and open up opportunities for scholars to build new collaborations.

-Emma Turnbull

Knowledge Exchange Fellow