Global War and Disease: The Making of Modern Bodies

One of the most popular and famous British portrayals of eighteenth-century imperial war is Benjamin West’s The Death of Wolfe, first displayed in 1771. This grand painting, measuring more than one and a half by two meters, provides a majestic and vivid image of a military hero’s death. It depicts a Christ-like death of the British commander James Wolfe, dying just as news is announced that British troops were victorious over the French at the 1759 Battle on the Plains of Abraham in New France. The painting was so popular that three full-size copies were commissioned, including one for Britain’s King George III. It was also influential in portrayals of warfare – the death of Nelson, for example, later received similar treatment. Death of Wolfe popularized the recent innovation of showing military officers in contemporary dress, rather than in the classical dress of togas. It thereby helped to establish the modern genre of history painting, which commemorated great moments such as the French Revolution, and in which it was modern subjects, modern settings, and modern dress that were portrayed, rather than the ancient world.

Death of General Wolfe - Benjamin West (1770)

West makes excellent use of a range of physical types and characters in his portrayal of imperial war. Surrounding Wolfe are figures that remind the viewer of all of the forces that came together in overseas war: a naval officer, identified by his blue uniform; a British regular soldier, identified by his eponymous redcoat; a Scottish Highlander wearing a kilt, with a shock of red hair; even a First Nation or American Indian in a muscular crouch, identified not only by his clothing but also by his skin colour, hair style, and relatively hairless body – something which contemporaries often remarked upon. The dramatic moment captures different types of humans, identified through physical characteristics as well as through changeable features such as clothes and postures. In other words, West portrays a successful empire. As empires are political entities that contain different types of people under their rule, West highlights how these different groups came together to achieve military victory.

European powers became increasingly involved in overseas wars during the mid eighteenth century. From the 1730s onwards, states such as Spain, Britain, and France ranged across the globe in their wars, fighting one another -- often allied with indigenous forces -- while also fighting against indigenous forces. For example, in the Seven Years War – the war portrayed by West – Britain and France fought one another in the Mediterranean, the Atlantic, in India, along the coast of Africa, in the Caribbean islands, and in North America; Britain and Spain also fought one another as far away as the Philippines. This global scope of warfare fundamentally shaped British and European societies, not only by drawing thousands of men to fight far afield, but also by wide-ranging logistical demands and the physical experience of fighting in foreign environments. While Europeans had travelled and settled in overseas areas for generations, these mid-century wars for the first time sent large concentrations of men – thousands at a time – to various corners of the globe, all within the span of a single generation.

Campaigning in a wide variety of foreign environments proved expensive and deadly to European armed forces, crippling their finances, logistics, and operations. Diseases such as yellow fever produced shocking symptoms (its nickname was the ‘black vomit’) and high death rates among newcomers. At Cartagena in 1741, for example, a British amphibious force quickly succumbed to disease, resulting in a humiliating British retreat, with only 3,000 troops of the original 11,000 still able to perform their military duties. In 1762, the British defeated Spanish defenders at Havana, but they re-embarked with only 880 fit for duty out of an original force of 11,000, with 3,000 troops dead from disease. Overseas wars thus provided ample opportunity for investigating foreign diseases; as the naval surgeon James Lind candidly stated, there is ‘a large field for medical observations, during a very sickly season in the West Indies, when thousands of Europeans are sent thither at once, in case of a war in that part of the world.’[1] With surgeons attached to each regiment and naval ship, eighteenth-century wars provided global networks of medical observations.

Drawing on a long tradition of humoural understandings of bodies and health, disease was understood not as the result of a particular infectious agent, but of a body in disequilibrium. Health, by contrast, was conceived as the state in which the body’s humours – or fluids – were balanced by one another. This conceptualization of the body’s functions meant that early moderns believed that bodies were particularly responsive to environmental factors, such as temperature, humidity, and diet. The physician John Lecaan, for example, likened bodies to thermometers and barometers, in that they changed in response to changes in the heat and density of the air. Indeed, he claimed that human bodies were even more sensitive to such atmospheric changes since a human ‘contains Fluids infinitely more subtle and refin’d than Mercury.’[2] Bodies were therefore understood as flexible and malleable, with changes to the environment outside the body triggering changes in the body itself. Given this understanding, disease in foreign environments was understood as initial disequilibrium while adapting to a new climate – what was described as being ‘seasoned’ to a new environment – even taking on new physical characteristics (different skin colour, for example).

Yet Europeans’ actual experience of overseas campaigning challenged such notions of adaptability and flexibility. High rates of disease among Europeans suggested to many that it might not be possible for bodies to adapt to different environments. Indeed, it suggested that these environments, with their accompanying diseases, were fundamentally foreign to Europeans. As the French military officer the marquis de Bussy noted in India, in 1758, the climate was ‘the biggest enemy that we have to fight.’[3]

West’s portrayal of overseas warfare is thus ingenious in part because of what it leaves out. Most notably, while his chosen battle took place in 1759 – a glorious year for British imperial arms – the painting itself was not completed and portrayed until the early 1770s, more than ten years later. By the year of its initial display at London’s Royal Academy in 1771, skirmishes had repeatedly broken out between American colonists and British soldiers, including the Stamp Act riots and Boston Massacre of 1770, with open war against British imperial rule to erupt just a few years later. West thus portrays empire in the midst of imperial crisis, outlining the ideal of empire. Death of Wolfe is an argument about what empire should be, rather than an accurate depiction of what it then was.

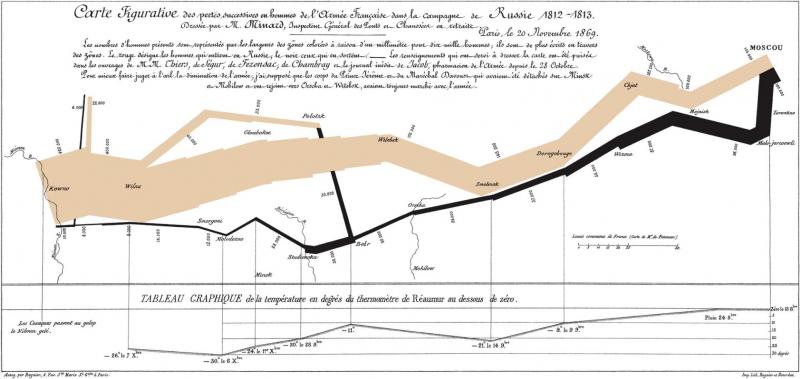

By focusing on a battle, West also avoids portraying the nature of campaigns, which could stretch on for months. Disease, which usually killed eight times as many troops as did combat before the twentieth century, is also absent in West’s image of global war. It is useful, in this context, to contrast West’s portrayal of war with Charles Minard’s portrayal of Napoleon’s Russian campaign. A French civil engineer, Minard was interested in how information and data was displayed, and his 1869 Carte figurative des pertes successives en hommes has been described as one of the best statistical graphics ever drawn.[4] Minard depicts Napoleon’s invasion of and retreat from Russia over the course of six months in 1812, with the thickness of a coloured column dwindling in precise relation to the loss of French manpower. His image captures the staggering loss of over 450,000 men – Napoleon starting out with half a million French troops but returning with only around 20,000. Minard focuses viewers’ attention on manpower, making it the protagonist that we follow. In contrast with West, Minard’s very subject is the passage of time, capturing the relentless problems of disease and logistics during campaigns in foreign territory. This was precisely Russian strategy: to drag out the French campaign for as long as possible, even to avoid battle, in order for the wastage of time to debilitate Napoleon’s military prowess.

Charles Minard's 1869 chart showing the number of men in Napoleon’s 1812 Russian campaign army, their movements, as well as the temperature they encountered on the return path.

West’s Death of Wolfe, by contrast, focuses on one battle – a moment in a campaign, rather than the campaign itself. This is all the more noteworthy in that the Battle of the Plains of Abraham was not decisive: it did not end the British campaign in Canada. While the battle itself lasted a few hours in the morning of 13 September 1759, the British maintained possession of Quebec throughout the winter, waiting for reinforcements from Britain that reached them only when the St Lawrence waterway thawed in spring 1760. Whereas the battle itself yielded 58 British fatalities, over 460 died from disease in the winter months that followed. Moreover, scurvy and camp diseases crippled the British army -- of an initial force of 7,000, only 2,612 were still fit for service in April 1760.

The British naval surgeon James Lind, well known today for his writings on scurvy, collected reports and data collected in these overseas campaigns, including the 1759-60 siege of Quebec and campaigns in the West Indies. He systematized his findings in his influential An Essay on Diseases Incidental to Europeans in Hot Climates (1768). Translated into a variety of European languages and republished into the nineteenth century, Lind’s global overview of diseases linked diseases to regions, helping to establish today’s medical sub-discipline of tropical medicine. While ‘tropical medicine’ is often also known as ‘international health,’ its roots lie firmly in European imperial wars. As the title of Lind’s book makes clear, this was a European perspective: it was about Europeans fighting overseas, European experiences of diseases, and solutions to Europeans’ susceptibility to foreign diseases. Many of these overseas regions, in areas that became part of nineteenth- and twentieth-century Western empires, were thereby grouped together under the heading of ‘hot climates’, or what became known simply as ‘the tropics’. They were designated as different from Europe’s temperate climates, as well as more disease-ridden than European environments. This designation, too, represented a European perspective: such environments were by no means more disease-ridden for locals who lived there.

The global scope of eighteenth-century war thus encouraged the development of European categories for understanding the world, including notions of what it meant to be European. At the same time, these observations and categories contributed to developing notions that bodies were not flexible or adaptable; that instead they were fixed physical entities, governed more by biological inheritance than environmental influences – concepts that undergird modern biomedicine, as well as notions of genetics, eugenics, and race. West’s portrayal of war, even if avoiding depictions of disease, calls attention to these shifting definitions of identity and the crucial role of bodies in wartime, whether as manpower or as imperial categories of difference.

[1] James Lind, An Essay on Diseases Incidental to Europeans in Hot Climates (1768), 121.

[2] John Polus Lecaan, Advice to the Gentlemen in the Army of Her Majesty’s Forces in Spain and Portugal (1708), 19-20, 20.

[3] Marquis de Bussy to the comte de Lally, 15 July 1758, Service historique de la défense, Vincennes, A1 3541, fo. 24.

[4] Edward Tufte, The Visual Display of Quantitative Information (1983), 40.