A Garden Shed for Clio's House?

This is an age when assignation to identity groups or social media communities comes easily. Why, therefore, is there no ready description for those who, at the conclusion of non-academic careers, pursue serious historical research? ‘Independent scholar’ is the default terminology of conferences and research articles. Yet this pleasing suggestion of the wandering eccentricity of the ‘Scholar Gipsy’ does not really hit the mark. ‘Citizen scholar’ is much in vogue but the concept, admirable in its way, defies practical definition. ‘Amateur historian’, possibly, but the misplaced sneer of ‘hobbyism’ inevitably follows.

Perhaps the ability as a ‘senior citizen’ to indulge an enduring fascination with historical investigation is a recent development: traditional career patterns have become more flexible just as access to research resources is more open. So it is unsurprising that the concept should lack a brand. After all, its counterpart of the professional career historian is itself a relative newcomer. Previously, most historians were ‘hobbyists’ determinedly free of institutional affiliation. Where is the Oxford history graduate who does not recall Gibbon’s ringing declamation: “To the University of Oxford I acknowledge no obligation; and she will as cheerfully renounce me for a son as I am willing to disclaim her for a mother”.

Is there, then, a new breed of historian aiming at professional standards but largely invisible in a field dominated by an institutional ethos? Is there a resource here that remains unrecognised because it falls outside conventional notions of career progression? Problems of identification are probably compounded by the often fortuitous nature of independent entry into the world of historical research. And so, by way of illustration, to the fortuitous and personal…

Six years after going down from Oxford I was disgorged from a rusting coastal steamer onto the even more dilapidated wharf of a small riverine town in Malaysian Borneo. Waiting for me, preoccupied with wedding arrangements, was my fiancé accompanied by a gaggle of curious Chinese, Dayak and Malay onlookers. It was only during casual conversation that I learned she had recently survived a communist ambush and the brutal execution of her schoolteacher friend. Anonymous phone calls in Mandarin threatened retribution if she went near the security services.

Nevertheless, life went on. On a monsoon-laden tropical evening our wedding reception was held with much brandy, fairy lights and Malaysian Rangers patrolling the perimeter against a chance grenade lobbed from the nearby jungle fringe. Later, back in London, came a time for reflection. How did all this match the stereotyped Cold War and colonial narratives still dominating political discourse? ‘Very little’ had to be the response. There was too much below the surface needing exploration and explanation. I was set on the road of historical research.

Only since retirement has it been practicable to indulge this quest in anything approaching a professional manner. Beforehand it was possible to refine a rudimentary knowledge of local languages and build up local knowledge. But thorough archival research and purposive interrogation of secondary sources need substantive commitment. Inevitably an initially narrow interest was drawn into wider expanses of political, economic, cultural and environmental history – certainly sufficient to gainsay Simon Schama’s remark in personal correspondence that “I didn’t realise Borneo had a history”.

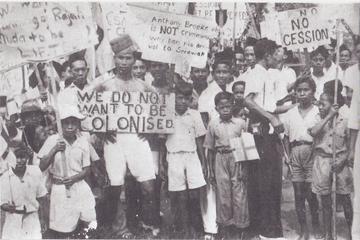

Even so, is Borneo history a murky niche worthy only of the jobbing specialist and parochial aficionado? It can at best be a cursory adjunct of the more neatly compartmentalised histories of Malaysia, Indonesia and South-east Asia. Constantly recycled accounts have changed little over decades with questionable national independence heroes spatchcocked onto an essentially colonial narrative. Yet beneath this officially approved carapace is an immense richness of historical experience and community agency, none more so than in the perennially neglected roles of women ranging from jungle guerrilla fighters to dynamic business entrepreneurs.

Correspondingly there is an unrequited domestic demand for ‘real history’, whether reflected in online community blogs or more cautiously expressed at the fringes of academic conferences. The need for fresh historiographical approaches is evident. The previously concealed colonial records of the ‘migrated archives’, for example, have attracted local interest in a selective political context, yet provide a hidden treasure trove of political and social history. Equally ignored has been the potential for a robustly transnational approach capitalising on the diversity of Borneo’s communities and cultures as a counterpoint for historical experience in the wider region.

Some aspects of Borneo history have a particularly British, even Oxford, resonance. Kenelm Digby, the endearing if exasperating proposer of the Oxford Union’s notorious ‘King and Country’ motion, served the White Rajahs of Sarawak to be pursued even in that remote imperial outpost by the British security services. The beginnings of Voluntary Service Overseas in Sarawak, progenitor of similar international service movements, and the roles of founder Alec Dickson and Malcolm MacDonald, both Oxford men of agreeably nonconformist disposition, also merit inclusion in the historical record. Above all, the Cold War saga of Confrontation with its intertwined communist insurgency demands historical revision as its lessons for British military capability, radicalisation and counter-terrorism, decolonisation, deforestation and climate change and the shifting global balance of power centred on the South China Sea become clearer.

It has been a privilege to engage afresh in ‘history from below’ and, in so doing, look for renewed tutorial inspiration in the work of Keith Thomas, Richard Cobb and other doyens of Oxford history. There have been frustrations, some familiar to any early career researcher, others peculiar to the institutional outsider. Academic reactions to amateur intrusion sometimes recall Dr Johnson’s aphorism about the dog standing on its hind legs: that the surprise is not that it is done badly but that it is done at all. Responses from Oxford historians, on the other hand, have been invariably generous and constructive. Surely there are others out there essaying their own contribution to the community of scholarship. If so, perhaps there is room for a modest garden shed adjacent to the many mansions of Clio’s house.

David Phillips

(formerly St John’s College 1961-66)