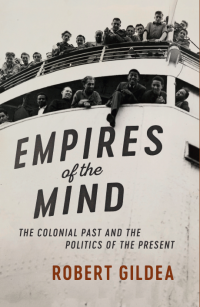

Empires of the mind: the colonial past and the politics of the present

Professor Robert Gildea (Worcester College)

‘When the history books come to be written’ is a favourite trope used by politicians anxious that the verdict of history may not be as kind to them as they would like. ‘When the history books are written’ said Prime Minister Theresa May on 14 January 2019, ‘people will look at the decision of the House tomorrow and ask: did we deliver on the country’s vote to leave the European Union?’

As it happens, many books have already been written on Britain’s decision to leave the EU, by the likes of Anthony Barnett, Anand Menon, Tim Shipman, Kevin O’Rourke and Fintan O’Toole. They did not know whether parliament would deliver on the referendum result, and the outcome of any decision indeed not be the main question. Much more interesting is: how did we get into this predicament, why is it so intractable, and what does it all mean for Britain, Europe and the world?

Empires of the mind did not begin as a book about Brexit. The original question of the Wiles Lectures I gave in Belfast in 2013 was: how did France, liberated by resistance movements in 1944, so quickly descend into of colonial wars, especially the Algerian War of 1954-62, that drove a permanent wedge between the metropolitan French and those of colonial origin. The hierarchies, exclusions and violence of colonial rule returned to haunt the metropolis as what has been called the ‘colonial fracture’ in contemporary France. As I progressed, I decided that I had to explore whether the French case was exceptional and therefore widened my lens to study a subject that was new to me: the ambitions and anguish of British colonialism.

Put very briefly, the book concludes three things. First, that the formal ‘decolonisation’ of the 1960s did not end the colonial story. Both Britain and France constantly reinvented colonialism, as neo-colonialism in the 1960s and 1970s, global financial imperialism in the 1980s and 1990s, and after 9/11 a New Imperialism that was concealed behind the War on Terror. Although France did not take part in the Iraq invasion of 2003, she pursued neo-colonial policies in Africa and alongside the British and Americans in Libya and Syria. These brutal interventions deepened the colonial fracture, alienated Muslim populations abroad and at home and went a long way to provoking the ‘blowback’ of al-Qaeda, ISIS, the Charlie Hebdo and Bataclan attacks in Paris in 2015 and the jihadist attacks in Paris and Manchester in 2017.

Second, the withdrawl from empire coincided with the immigration to the metropolis of former colonial peoples, often in order to take part in postwar economic reconstruction. This, however, was often experienced in host countries as a painful reminder of the loss of empire, and as an ‘invasion’ by people of colour, infamously highlighted by Enoch Powell’s 1968 ‘Rivers of Blood speech. Immigration was dealt with by the homegrown population by imposing ‘colour bars’ in housing, education and jobs and by resorting to racial violence. This, in effect, re-established colonial hierarchies in the metropolis. Although there were initiatives to develop multiculturalism, the perceived threat of Islamism from the 1990s dictated a retreat to monocultural nationalism. This was achieved in France by an insistence of secularism in public places and in the UK by the rhetoric of ‘British values’. Both implicitly excluded Muslim communities. Meanwhile the ‘hostile environment’ immigration announced by Theresa May in 2013 led directly to the Windrush scandal in 2018.

Thirdly, attitudes to empire and immigration impacted on attitudes to Europe. Here, though, France and Britain diverged. France never saw a contradiction between her neo-colonial ambitions in Africa, in what became known as Françafrique, and her commitment to Europe. For Britain, the choice was always ‘either, or’. Joining the Common Market was widely felt as a defeat, intensifying the pain of the loss of formal empire. Whereas France put herself at the heart of the European project, Britain remained on the periphery, and resented what it saw as the domination of Europe, first by France through Jacques Delors, then, after the fall of the Berlin Wall, by Germany. ‘This is all a German racket designed to take over Europe’, Thatcher’s Trade and Industry Secretary said of monetary union in 1990. ‘I’m not against giving up sovereignty in principle, but not to this lot. You may as well give it to Adolf Hitler’. Ridley lost his job then for comments that are now commonplace. During the referendum campaign of 2016 fantasies were concocted that a ‘global Britain’ would break way from ‘vassalage’ to Europe’s in order to re-establish a ‘swashbuckling’ trading empire, the ‘Anglosphere’ or ‘Empire 2.0’.

The debate on Europe is, of course, about much more than empire. Britain is undergoing a crisis of identity, torn between embracing multiculturalism and defending a monocultural fortress. It is undergoing convulsions that Germany and France went through after the Second World War which Britain, because it told itself the story that it ‘stood alone and ‘liberated Europe’ did not feel the need to face. It is a former great power that has not yet come to terms with the fact that it is now at best a medium-sized power. The more they feel power slip away, the more many Britons think that they can, by sheer force of will, ‘make Britain great again’.

All this brings us back to the question: can history books have any influence on public consciousness? Probably not. The British have never liked public intellectuals and have now had enough of experts too. The referendum set popular opinion against the ‘establishment’ and the ‘metropolitan liberal elite’. Warnings about the hit the economy and society would take as a consequence of ‘no deal’ were dismissed as Project Fear. The British enjoy retelling the Second World War and bathing in imperial nostalgia. It is possible that out of this end-of-empire convulsion will rise a new feeling that Britain should embrace a less fanciful view of itself as a medium-sized power that gains from cooperation with its European neighbours. But perhaps that too is fanciful.

Professor Robert Gildea

Professor of Modern History

Worcester College