Did the Hundred Years War against France strengthen a sense of English national identity?

Key words: Empire; Identity; War; Religion; Ideas; Government; Communications

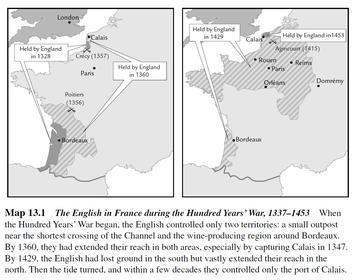

Figure 1 - Map of the English territories in France during the Hundred Years' War, 1337-1453 Medieval Europe Online

In 1337, King Philip VI of France confiscated the duchy of Aquitaine, a territory in south-west France, from Edward III, king of England (see Figure 1). The duchy had been attached to the English crown since Henry II’s marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine in 1152, but the king of France now wanted to bring it more firmly under French royal control. Tensions had been building for some time, but the final straw came when Edward III allowed a rebel against Philip VI, named Robert of Artois, to shelter in Aquitaine. In response, Philip confiscated the duchy. The stakes were raised further in 1340 when Edward III claimed the French throne himself by descent from his mother Isabella, a French princess. These events marked the beginning of the long-running conflict between England and France which lasted until 1453 and became known as the ‘Hundred Years War’.

Initially, the conflict was not so much a national war between England and France as a dynastic conflict between two monarchs over a particular territory. Consequently, Edward III had to persuade the English population to view the war as a conflict not just between two kings but between two entire kingdoms and their inhabitants. This would enable him to draw on a much broader basis of support for the war.

The English government used various methods to persuade the population that war was in the national interest. Demands for taxation and military service were explained in parliament, which authorised tax grants on behalf of the kingdom. These explanations were then transmitted back to the localities by MPs and local government officials such as sheriffs, through proclamations in the county court (the centre of local government) and in marketplaces. Newsletters about the progress of the war were disseminated across the kingdom, and negative stereotypes of the French were repeated in songs, poems, and chronicles.

Another important means by which the government disseminated information was through the church. With a church in every parish in the kingdom, this was an excellent way to spread news widely. Bishops sent out orders to parish priests to hold special prayers, religious services, processions, and sermons in support of the war. Sometimes, these events were a thanksgiving for a military victory, which reinforced the idea that God was on the side of the English. On other occasions, when the war was going badly, church services included special prayers of repentance, as it was believed that the sins of the English people had caused the war to go badly. Image 2 (right) shows a preaching cross, where people would gather to hear sermons. These were a common feature of medieval churchyards and market squares.

One of the most famous of these was St Paul’s Cross, in the grounds of St Paul’s Cathedral, London, where large crowds would gather to hear preachers (Figure 3). This was where the bishop of Rochester, Thomas Brinton, preached a sermon in 1375, at a time when the war with France was going badly. In the sermon, he blamed English military failure in France on the sins of the English people at home, saying: ‘I fear that because of all our sins, our kingdom has decayed and collapsed, and God, who used to be English, has withdrawn from us.’ This type of preaching encouraged the English people to view the war as something that involved them, even if they were not fighting in France. It linked war, religion, and national identity together in people’s minds by suggesting that God was on their side, and that their prayers and good behaviour could make a real difference to the outcome of the war.

Questions for classroom discussion

1. Why was it important for Edward III to present the war against Philip VI of France as a national enterprise?

2. How was the medieval royal government able to spread propaganda in a period of history before technologies of mass communication existed?

3. In what ways was religion used to promote war and reinforce a sense of national identity during the war with France?

4. How do governments persuade people to support war and regard it as being in the national interest

Author Details

Dr Andrea Ruddick (Lecturer in Medieval History, Exeter College)

Andrea works on national identity in Britain and Ireland in the middle ages. She is interested in sermons as a form of political propaganda in the late middle ages.

Figure 2 - A preaching cross