Carnal Knowledge: Regulating Sex in England, 1470-1600

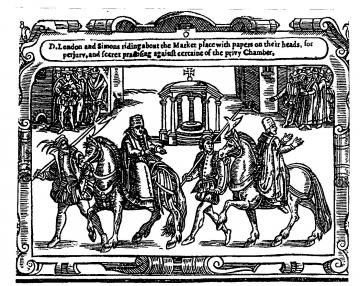

Fear stalked the city! Already a religious revolution was in train – traditional practices were being abandoned, images torn down and smashed, new vernacular forms of worship came into use. Now the strident supporters of the new order – some clerics among them sporting patriarchal beards to mark them off from their conservative brethren – were going after sexual offenders. In each ward of the city, local jurors were required to seek out and report not only notorious prostitutes, pimps and bawds, but also run-of-the-mill adulteresses, whoremongers and fornicators. (It was notorious that many wealthy and some not-so-wealthy men kept mistresses in alehouses, lodgings, or even their own residences.) Offenders arraigned and found guilty by the magistrates were variously ducked, whipped, imprisoned, pilloried, ridden backwards on horses or carted round the streets in shameful procession while the bystanders jeered, flung filthy objects and doused them with dirty water. Often they were expelled from their wards or from the city itself. Even men of some substance were not immune from these public penalties, but females probably bore the brunt – it was said that ‘very many women were disgraced who had always before enjoyed good reputations’.

Penance with Fustigation (from John Foxe's Book of Martyrs)

By permission of Brasenose College

These events are reminiscent of the moral purges carried out in recent years by such groups as the Taliban and ISIS. But those I have described actually took place in England in the reign of Edward VI (1547–53), the ‘young Josiah’ to whom fervent Protestants looked to complete the Reformation begun by his father, Henry VIII. They deserve to be better known as a striking episode of the early English Reformation. But does this mean that campaigns against sexual licence were a product of Protestantism? The case has often been made for Scotland and for the states and cities of continental Europe, sometimes on the basis of imperfect evidence. In England the Protestant vision certainly gave an extra fillip to the reform of sexual ‘manners’ in these years, renewed in the reign of Elizabeth. In London, the civic purge around 1550 had been prefaced in 1546 by the closure of the string of licensed brothels known as the Southwark ‘stews’, while in 1553 the city set up Bridewell Hospital to administer the sharp medicines of imprisonment and whipping to cure the ‘idle poor’, deemed to include sexual offenders of all kinds.

Likewise in many provincial towns in the reign of Elizabeth (1558–1603), the magistrates stepped up action against sexual vice – some offenders were whipped, but the characteristic penalty was ‘carting’ round the streets. Meanwhile committed Protestant judges and administrators were trying to reform the ecclesiastical courts – so closely associated with policing sexual vice that they were colloquially known as the ‘bawdy’ or ‘bum’ courts – to make them more effective instruments of discipline. ‘Visitations’, tours of inspection by bishops and archdeacons to seek out offenders, became more regular and more systematic, while efforts were made to make public penance, the shame penalty usually imposed on sexual offenders, a more effective spur to true repentance. Culprits were required to make open confession and to show clear evidence of contrition, for example by shedding tears. In the early part of Elizabeth’s reign, it became common in many places to require penance to be performed in the marketplace as well as, or instead of, in church.

But these initiatives were made easier because, long before Luther, Zwingli, Calvin and others preached their new Protestant doctrines, English ecclesiastical and secular courts were already active in policing sexual sin. In the late fifteenth century the London church courts mounted huge numbers of prosecutions for adultery, fornication and ‘bawdry’ (pimping, procuring, and other forms of aiding and abetting sexual offenders). The civic authorities also took a hand. Locally offenders were regularly ‘presented’ by wardmote inquests – recidivists being eventually driven out of the ward – while the mayor and aldermen made an example of notorious offenders by subjecting them to spectacular shame punishments. In 1473 the city magistrates in alliance with the ascendant Yorkist government of Edward IV organized a major drive against bawds and prostitutes comparable with the purge of Edward VI’s reign. Provincial magistrates, for their part, saw the policing of sexual morality as part of their duty, essential for the ‘good worship’ of their towns. In the late fifteenth century, civic and ecclesiastical authorities can sometimes be observed in a kind of virtuous competition, striving to outdo each other in their efforts to reform vice. Records of the punishments that these late medieval magistrates meted out in places such as Exeter were seized on as precedents by their Elizabethan successors.

Riding Backwards (from John Foxe's Book of Martyrs)

By permission of Brasenose College

So there were continuities across the Reformation divide, as well as striking new departures. Towards the end of the sixteenth century, shifting circumstances caused further mutations. The crown, alarmed by the activities of more extreme Puritans, became hostile to the mingling of ecclesiastical and secular jurisdiction and indeed to legal innovation more generally. This wariness hampered those who wanted to tighten the net of legal sanctions. Even the work of Bridewell came under scrutiny. But for many ecclesiastical judges, zeal for sexual regulation was in any case waning as Reformation became routine, so by 1600 marketplace and multiple penances had become much less common. Meanwhile, changing social and demographic conditions tilted the agenda of sexual regulation in a different direction. Till at least the mid sixteenth century, the authorities were concerned mainly with sex-trade professionals and with irresponsible householders – notorious adulterers and adulteresses, masters who exploited their maidservants, men and women who at a price would receive suspect persons under their roof with no questions asked. In contrast, courting couples who seemed to be heading towards marriage were often left unmolested (though they may have been privately admonished by their priests before compulsory auricular confession was abolished in 1548). In the late sixteenth century, population pressure and growing poverty contributed to increasing hostility to illegitimacy and, more generally, sharpened attitudes to premarital sex. In 1576, in the context of poor law legislation, JPs were authorized to make orders for the maintenance of illegitimate children and (at their discretion) to punish the parents. Thereafter the most characteristic consensual sexual offences prosecuted in both the secular and the ecclesiastical courts centred on bastardy. Another late Elizabethan innovation tending in the same direction was the routine prosecution of couples, married by the time the case came to court, for ‘antenuptial incontinence’ or bridal pregnancy.

To sum up, in both late medieval and early modern England the regulation of sexual behaviour by legal means was a commonplace of social life. But if 1600 is compared with 1550 and again with 1500, the precise pattern was by no means the same. These continuities, changes and subtle shifts, explored in various social contexts (metropolitan, urban, rural in different parts of England) are the subject of my book!

- Dr Martin Ingram

Carnal Knowledge: Regulating Sex in England, 1470–1600 (Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History), (CUP, 10 March 2017)

How was the law used to control sex in Tudor England? What were the differences between secular and religious practice? This major study reveals that - contrary to what historians have often supposed - in pre-Reformation England both ecclesiastical and secular (especially urban) courts were already highly active in regulating sex. They not only enforced clerical celibacy and sought to combat prostitution but also restrained the pre- and extramarital sexual activities of laypeople more generally. Initially destabilising, the religious and institutional changes of 1530–60 eventually led to important new developments that tightened the regime further. There were striking innovations in the use of shaming punishments in provincial towns and experiments in the practice of public penance in the church courts, while Bridewell transformed the situation in London. Allowing the clergy to marry was a milestone of a different sort. Together these changes contributed to a marked shift in the moral climate by 1600.

See a review of the book on Reviews in History

An Interview with Dr Ingram regarding his book can be read here: http://notchesblog.com/2018/02/13/carnal-knowledge-regulating-sex-in-england-1470-1600/