Boston King and the Black Loyalists of the American Revolution

Key words: Migration; Empire; Identity; Liberty; Survival; War; Religion; Role of individuals in encouraging/inhibiting change; Race; Slavery; Revolution; America; Africa; Sierra Leone.

In the eighteenth century, black soldiers played a crucial role in the British military (see Figure 1). During the American Revolutionary Wars (1776-1783), British commanders offered freedom to enslaved people

Figure 1 - Detail from John Singleton Copley, ‘The Death of Major Peirson, 6 January 1781’, (1783) Tate Gallery, London.

willing to turn against their Patriot ‘masters’ and join the ‘Loyalist’ army. Many thousands of the enslaved took the offer up, risking their lives for their chance for freedom. Boston King (c.1760-1802) was one of these ‘black Loyalists’. His autobiography is one of only a handful of accounts of the Revolution written by rank-and-file Loyalist soldiers.

Born in South Carolina around 1760, King spent his childhood and young adult years working as a house-slave and cattle-herd on a large farm, about 28 miles from the state capital Charlestown. When Loyalist forces seized Charlestown in May 1780, King took his opportunity to escape slavery and enlisted with the British (excerpt A, below).

As soldiers in the Loyalist army, former slaves were often given the most dangerous missions. In 1781, King was sent alone to gather reinforcements when his battalion was under siege at Nelson’s Ferry (excerpt B). This was a doubly dangerous mission; the gentlemanly code of conduct that prevented prisoners of war from being tortured or summarily executed did not apply to so-called ‘runaway slaves’. If King was captured, he could expect no mercy.

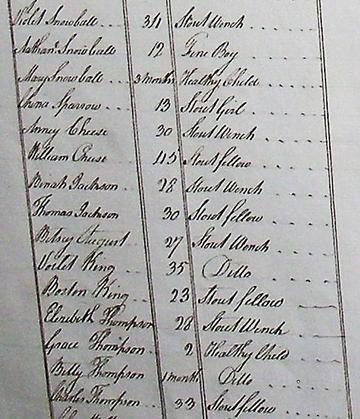

King was successful in his mission, but by the end of 1781 it was clear that the Loyalist war effort was hopeless. King travelled first to New York, but after the British acknowledged defeat in 1783, he and his wife Violet were evacuated to Nova Scotia, Canada. Boston and Violet King were among about 3000 such black Loyalist evacuees. Their names were recorded by British forces in a ledger known as the ‘Book of Negroes’ (see Figure 2). This source – now freely available online ( http://www.blackloyalist.info/) – demonstrates the scale of the evacuation, and also suggests how British military officials viewed their black comrades. Violet, for instance, was recorded simply as a ‘stout wench’.

Figure 2 - Detail including Boston and Violet King’s entries from ‘The Book of Negroes’, 1783

Once the family had settled in Nova Scotia, King was ordained as a Methodist minister and began to preach the gospel. Here he became interested in working as a missionary in Africa. His thoughts about the ‘wretched condition’ of the ‘poor creatures’ who ‘had never heard the Name of God or of Christ’ (excerpt C) may seem surprising when we consider that his parents were both African, but they were reflective of common evangelical attitudes about non-Europeans, and especially those of non-Abrahamic faiths.

King had other good reasons for wanting to go to Africa. Loyalist refugees, both black and white, had been relocated to Nova Scotia at the end of the war, rapidly increasing the local population. Many of the white Loyalists had themselves owned slaves in America. Now, in Canada, they were in competition for work and business. The scarcity of employment, food and even natural resources, combined with undoubted racial prejudice from the white migrants, made life very difficult for the black Loyalists in Nova Scotia.

A similar situation had developed in London, where many more black Loyalists had chosen to settle after the war. Work was scarce enough, but some Loyalists, like Billy Waters, had been wounded in the line of duty and could not now get regular employment. Waters was only able to survive because he was a talented musician, and he became well-known as a busker, playing his fiddle on the streets of London. For many of London’s eighteenth-century black migrant population, the prospect of starting again in Africa was an attractive one.

They got their chance when the British established a viable colony for freed slaves in Sierra Leone, West Africa in 1791 (excerpt D). Boston and Violet set sail from Nova Scotia for the new colony in January 1792, and arrived at Freetown, Sierra Leone, on 6 March. Sadly, Violet quickly caught malaria, and died less than a month later. King continued to preach the gospel, and set up a Christian school nearby for African children.

In 1794, King migrated again, this time to Britain, where he trained at Kingswood School near Bristol ‘that I might be better qualified to teach the natives’. He continued to preach while he was in Britain, and his experience with other Methodists there helped him to overcome his distrust of white people (excerpt E). He studied at Kingswood for two years and wrote his autobiography before returning to Sierra Leone in 1796. The ‘Memoirs of the Life of Boston King’ were published in instalments in The Methodist Magazine in 1798.

Boston King continued to preach and teach the gospel in West Africa for the rest of his life. He died in Sherbro, about 100 miles south of Freetown, in 1802. His travels brought him into contact with many of the great upheavals of the eighteenth century. Slavery, revolution, migration, colonialism, and evangelicalism were only a few of the major themes illuminated by his fascinating and complex life story.

Questions for classroom discussion

- Can we call Boston King a ‘war hero’?

- How did Christianity/Methodism affect Boston King’s view of the world?

- How did Boston King’s experiences affect his attitude towards Britain and British people? How did this change over time?

- Why did some of the black Loyalists want to go to Sierra Leone? What challenges did they face when they got there?

Supplementary materials

Searchable database of black Loyalists: http://www.blackloyalist.info

Full text of Boston King’s ‘Memoirs’, along with a teaching guide by Professor Joe Lockard, Arizona State University: http://antislavery.eserver.org/narratives/boston_king/

Information for teachers

Boston King’s testimony demonstrates how a biographical or microhistorical approach can draw together many of history’s ‘big themes’ in one coherent story: revolution, migration, war, slavery and liberty all played significant parts in his life. Especially with a history as large as that of transatlantic slavery, it is all too easy to reduce complex individuals to abstractions; the experiences of twelve million enslaved men, women and children are too often seen as part of a single monolithic ‘system’. Studying the work of authors like King reminds us that these ‘big pictures’ are made up of the actions of many millions of people – and not only those we have traditionally seen as being powerful or influential.

Excerpts

All from: Boston King, ‘Memoirs of the Life of Boston King’ in: Anon. (ed.), The Methodist Magazine, for the Year 1798; Being a Continuation of The Arminian Magazine (London: G. Whitfield, [1799]), pp. 105-110, 157-161, 209-213, 261265.

Excerpt A

Having obtained leave one day to see my parents, who lived about 12 miles off, and it being late before I could go, I was obliged to borrow one of Mr. Waters’s horses; but a servant of my masters, took the horse from me to go a little journey, and stayed two or three days longer than he ought. […] I expected the severest punishment, because the gentleman to whom the horse belonged was a very bad man, and knew not how to shew mercy. To escape his cruelty, I determined to go to Charles-Town, and throw myself into the hands of the English. They received me readily, and I began to feel the happiness of liberty, of which I knew nothing before, altho’ I was much grieved at first, to be obliged to leave my friends, and reside among strangers.

Excerpt B

Our situation was very precarious, and we expected to be made prisoners every day; for the Americans had 1600 men, not far off; whereas our whole number amounted only to 250: But there were 1200 English about 30 miles off; only we knew not how to inform them of our danger, as the Americans were in possession of the country. Our commander at length determined to send me with a letter, promising me great rewards, if I was successful in the business. I refused going on horse-back, and set off on foot about 3 o’clock in the afternoon. I expected every moment to fall in with the enemy, whom I well knew would shew me no mercy. I went on without interruption, till I got within six miles of my journey’s end, and then was alarmed with a great noise a little before me. But I stopped out of the road, and fell flat upon my face till they were gone by.

[…] I came to Mums-corner tavern. I knocked at the door, but they blew out the candle. I knocked again and entreated the master to open the door. At last he came with a frightful countenance, and said, “I thought it was the Americans; for they were here about an hour ago, and I thought they were returned again.” […] When we had gone about two miles, we were stopped by the picket-guard, till the Captain came out with 30 men: As soon as he knew that I had brought an express from Nelson’s-ferry, he received me with great kindness, and expressed his approbation of my courage and conduct in this dangerous business.

Excerpt C

In the year 1787, I found my mind drawn out to commiserate my poor brethren in Africa; and especially when I considered that we who had the happiness of being brought up in a Christian land, where the Gospel is preached, where notwithstanding our great privileges, involved in gross darkness and wickedness; I thought, what a wretched condition then must those poor creatures be in, who never heard the Name of God or of Christ; nor had an instruction afforded them with respect to a future judgment. As I had not the least prospect at that time of ever seeing Africa, I contented myself with pitying and praying for the poor benighted inhabitants of that country which gave birth to my forefathers.

Excerpt D

An opportunity was afforded us of removing from Nova Scotia to Sierra Leone. The advantages held out to the Blacks were considered by them as valuable. Every married man was promised 30 acres of land, and every male child under 15 years of age, was entitled to five acres. We were likewise to have a free passage to Africa, and upon our arrival, to be furnished with provisions till we could clear a sufficient portion of land necessary for our subsistence. The Company likewise engaged to furnish us with all necessaries, and to take in return the produce of the new plantations. Their intention being, as far as possible in their power, to put a stop to the abominable slave-trade

Excerpt E

I found it profitable to my own soul to be exercised in inviting sinners to Christ; particularly on Sunday, while I was preaching at Snowsfields-Chapel [in London], the Lord blessed me abundantly, and I found a more cordial love to the White People than I had ever experienced before. In the former part of my life I had suffered greatly from the cruelty and injustice of the Whites, which induced me to look upon them, in general as our enemies; And even after the Lord had manifested his forgiving mercy to me, I still felt at time an uneasy distrust and shyness towards them; but on that day the Lord removed all my prejudices; for which I bless his holy Name.