Why I am Studying History

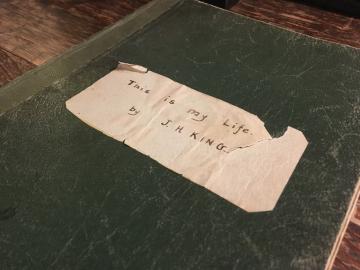

Ten years ago, my Dad gave me a notebook. It was small and square, hardback, with a flaking moss-green cover and paper-thin pages. On the front, it said, simply, “This is my life”, and then a name: J.H. King, my great-uncle.

My great-uncle’s notebook is an account of his life, written in his old age. It tracks a working-class London life that began in 1907 and spanned two world wars, an economic depression, and significant social upheaval. Sprinkled in among the seismic events of the twentieth century are his own vivid memories: running full pelt, scared of the dark, down an alleyway to the sweet shop; being given an Oxford rosette while watching the Oxford-Cambridge boat race in 1912, in which both crews regrettably sank; eating gobstoppers in a field full of buttercups after recovering from influenza in 1919; and spending all his money on a ticket to the very first FA Cup final at Wembley in 1923, where he sat on the ground by the touch line, tripping up Ted Vizard, Bolton’s left-winger, with his spindly legs. The account ends prematurely in 1945, his handwriting growing slowly fainter and more tentative before trailing off and leaving us, forever, dodging V-1 bombs in Neasden.

I was enchanted by his notebook, and by the time I’d read all fifty-eight pages I felt the loss of the last years of his life as keenly as if I’d had a novel wrenched away from me ten pages before the end. I wanted to stay submerged in his account of years that he’d lived and I hadn’t.

I had always loved history, and it was always the people, the everyday, and the minutiae that fascinated me most. More than anything else, and before I’d got to university and discovered social history, my great-uncle’s autobiography impressed upon me the value of the everyday man and woman in the study of history. From then on, I have always sought to ask the same questions: not just why and how something happened, but where people like my great uncle, or my brilliant, bingo-calling Grandad, or my indomitable grandmothers would have fit in, and how they made and understood history as it was happening around them.

After an undergraduate degree at Warwick, a year abroad at UCLA, and an MSt at Oxford, these questions led me to a DPhil. As our research so often does, my focus emerged from a fusion of my historical interests in post-war Britain, feminism, and the welfare state, and my own more personal desire to unpack questions about class, education, and social mobility. My DPhil, entitled “Working-class women and higher education in Britain, 1965-1975”, asks how working-class women experienced higher education in these years, and how their experiences fit in to their broader life histories. In this period, the tripartite system purported to improve working-class access to the grammar schools, while the Robbins Report of 1963 saw a substantial increase in higher education places. In an era often characterised as the ‘golden age’ of social mobility, I look to explore how women who were educational ‘successes’ experienced this success, and what effect it had on their later lives. Thus, my DPhil is a history of post-war social change in the era of the Education Act, the Robbins Report, and the women’s liberation movement; but it’s also a history of class, the self, and how it felt to be one of the ‘scholarship girls’ in a world that was centred around ‘meritocracy’.

To answer these questions, I’ve had the privilege of carrying out oral history interviews with a cohort of women who were working-class students at universities, teacher training, art and drama colleges in the 1960s and 1970s. One of the joys of oral history, beyond the obvious benefit—to the great jealousy of my non-modernist friends—of being able to ask your subject anything you like, is the way that each interview goes somewhere unexpected. I have heard an eclectic array of stories: of hiding hideous grammar school hats on the school bus; trudging around muddy, half-built university campuses in wellies; skipping exams to make cheesecloth skirts and anti-apartheid banners; setting up campus nurseries; moving to Kenya, to Germany, to Bulgaria; meeting Allen Ginsberg. As I explore my central questions of class, social mobility, and education, a full, vivid world is emerging around them.

And Oxford has been an exhilarating place to carry out this research. While Oxford is perhaps particularly known for its strengths in more traditional approaches to history, my work has consistently been enlightened and supported by a community of scholars working on gender, class, race, and other topics, particularly by my supervisor, Professor Selina Todd, and fellow researchers at the Centre for Gender, Identity and Subjectivity (CGIS) and TORCH’s Women in the Humanities programme. I’ve had the opportunity to take part in reading groups, meet and talk with visiting scholars, and present my research to a supportive and curious community dedicated to asking questions of history from all angles. There are few things more exciting—and exasperating—than leaving a seminar questioning almost everything you thought you knew.

These communities have also led to new opportunities. In 2015, two doctoral students, Olivia Robinson and Alison Moulds, began a podcast, Women in Oxford’s History, generously supported by TORCH. The podcast explores the lives of overlooked women in Oxford’s history, both ‘town’ and ‘gown’. I joined the team of podcast researchers, and this summer became a co-producer. This has meant mastering a whole range of new skills—script writing, sound editing, production—and also the opportunity to see Oxford in a new light. Last month, I visited the archive at St. Anne’s college to research a podcast episode about Merze Tate, the first African American woman to graduate from the University. Sat leafing through her student file—a yellowing folder crammed full of courteous typewritten correspondence—I felt the same excitement I’d felt reading my great uncle’s autobiography a decade ago. No matter how long I’ve been working on history, or how many archives I’ve been to, being able to trace the curl of somebody’s handwriting under my fingertips never fails to excite me.

As I get stuck in to the third year of my DPhil, the day that I first read my great uncle’s notebook seems a very long time ago. Doubtless, in years to come, these privileged years at Oxford will also feel a lifetime away. But I know that I will continue to benefit from the experiences I have had here for the rest of my academic career, and I am excited to continue researching and writing about the lives of men and women who, like my great-uncle, Merze Tate, and the women I’ve interviewed, can add so much colour and so many questions to our understanding of history, how we research it, and who it belongs to.

-Bethany White

Dphil candidate in History

Artistic License

Bethany has recently written a series of articles about the exciting and impressive research taking place in the Humanities Division.