Who was the Schools Action Union For?

Shona Roberts is a recent University of Reading History and Politics Graduate, with a keen interest in the development of social and political movements.

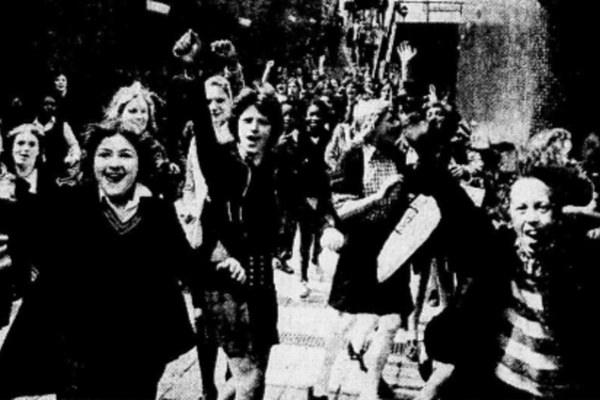

Ten thousand school children protesting in London’s Trafalgar Square is something of a Prime Minister’s nightmare. Yet, in May 1972 this nightmare was a reality for Edward Heath’s Conservative government, to such an extent he commissioned MI5 to set up a network of infiltrating agents to assess whether this posed a national security risk. The Schools Action Union (SAU) had called upon all of their ‘comrades’ a week earlier to stand up for what they believed in and challenge the tyrannical dictatorship of the Headmaster and his bourgeois controllers.[1] According to the SAU the role of the Headmaster ‘conditioned [students] to accept the dictatorship of the head in school so that we’ll accept the sole authority of the boss in the factory’.[2] This begs the question who were the SAU and what had led them to this point? This blog will first contextualise the SAU and their demands before focusing upon the experiences of the young female members of the SAU in a bid to assess the extent to which inequalities within the movement persisted as the result of gendered inequalities.

Figure 1: ‘A Days ‘Work’ for a Schoolboy Wrecker Who Agrees His Demos Mess Up His Exams’, The Daily Mail, 5th May 1972, pp.12-3

On 4th January 1969, members of the Manchester Secondary School Union, the Leeds Schools Action Group, the Swansea Union of Progressive Students and the South London Free Schools Campaign were all brought together at a national conference held by the London Secondary School Student Union.[3] As part of this conference, a resolution was passed to be hereafter known as the Schools Action Union, with each pre-existing group represented at the conference becoming a local branch of the Union. It was also agreed that the Vanguard publication created by the London Secondary School Student Union was to become the official publication for the entire SAU movement, with members of all branches encouraged to send in submissions, comments on any submissions and queries. This conference was the creation of Tricia Jaffe, an eighteen-year-old girl who had spent the previous year living in France and playing witness to the student-power protests. It is in this context that Edward Heath, alongside Margaret Thatcher (then Secretary of State for Education and Science), embarked on a policy of ignoring the issues presented by the SAU until the movement officially disbanded, which was not to be until 1974.[4]

It was at this same conference that each pre-existing branch contributed to and agreed upon a series of eight comprehensive demands which were as follows:

- ‘The freedom of speech and political activity; the right to organise a general student assembly inside schools; no censorship of school clubs, magazines and societies’.

- ‘Effective democratic control of the school by an elected school council made up of representatives of students, teachers and all staff’;

- ‘The abolition of all exams and grading; of the prefect system and school uniform; of all religious instruction and acts of worship; of all military training and compulsory physical education in schools’;

- ‘The abolition of all corporal and autocratic forms of punishment. A code of self-discipline to be decided by the general assembly of all students and staff’;

- ‘A free, non-segregated, non-streamed (by class, race or sex) comprehensive educational system, excluding all other types of school’;

- ‘Schools universities and colleges to become local evening centres of educational and cultural activity and discussion, run by worker/student/teacher alliances’;

- ‘Full maintenance grants to all receiving full-time education over minimum school leaving age’;

- ‘A much higher priority nationally for education; a general increase in government expenditure including more pay for teachers’.[5]

Over the course of 1969-74, the SAU’s publications suggest that they often changed their demands and priorities to match current member or societal views, such as the demand for the ending of compulsory religious education, which became increasingly important throughout the period.[6]

In the initial stage of my research, I focused my attention on digitalised national newspaper articles that explicitly mentioned the SAU between the years 1969 and 1974. These 153 articles not only provided some much-needed context but revealed a stark contrast between how the SAU saw themselves and their mission, and how the mainstream media saw them and their goals.

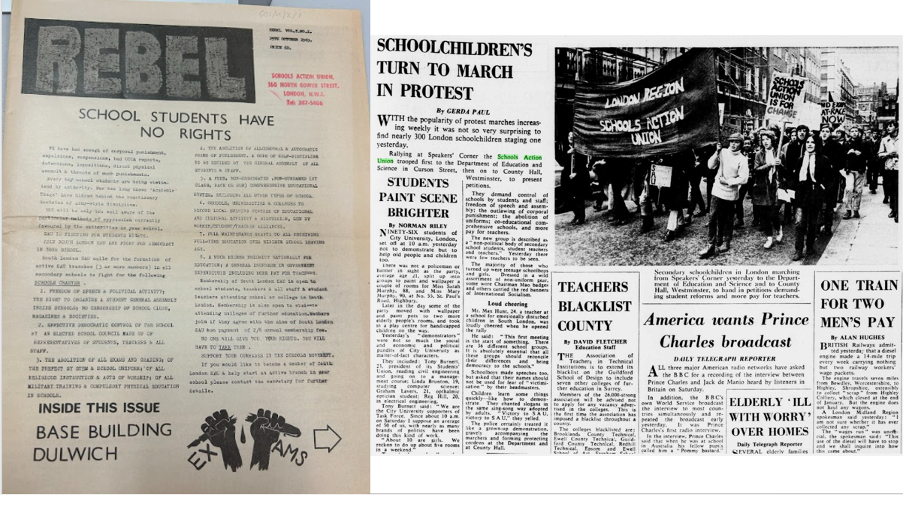

In contrast to the SAU’s eight demands, as outlined above, The Daily Telegraph in 1969 reported on only the following six demands:

‘Demand control of schools by students and staff; freedom of speech and assembly; the outlawing of corporal punishment; the abolition of uniforms; co-educational comprehensive schools, and more pay for teachers’.[7]

Figure 2: Demands – In the words of the SAU and the Mainstream Media: ‘School Students Have No Rights’, Rebel, Vol 1, Issue 1 (1969); G. Paul, ‘Schoolchildren’s Turn to March in Protest’, The Daily Telegraph, Issue 35410, (1969) p.15

These six demands, and not the eight demands outlined by the SAU in their own media publications, were repeated by The Daily Telegraph in every other newspaper article on the subject of the SAU, as well as other mainstream newspapers such as the Daily Mail, and the Daily Mirror.[8] By choosing to only list six out of the eight demands, as well as excluding any mention of the SAU’s discussions in their magazines and pamphlets of gender inequality, the mainstream media limited the attractiveness of the SAU to potential members. The Vanguard and Rebel publications had limited circulations and cost 3d before rising to 6d by the fourth issues.[9] This restricted the group’s ability to communicate what they wanted to who they wanted.

The SAU had a reputation amongst contemporaries for being an exclusive, elite and male group. Such a reputation was reinforced by the media’s repeated reporting on the successful SAU branches that had been established at Harrow and Eton.[10] The media did not report on any successful branches established at all-girls schools, instead focusing on how branches at all-boys schools would rescue those at all-girls schools from their tyrannical headteachers.[11]

Some newspaper reports also misrepresented the SAU demonstrations. The Daily Mirror in their reports of SAU activity were far more likely than the Daily Mail to copy the language used by leaders of the movement. For example, the Daily Mirror would refer to SAU members as ‘comrades’ whereas the Daily Mail insisted on referring to members as ‘schoolboys’.[12] By making the protestors appear juvenile and male, this language created an image of a movement that was exclusive, unorganised, and likely to be short lived. Such language is in complete contrast to the language members of the SAU used to describe themselves and the issues they cared about.

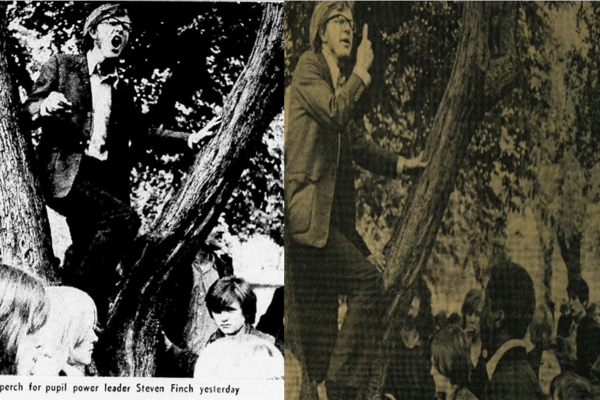

The mocking of the SAU by the right-leaning mainstream press continued in the images chosen to accompany the written text, as shown in Figure Three below. These two images show Stephen Finch, aged 17, leader of the SAU, giving a speech from a tree as part of an organised strike on May 8th 1972. The image on the left was published in right-leaning Daily Mail article titled ‘Pupil Power Leader Arrested in Strike Demo’; the image on the right, on the other hand, has been taken from a newspaper article written by the left-leaning Daily Mirror titled ‘Pupil Power Leader is Held’.[13] [14] In the image on the left, Finch is shown to be shouting to a small crowd of around eight individuals who are all looking in the opposite direction to where he is talking. This creates the impression that Finch was simply talking for his own benefit and that the crowd were humouring him for the sake of a day off school. This allowed the Daily Mail to continue its reporting that the SAU was so outrageous that not even those in the same generation as its members were willing to give it the time of day. This is especially true of the two girls in the bottom left of the image who appear to be walking past Finch in his tree. This enabled the Daily Mail to present the SAU as no place for young girls.

Figure 3: Stephen Finch According to the Left and Right-Leaning Mainstream Media. The Daily Mail, ‘Pupil Power Leader Arrested in Strike Demo’, (May 1972); The Daily Mirror, ‘Pupil Power Leader is Held’, (May 1972)

The Daily Mirror image of the same event created a different impression. Finch is pictured giving a civilised speech to a mass crowd of young people, who are giving him their undivided attention, thus drawing parallels to how Finch would have been received if he was an elected politician. The image also shows Bobbi Labi (the then Press Secretary of the SAU) located just behind the tree trunk, looking up to Finch in such a way that also suggests he too was giving Finch all his attention. This shows a cohesiveness of the movement that the Daily Mail and other right-leaning press did not want to acknowledge the SAU had.

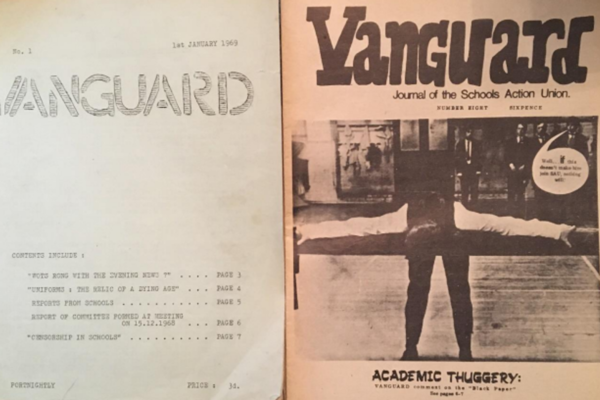

It is important to note that the SAU, like every political movement, did not operate within a vacuum, thus the movement was heavily connected to other contemporary movements and events. In an early addition of Vanguard, the SAU increased the price per issue from 3d to 6d as a result of surprising printing costs and the realisation that they would like to find a permanent space to act as the SAU’s headquarters.[15] In a matter of months, the SAU moved into a shared office space in Euston’s North Gower Street. This office was shared with Agitpop, a self-proclaimed ‘communications service for the Left, working to build up distribution channels for pamphlets, news and contacts’, who began working with the SAU to improve the quality of their communications.[16] Figure Four is a side-by-side comparison of the first issue of Vanguard published using a school copybook, and the eighth issue of Vanguard, which had transformed into a format more consistent with other activist publications.

Figure 4: A Side By Side Comparison of Vanguard, the SAU’s chief media publication, before and after the creation of a working relationship with Agitpop. The SAU, Vanguard, Vol 1, (1969) p.1 ; The SAU, Vanguard, Vol 8 (1969)

Agitpop brought the SAU into the forefront of contemporary political movements due to also producing media for the Gay Liberation Front and the Women’s Liberation Movement. That being said, however, the connections between the latter and the SAU can arguably be traced to the origins of the SAU. At the very first SAU Conference held in January 1969 it was agreed that at least one demand should be focused on appeasing teachers in a bid to get them on side and increase the likelihood of success.[17] Due to this, the SAU initially called upon their comrades to support the teachers’ strikes in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Such strikes have since been pinpointed by historians as one of the origins of the Women's Liberation Movement.[18] This therefore provides a potential explanation as to why both movements believed that consciousness raising, as it was coined in the second wave feminist movement, and the sharing of lived experiences was the solution to societal problems.

So with all this in mind, what was it like to be a young girl in the SAU? Internal documents and records suggest that female comrades accounted for over half the total membership.[19] To test this hypothesis I visited the Modern Records Centre as part of the University of Warwick to read letters that had been written to the London, Coventry and Manchester branches of the SAU. Some of these letters mirrored the themes of those published by both the SAU in their Vanguard and Rebel magazines, as well as those published by The Daily Telegraph and other mainstream press. These letters focused on fear of parental discovery, which appeared to be a universal struggle irrespective of gender. Joining the SAU had high opportunity costs as members were often publicly expelled from school and prevented from going to the universities of their choosing.

Figure 5: The Issue of Women’s Rights According to SAU Members, The SAU, Rebel, Volume 2, (1969) pp. 2-3

Figure five, from Rebel magazine, shows how some members of the movement did engage with the issue of gender equality and social equity. Through the writing of such articles, members of the Union were encouraged to voice their concerns surrounding their school, the education system and, crucially, society. Such opportunities to write may have helped female members of the Union realise that the issues they were facing at school, such as corporal punishment or the number of exams, would only be experienced temporarily, in contrast to the sustained inequalities that denied them rights as women. It is no stretch of the imagination to suggest that the lasting legacy of the SAU still endures as a result of its ability to act as a feeder to other social movements happening concurrently, namely the Women’s Liberation Movement.

That being said, however, one clear difference between the genders was the perceived importance of the different demands. Boys tended to write to the SAU to report instances of corporal punishment or complain of compulsory physical education. Girls, on the other hand, wrote to explain how compulsory school uniforms created problems for their families due to the yearly need for replacement and high cost, or how they were excluded from certain clubs and societies at school due to the fact that they were meant for boys. However, these girls’ concerns were not reflected in demands made by the SAU. In fact, the only two branches of the SAU who focused their efforts on attempting to change their school uniform were the Harrow and Eton branches. This highlights that although girls might have made up the majority of comrades within the SAU, concerns that were primarily expressed by girls were not listened to by the national organisation. This can be furthered by the fact that throughout the five years of the SAU, they only had one girl in a position of public leadership.

Considering this, the answer to the question of who was the SAU for is hardly simple. In principle, the SAU was created to benefit all school-aged children due to the group’s dedication to challenge pre-existing structures of inequality and injustice. However, the prominent members and leaders of the SAU tended to be white males from middle-class backgrounds. The constant portrayal in the media of the SAU as a privately educated boy’s playground, through the repeated press coverage of the Harrow and Eton factions, challenged the group’s narrative that the SAU was open to everyone, particularly young girls from more working-class backgrounds.

[1] S. Finch et al., ‘Saturday Review Column’, The Times, (June 1972) p.8

[2] S. Finch et al., ‘Saturday Review Column’, The Times, (June 1972) p.8

[3] The SAU, ‘Editorial’, Vanguard, Issue 1 (1969) p.2

[4] Hansard, ‘Schools Action Union’, Vol 838 (15 June 1972), https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/1972-06-15/debates/77e6181b-cab4-4aba-a6f3-b948f1ded81c/SchoolsActionUnion?highlight=%22schools%20action%20union%22#contribution-ccc16596-6dc8-492d-a5e9-cade97c3124f

[5] The SAU, Rebel, Vol 1, Issue 1 (1969) Rebel, Vol 1, Issue 1 (1969) p.1

[6] Hemel Hempstead SAU, ‘Religious Education’, Red Herring, Vol 2, p.5

[7] G. Paul, ‘School Children’s Turn to March in Protest, The Daily Telegraph, (3 March 1969), p.X

[8] See: The Times, ‘250 Children March in Protest’, The Times, Issue 57499, (1969) p.3 ; S. Wilkins, ‘Harrow Boys Sign up for Pupil Power’, Daily Mail, Issue 22758, (1969) p.3 ; J. Izbicki, ‘Militant Group at Harrow’, The Daily Telegraph, Issue 35515, (1969), p.24 ; The Illustrated London News, ‘Should Pupils Have a Voice?’, The Illustrated London News, Issue 6796, (1969), p.14

[9] Magazines could only be purchased from an official SAU-approved seller, or through the completion of a subscription application form from within the magazine.

[10] See: The Times, ‘Eton Targets for Militants’, The Times, Issue 57610 (1969) p.12 ; J. Killigrew, ‘Rebellion in the Classroom’, The Sunday Times, Issue 7625 (1969) p.9 ; R. Nash, ‘The Poor Little Rich Boys’, Daily Mail, Issue 22830, (1969) p.14

[11] ‘A Days ‘Work’ for a Schoolboy Wrecker Who Agrees His Demos Mess Up His Exams’, The Daily Mail, 5th May 1972, pp.12-3

[12] The Daily Mirror, ‘Freedom March by Children’, The Daily Mirror, Issue 20692, (1969) p.5 ; Daily Mail, ‘Schoolboys’ Strike’, The Daily Mail, Issue 22860, (1969) p.9

[13] Daily Mail, ‘Pupil Power Leader Arrested in Strike Demo’, The Daily Mail, Issue 23629, (1972) pp.16-7

[14] M. Dowdney, ‘Pupil Power Leader is Held’, Daily Mirror, Issue 21251, (1972) p.5

[15] The SAU, ‘Editorial’, Vanguard, Vol 3, (1969) p.2

[16] Marxist Studies, Volume 2 (1969) p.33

[17] The SAU, ‘Editorial’, Vanguard, Issue 1 (1969) p.2

[18] S. Bruley, ‘It didn’t just come out of nowhere did it?: The Origins of the Women’s Liberation Movement in 1960s Britain’, Oral History, 45:1, (2017) pp. 67-78

[19] O. G. Emmerson, Childhood and the Emotion of Corporal Punishment in Britain: 1938-1986, (unpublished PhD thesis, Sussex, 2019) p.243