“This Boy is Really a Girl!”: Youth Cross-Dressing in late Victorian and Edwardian Britain

Hannah Stovin is a second year PhD student at Mansfield College, under the supervision of Prof. Christina de Bellaigue and Prof. Matt Cook. Her doctoral research is an examination of the social, cultural and medical understandings of the ‘queer child’ in Victorian and Edwardian Britain. She holds a BA in History from the University of Oxford and an MPhil in Modern British History from the University of Cambridge. Prior to undertaking the DPhil, she also worked as a Trainee Archive Assistant at the National Gallery.

Figure 1: "Masquerading as a Boy." The Evening Telegraph and Star, 15 February 1896, p. 2

Published on the 19th March 1889 in The Daily Telegraph, an unidentified columnist wrote about the supposedly new and alarming figure of the ‘girl-boy’:

“… Worthy people who hold the unnecessarily sensational in horror, are devoutly hoping that the revived craze among girls for masquerading in boys’ clothes will not develop, as it threatens to do, to the proportion of an epidemic

…

Perhaps, medical men may have to speculate whether this propensity among girls for assuming the garments of the opposite sex is not a practically novel form of hysteria”

In evidence of the widespread nature of this so-called “epidemic”, the author went on to describe how “another cheap and equivocal Rosalind” had just turned up in Dublin. A young man, ostensibly a boy of fourteen, had been recently sent to Kilmainham Goal for fourteen days after being found to be a wandering Vagrant. At the prison this “seeming lad” turned out to be a young woman, and was consequently removed to the gaol for female prisoners at Grangeroman. Here the individual was “dressed in the garments of her own sex”, an experience that the journalist acknowledges, made the prisoner “look and feel intensely uncomfortable”. Upon questioning, the prisoner proclaimed no wrong doing and explained to the officers that, for “some mysterious reason”, they had always been brought up as a boy, and had never answered to any other name than that of “John Bradley”.[1]

As this panicked editorial suggests, the figure of the “girl-boy” – a girl masquerading in boys’ attire – was a pervasive and evocative figure within late nineteenth and early twentieth century Britain. My sweep of digitised newspaper repositories has unearthed at least 51 reported cases of ‘girls’ dressing as ‘boys’ between 1867 and 1919 in the British Isles alone. These stories were widely circulated, picked up by both national and regional papers, and often republished with increasingly sensational details that lent them a larger-than-life quality. When international reportage from the United States and Europe are taken into account, the cultural presence of this figure becomes even more pronounced.

Similar to how the ‘female husband’ has been acknowledged as a cultural figure, in this blog, I want to make a similar case for the ‘youthful masquerader’- as both a recurring character of late nineteenth century public discourse and indeed, of late nineteenth century life.[1] These figures existed in the pages of newspapers but this also means they existed in the streets of late Victorian Britain. The prominence of this as a cultural depiction suggests not only a world in which gender norms were not only subject to sustained debate but also one where individuals came face to face with youthful gender crossing on a somewhat regular basis.

Whilst historians have extensively explored the category of the female cross-dresser in this period, this has largely been under the broad label of “cross dressing women”.[2] Such a categorisation implicitly presumes or bestows adulthood. This, however, elides the fact that the majority of these individuals were extremely young and that the terminology of girl/boy was often used to describe them. Indeed such vocabulary was often utilised even when they weren’t particularly youthful in terms of their ‘real' age. By consciously recognising these individuals as young, I also want to suggest that we can better understand both their motivations and the responses elicited by such behaviours. Specifically, I argue that their assumed ‘childishness’ was used as a means by which to legitimate and in some ways, sanction, their gender mutability. In sum, girlishness could operate as an alibi. The trope of the ‘girl-boy’ therefore, I argue, suggests something provocative about the perceived relationship between youth and gender in this period.

In the rest of this blog post, I want to introduce a brief case study that both exemplifies this ‘phenomenon’ and specifically highlights the importance of viewing these figures through the lens of childhood:

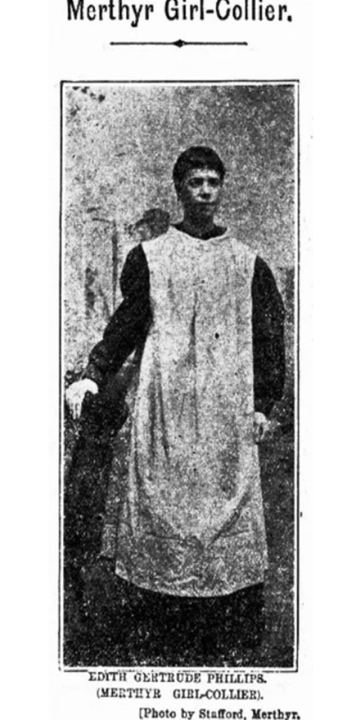

Figure 2 : “Merthyr Girl-Collier." Evening Express (Cardiff), 4th November 1901, p. 4.

Edith Gertrude Philips: “A Welsh Rosalind!”[1]

In 1901, fifteen-year-old Edith Gertrude Phillips left their home in the Welsh village of Abercanaid. Professedly upset at their mother’s abusive conduct, “the girl secretly donned masculine attire” and took up a new identity as a boy. Renting a room in a local lodging house, they took up work in a local mine as the pit boy of a collier. This ruse, however only lasted a week; their conduct quickly falling under suspicion and their original identity being publicly uncovered in the local press.

Unusually for such incidents, Philips gave a personal account of their escapade and this report was reprinted by various local newspapers:

“Towards dinner- time on Monday, when the coast was clear, I went into the back garden and put on a shirt and an old suit of clothes belonging to my brother Joseph, which were hanging out on some bushes, and cut my hair short with a pair of scissors. I threw my own clothes into the canal, and went for a walk round the Cwn pit” [2]

Despite the clearly meticulous and determined nature of the escapade, the incident was largely presented as humorous: “Collier Girl’s Adventure!”, “Welsh Maiden’s Remarkable Escapade At Merthyr” and “A Welsh Rosalind!” to give but a few of the newspaper headlines.[3] These captions clearly cast Phillips’s behaviour as a youthful adventure rather than a meaningful or subversive act. Whilst Philips may themselves have conceived of it as such, this press narrative rendered it safely entertaining for a readership that might otherwise view such behaviours with suspicion. Philips was ostensibly a ‘young girl’ and this transgression was simply a product of a childish – or more specifically, girlish – desire for freedom and adventure.

The clear permissibility of this behaviour is reiterated in the rallying of the local community in support of Phillips. Once the news of the incident broke, the Colliers of South Wales launched a support fund for the child- one that eventually raised over £30 in donations. Prominent supporters included David Alfred Thomas, the MP for Merthyr Tydfil, the Cardiff Evening Express, and the Plymouth Colliery Men. Driven by the belief that “so brave a character should be guarded and cared for in the outset of her young life”, the fund was intended to provide clothing, housing and education for Phillips until the age of 21.[4] Far from a pariah or embarrassment, Philips was elevated to the status of local icon.

Whilst the details of the case of Edith Phillips clearly makes it unique, in a wider sense, it was far from exceptional. Whilst a single incident could be discussed in this blog, instances of ‘girls masquerading as boys’ appeared regularly within the late nineteenth century press. These episodes of youthful gender masquerade were not isolated curiosities but recurring flashpoints; flashpoints which reveal much about the understanding of both gender and childhood in this period. Specifically, I argue that they suggest a belief system which permitted a remarkable degree of gender fluidity - though only within the bounds of youth. Queer/trans histories and the history of childhood are fields that have too often operated in parallel rather than in dialogue. The figure of the girl-boy reveals, however, that gender fluidity is not a solely adult phenomenon, but a historically rooted, complex, and deeply human experience that has often played out vividly in the lives – and bodies – of young people.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

"Collier Girl’s Adventure." Norfolk News, 12 October 1901.

"Girl as a Boy: Welsh Maiden’s Remarkable Escapade at Merthyr." Morning Leader, 7 October 1901.

"London Day by Day." The Daily Telegraph, 19 March 1889.

"Masquerading as a Boy." The Evening Telegraph and Star, 15 February 1896.

"The Merthyr Girl-Collier." Evening Express (Cardiff), 17th October 1901.

"Merthyr Girl-Collier." Evening Express (Cardiff), 4th November 1901.

"A Welsh Rosalind. Young Girl's Escapade as a Colliery "Boy.". Radnorshire Standard, 9 October 1901.

Secondary Sources

Hager, Lisa. "A Case for a Trans Studies Turn in Victorian Studies: “Female Husbands” of the Nineteenth Century." Victorian review 44, no. 1 (2018): 37-54. https://doi.org/10.1353/vcr.2018.0008.

Hindmarch-Watson, Katie. "Lois Schwich, the Female Errand Boy: Narratives of Female Cross-Dressing in Late-Victorian London." GLQ 14, no. 1 (2008): 69-98. https://doi.org/10.1215/10642684-2007-023.

Manion, Jen. Female Husbands: A Trans History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020.

Oram, Alison. Her Husband Was a Woman!: Women's Gender-Crossing in Modern British Popular Culture. London: Routledge, 2007.

Shopland, Norena. Forbidden Lives: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Stories from Wales. Bridgend: Seren, 2017.

———. A History of Women in Men's Clothes : From Cross-Dressing to Empowerment. Barnsley: Pen & Sword History, 2021.

[1] This case has also been outlined by Norena Shopland. See: Norena Shopland, Forbidden lives : lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender stories from Wales (Bridgend: Seren, 2017), Chapter 7.

[2] "Girl as a Boy: Welsh Maiden’s Remarkable Escapade at Merthyr," Morning Leader 7 October 1901.

[3] "Collier Girl’s Adventure," Norfolk News 12 October 1901; "Girl as a Boy: Welsh Maiden’s Remarkable Escapade at Merthyr."; "A Welsh Rosalind. Young Girl's Escapade As A Colliery "Boy.," Radnorshire Standard 9 October 1901.

[4] "The Merthyr Girl-Collier," Evening Express (Cardiff), 17th October 1901, p. 3.

[1] For more on the female husband see: Jen Manion, Female Husbands : A Trans History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020); Lisa Hager, "A Case for a Trans Studies Turn in Victorian Studies: “Female Husbands” of the Nineteenth Century," Victorian review 44, no. 1 (2018): pp. 37-54, https://doi.org/10.1353/vcr.2018.0008.

[2] See: Norena Shopland, A history of women in men's clothes : from cross-dressing to empowerment (Barnsley: Pen & Sword History, 2021); Alison Oram, Her husband was a woman! : women's gender-crossing in modern British popular culture (London: Routledge, 2007); Katie Hindmarch-Watson, "Lois Schwich, the Female Errand Boy: Narratives of Female Cross-Dressing in Late-Victorian London," GLQ 14, no. 1 (2008), https://doi.org/10.1215/10642684-2007-023.

[1] "London Day by Day," The Daily Telegraph 19 March 1889, p. 5.