The role of the lay elite in the development of early medieval Christian kingship

Katie Duthie has just finished her second year studying history at The University of Cambridge. She has a specific interest in early ‘Anglo-Saxon’ history, focusing her final-year dissertation on Polities and Communities in Pre-Viking England. She is particularly interested in the use of archaeological sources by historians, framing her dissertation around an analysis of Fleam’s Dyke and Devil’s Dyke in Cambridgeshire. Taking part in the UNIQ+ research internship supervised by Dr Conor O’Brien, this blog represents one part of her summer project. Outside academics, Katie enjoys cycling and running, alongside playing the violin in various orchestras.

Scholarship concerning the development of Christian kingship has been beset by a form of tunnel vision: focusing entirely on the role of high ecclesiasts and kings, historians from the eighth to the twentieth century (from Bede to Stenton) continually overlooked the role of others in the rise of sacred rulership. The role of the lay elite was made invisible, with only the gradual secularisation of Western society and the demise of purely ‘high’ political history allowing this section of society to be analysed. Following Damian Tyler’s recent focus on the need for elite support in the development of Christian kingship, this blog will decentralise the importance of kings in the development of sacred rulership.[1] Through a series of Anglo-Saxon case studies, the importance of the lay elite in early medieval politics and religion will be advanced. Policing the relationships between ruler and ruled, kingdom and continent, secular and sacred, the lay elite provided the support and connections that were essential to the development and spread of Christian kingship in the early Middle Ages.

The figure of Raedwald – an early seventh-century ruler of East Anglia, and potentially the figure buried at the magnificent ship burial of Sutton Hoo – presents the essential nature of lay support in the development of Christian rulership. From Bede’s Ecclesiastical History (written c.731), a vision of Raedwald serving both Christ and paganism emerges.[2] Bede asserts that even after formal conversion, the East Anglian ruler held a temple which featured one altar for Christian ritual and another for pagan sacrifice. Raedwald’s support appears to have been divided between the two cults.

The archaeological evidence of the Sutton Hoo burial corroborates this image. The rites witnessed at this site are typical of a pagan burial, featuring the use of a ship, a mass of grave goods, and iconography of dragons and other supernatural figures (such as the small figure standing on the rump of one of the horses) adorning the famous helmet. This is contrasted by other features which appear decidedly ‘Christian’. A set of three silver bowls and two spoons were found at the head of the grave, suggesting that the mourners viewed these as holding special importance among the burial goods. This is significant given that the silverware – originally created in the eastern Mediterranean and probably brought to East Anglia through Frankish sources – features numerous Christian motifs. The three bowls feature decorative crosses, and the spoons are embossed individually with ‘Saulos’ and ‘Paulos’ which has previously been interpreted as a reference to Saint Paul the Apostle. Werner has likewise suggested that the gold buckle found at this burial was a Christian ‘belt-reliquary’.[3]

Figure 1. Replica of the helmet made by the Royal Armouries, The British Museum. Photo by Steven Zucker. Reproduced from: https://smarthistory.org/the-sutton-hoo-helmet/

Bede argued that it was the influence of Raedwald’s wife and his ‘evil teachers’ that left him unable to fully commit to Christianity. Upon his return home from the court of Aethelberht of Kent, where he had formally converted to Christianity, he was ‘seduced’ by these nobles (his wife and teachers) to place the pagan and Christian altars in the same temple. Although Bede’s narrative of Raedwald being controlled by his wife can be seen as a particularly gendered assessment of a king who did not adhere to Bede’s perception of strong rulership, it also hints at the importance of the political elite in the formation of Christian rule. Without the support of his queen and the ‘evil teachers’, who were likely noble counsellors, Raedwald could not commit to the full Christianisation of his kingship. Within the socio-political world of early Anglo-Saxon England, based on mutual obligation and alliance, Raedwald’s only partial commitment to Christianity derived from a lack of elite support for the wider process of Christianisation.

Figure 2. Silver bowls and spoons of eastern Mediterranean provenance found at the Sutton Hoo burial. Held by The British Museum. Reproduced from: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/H_1939-1010-80.

Similarly, Bede’s story of the conversion of Edwin of Northumbria presents the necessity of gaining elite support before committing to a new religion. Bede describes Edwin as seeking advice from nobles on the matter of formal conversion at least three times. After what seems to have been a lack of support from these men, it was only upon pressure from Bishop Paulinus and letters from Pope Boniface, alongside consulting his counsellors again, that Edwin committed to full baptism. In recounting the conversion of Sigeberht of the East Saxons to Christianity in the mid-seventh century, Bede argued that the king undertook baptism at the Bernician court in c.653 only after a long process of gaining support and consensus from the lay elite through counsel:

‘[A]t last, supported by the consent of his friends, he believed. He took counsel with his followers and, after he had addressed them, they all agreed to accept the faith and so he was baptized with them’.[4]

Support from the political elite was crucial in the development of Christian rule.

The power of the lay elite also had a much less localised effect: the effect of exile. Providing the cornerstone of a ruler’s support, it was often disillusionment among the elite that sent Anglo-Saxon rulers into continental exile. The ninth-century case of Ecgberht of Wessex (r.802-839) is evidence of this. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (written at the end of the ninth century), notes that before his accession to the throne of Wessex, Ecgberht had been forced to flee in exile to Francia. This flight appears to have been in response to a shift in allegiance of the West Saxon elites towards Beorthic (with the help of Offa of Mercia) in the aftermath of the death of King Brihtric in 802. Without elite support, and pitted against the powerful rulership of Offa of Mercia, Ecgberht was forced to flee. It was to this period in exile with the Carolingians that William of Malmesbury (writing in the twelfth century) attributed Ecgberht’s skills in ‘the art of governance’.[5] Malmesbury suggests that Ecgberht’s rulership was shaped by the models he had seen while ousted from his kingdom by neighbouring kings and laity alike.

Moments of exile forged links between neighbouring regions, actively spreading ideas of Christian rulership. There are two surviving accounts of Eardwulf’s accession to the Northumbrian throne in 796: that of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and that of the York Annals. Both show an elaborate kingmaking ceremony in the presence of the four highest clergymen of Northumbria at the time, including the Archbishop of York, Eanbald. As Joanna Story has noted, this is the first time that a specific ‘king-making’ ceremony is seen in relation to Northumbria in the surviving record.[6] The vocabulary used to describe this ceremony bears close comparison to the description of the Frankish king, Pippin’s, anointment in 751.[7] This comparison is particularly significant given that royal anointing seems to have developed in Francia primarily in the interest of the lay elite, enabling the Carolingians to set themselves above other elite rivals through the use of Christianity.[8] It was Eardwulf’s connection with the Carolingians, partly formed through his exile to the continent in 806, and partly through the mission of bishops sent to England by Pope Hadrian in 786, that led him to use royal anointing in the typically Frankish way – as a way of gaining elite support upon his accession. The importance of the lay elite in ecclesiastical decisions (including, perhaps, the decision to commit to an anointing ceremony) can be seen in the surviving document of the bishops’ mission to England, which was witnessed by ‘ealdormen’ (lay nobles) as well as bishops, priests, and abbots.

Meier and Patzold have recently reminded scholars of the importance of disconnection, as well as connection in the early medieval world, responding to the continual highlighting of connectivity and communication that became widespread after the 1990s boom of ‘global’ approaches.[9] However, in relation to Anglo-Frankish connectivity, the link presented in present-day scholarship does not appear to be overstated. Material presentations of Christian rulership, such as the silverware of Sutton Hoo, flooded in from Frankish sources, and the letters and annals of the time attest to great connectivity between rulers in these realms. Likewise, exile not only affected rulers (and potential rulers) themselves but had a direct effect on the laity. With both Bede and Beowulf presenting the likelihood of these individuals travelling with a comitatus of political elites, the noble laity would have come into direct contact with Christian influences at the same time as their superiors did. Cross-channel connection – here analysed through case studies of exile – was a significant force in progressing models and understandings of Christianisation. Pushing rulers into exile and following them to the continent, the lay elite were an important part of this process.

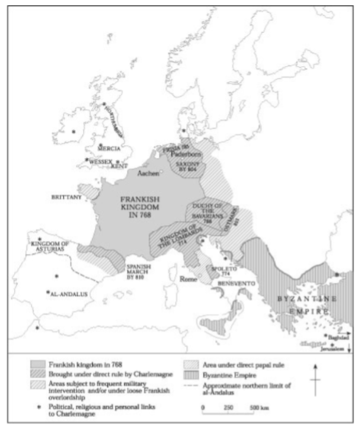

Figure 3. Map of Anglo-Frankish connections. Reproduced from Julia Smith, Europe After Rome: A New Cultural History, 500-1000 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), p.270.

Robert Markus argued that late Antiquity was differentiated from the early Middle Ages by a process of ‘de-secularization’; a process by which the space for religiously neutral institutions and identities slowly disappeared.[10] While it was possible in late Antiquity to have purely ‘secular’ institutions, by the time of Pope Gregory the Great, the scholar argued that this was no longer the case.[11] Markus argued that this ‘de-secularization’ was the effect of ‘the Church’ alone, in turn presenting the convergence between the secular and the non-secular as beginning only after conversion to Christianity.

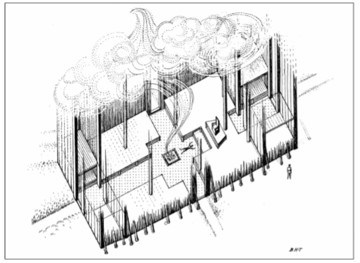

An analysis of archaeological data from pre-Christian Anglo-Saxon ‘England’, however, questions these conclusions. The process of ‘de-secularization’ appears to have begun before the conversion to Christianity, and the long process of ‘de-secularization’ involved a much broader section of Anglo-Saxon society than simply ‘the Church’. At the pre-Christian hall site of Yeavering, little distinction between secular and non-secular authority is seen. As Jenny Walker notes, the archaeological comparisons between those halls at Yeavering which would be described as ‘secular’ (e.g. A2), and those that would be described as ‘religious’ (D2- pagan temple) are so similar that they must have been linked in function and ideology.[12] Similar halls in Scandinavia, for example Borg in Lofoten, feature both ritual and secular spaces within the same hall. The chief or king who was sitting on the throne in building A2 at Yeavering (seen in the interpretative image below) held a position that was inherently bound to their sacred identity.

The sixth-century Bidford-on-Avon burial of a woman equipped with brooches, pendants, beads, bronze tubes, and a knife provides evidence for a class of female Anglo-Saxon shamans. Likely identified as lay persons with specific spiritual or healing properties, non-Christian individuals such as these shamans would have been important elements in the convergence of the secular and the sacred before the conversion to Christianity. Shaping the relationship between the secular and the sacred, pre-conversion lay elites were just as significant as ‘the Church’ in the development of sacred kingship.

Figure 4. Interpretive image of building A2 at Yeavering. Reproduced from Signals of belief in early England: Anglo-Saxon paganism revisited, eds., Martin Carver, Alex Sanmark, and Sarah Semple, p.90.

Providing a microcosmic analysis of early medieval socio-political organisation, the study of the lay elite in the development of Christian kingship holds significance in wider questions surrounding the relationship between religion and politics, the role of connection and disconnection in developing ideas of rulership, and the relationship between the secular and the sacred in early medieval northwestern Europe. Through highlighting the significant role of the lay elite in the development of sacred kingship, the decentralising of kings seen in recent literature (such as that by Damian Tyler) is supported in this blog. The lay elite were the cornerstone of a ruler’s support in the early Middle Ages, spreading ideas of sacred rulership through continental connections, and actively shaping the relationship between the secular and the non-secular through their positions of authority. Policing the relationships between the ruler and ruled, kingdom and continent, as well as the secular and sacred, the lay elite were perhaps more important than both ‘the Church’ and kings themselves in the development and spread of early medieval Christian rulership.

References

Primary Sources

Bede, The Venerable Saint. Bede’s Ecclesiastical History, edited by Bertram Colgrave and Roger Mynors (c.731AD; reprint, Oxford University Press, 2001).

William of Malmesbury. Gesta Regum Anglorum: The History of the English King. Edited by Roger Mynors, Rodney Thompson, and Michael Winterbottom. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press, 1998.

Secondary Sources

Markus, Robert. Christianity and the Secular. Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press, 2006.

Markus, Robert. ‘The Sacred and the Secular: From Augustine to Gregory the Great.’ The Journal of Theological Studies 36 (1985): 84–96.

Meier, Mischa, and Steffen Patzold. “Qualifying Mediterranean Connectivity: Byzantium and the Franks during the Seventh Century.” Early Medieval Europe 31 (2023): 380–404.

O’Brien, Conor. ‘The Origins of Royal Anointing.’ Studies in Church History 59 (2023): 27–47.

Story, Joanna. ‘Exiles and the Emperor.’ In Carolingian Connections: Anglo-Saxon England and Carolingian Francia, C. 750–870, 135–67. Routledge: London, 2003.

Tyler, Damian. ‘Reluctant Kings and Christian Conversion in Seventh-Century England.’ History 92 (2007): 143–282.

Van Nuffelen, Peter. ‘A Relationship of Justice: Becoming the People in Late Antiquity.’ In Civic Identity and Civic Participation in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages Editor, edited by Cédric Brélaz and Els Rose, 249–70. Brepols, 2021.

Walker, Jenny. ‘In the Hall.’ In Signals of Belief: Anglo-Saxon Paganism Revisited, edited by Martin Carver, Alex Sanmark, and Sarah Semple, 83–102. Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2010.

Werner, Joachim. The Sutton Hoo Ship Burial. Research and Publication between 1939 and 1980 (Oxford, 1985).

Further Reading

Mayr-Harting, Henry. The Coming of Christianity to Anglo-Saxon England. 3rd edition. London: Batsford, 1991.

Stancliffe, Clare. ‘Kings Who Opted Out.’ In Ideal and Reality in Frankish and Anglo-Saxon Society: Essays Presented to J. M. Wallace-Hadrill, edited by Patrick Wormald, 154–76. Oxford: Blackwell, 1983.

Thacker, Alan. ‘Bede’s Ideal of Reform.’ In Ideal and Reality in Frankish and Anglo-Saxon Society: Essays Presented to J. M. Wallace-Hadrill, edited by Patrick Wormald, 130–53. Oxford: Blackwell, 1983.

Wormald, Patrick. ‘Bede, Beowulf and the Conversion of the Anglo-Saxon Aristocracy.’ In The Times of Bede: Studies in Early English Christian Society and Its Historian, ed. Patrick Wormald and Stephen Baxter, 30–105. Oxford: Blackwell, 2006.

[1] Damian Tyler, ‘Reluctant Kings and Christian Conversion in Seventh-Century England,’ History 92 (2007): 143–282.

[2] The Venerable Saint Bede, Bede’s Ecclesiastical History, edited by Bertram Colgrave and Roger Mynors (c.731AD; reprint, Oxford University Press, 2001), book ii, chapter IX.

[3] Joachim Werner, The Sutton Hoo Ship Burial. Research and Publication between 1939 and 1980 (Oxford, 1985), pp.2-4.

[4] The Venerable Saint Bede, Bede’s Ecclesiastical History, edited by Bertram Colgrave and Roger Mynors (c.731AD; reprint, Oxford University Press, 2001), book ii, chapter IX.

[5] William of Malmesbury, Gesta Regum Anglorum: The History of the English King, ed. R.A.B Mynors, R. M. Thompson, and M. Winterbottom, vol. 1 (Oxford University Press, 1998), p.152-3.

[6] Joanna Story, ‘Exiles and the Emperor,’ in Carolingian Connections: Anglo-Saxon England and Carolingian Francia, C. 750–870(Routledge: London, 2003), p.158.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Conor O’Brien, ‘The Origins of Royal Anointing,’ Studies in Church History 59 (2023): 27–47.

[9] Mischa Meier and Steffen Patzold, ‘Qualifying Mediterranean Connectivity: Byzantium and the Franks during the Seventh Century,’ Early Medieval Europe 31 (2023): 380–404.

[10] Robert Markus, ‘The Sacred and the Secular: From Augustine to Gregory the Great,’ The Journal of Theological Studies 36 (1985): 84–96.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Jenny Walker, ‘In the Hall,’ in Signals of Belief: Anglo-Saxon Paganism Revisited, ed. Martin Carver, Alex Sanmark, and Sarah Semple (Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2010), p.96.