The Allestree Library, Bishop Martyrdom and The Pursuit of Episcopal Power

Chloe is a recent graduate in BA History with Study Abroad from The University of Exeter. She grew up on a council estate in a small village in Wales and was the first in her family to go to university. While at university, she stood as Vice President of Exeter Feminist Society and tutored low-income students with CoachBright, aiming to help eradicate educational disparity. When at university, Chloe was uncertain about the opportunities available to her for postgraduate study. UNIQ+ enlightened her on the process of applications and the life of a graduate student at Oxford, inspiring her desire for further study. She is passionate about the history of art, the history of the book, and gender theory.

How Richard Allestree and Henry Hammond Used the Texts of Bishop Martyrs to Justify the Existence of the Episcopacy

Let us set the scene: it is London, October 1646, and the ‘Ordinance for the Abolishing of Archbishops and Bishops’ has been passed after decades of anti-episcopal sentiment. This ordinance reified years of unofficial conduct towards individual bishops that saw many already excluded and impeached. At times, opponents of episcopacy referred to the persecuting bishops of the Marian regime as evidence that they were instruments of spiritual tyranny and, thus, required punishment.

We see this manifest in the publication of a pamphlet in 1641 from the ‘Smectymnuus’, calling for avengement for the Marian martyrs in the form of the abolition of bishops. This is the age of martyrs - old and new - as sites of symbolism and rhetoric. While the remembrance of the blood of the Marian martyrs was used to justify the incursion against bishopdom, many bishops themselves were eager to be martyred in a bid to legitimize their positions and their faith. Take Bishop Matthew Wren, for example, who refused to leave his imprisonment at the tower of London for nearly 20 years in the pursuit of Anglican martyrdom; however, officials were acutely aware of the danger of executing him for this reason. In such a tumultuous political and religious climate, martyrdom certainly proved itself as a significant emotive, mnemonic, and rhetoric device.

So, what is this to do with a small library housed in Christ Church College, Oxford? The Allestree Library sits atop a spiral staircase in the east-wing of the college, hidden behind a heavy door. It holds over 3,500 books, many annotated, ranging from theology to classics to politics. The library originally belonged to Richard Allestree, the Regius Divinity Scholar of Christ Church in the mid-17th century, who intended for the library to be used by proceeding Divinity Scholar’s.

Allestree was an ardent royalist and best described as Protestant, though his theology defies such strict categorisation. He belonged to a circle of scholars at Oxford that included notable names like royalist churchman Henry Hammond. In fact, many of Hammond’s books reside in the Allestree library. Hammond set up a fund to financially aid vulnerable bishops, so these insights into his reading activities proves extremely important for enlightening us on contemporary uses of bishop martyrdom.

The library – largely untouched in its 400 years - has been claimed a ‘time-capsule’ by the few scholars that have dedicated attention to it. It is in this vein that this library is so rare, being a pocket of history mostly unmodified. Around 20 of these books are focused on martyrdom, with 5 from early bishop martyrs. Interestingly, these books on bishop martyrs have much more marks of usage, indicating significance was afforded to them by their readers. This article examines two of the most heavily annotated books on bishop martyrdom, Epistoli Genuini Ignatii Martyris: qui Nunc Primum Lucem Vident ex Bibliotecha Florentina (1646) and S. Caecilii Cypriani Catheginensis Episcopi, Totius Africae Primatis, et Glorioissimi Martyris Opera (1617), that were used by Allestree and Hammond. The paratext of these books – annotations, folded pages, marks of usage – reveal rare insights into the intellectual pursuits of these key 17th century figures, specifically on how the evocation of martyrdom was used to afford legitimacy to the episcopacy.

Epistoli Genuini Ignatii Martyris: qui Nunc Primum Lucem Vident ex Bibliotecha Florentina (1646) is a publication of Ignatius of Antioch’s letters on his travels to his martyrdom in Rome in c. 108. Ignatius proved a basis of contention between Presbyterians and Episcopalians over the church order, especially in the wake of the death of Charles I. Jonathan Lookadoo argues that 17th century debates over the authenticity of Igantius’ texts aligned with wider discourses on ecclesiastical, episcopal, and ruling order. Ignatius, a bishop himself, reiterates the significance of the episcopacy throughout his epistles. In one instance, he writes: ‘your noble presbytery, worthy of God, is fitted to the bishop, as the strings to a harp.’. Likening bishopdom to the essential facet of an instrument, Ignatius tells his readers plainly that the bishop is a requirement to Christanity.

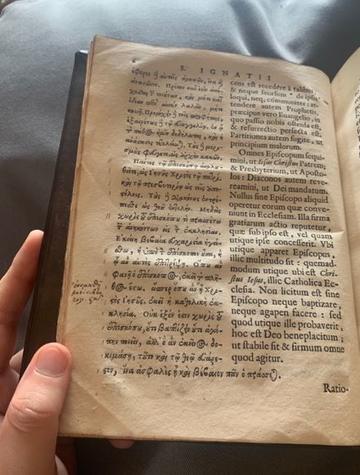

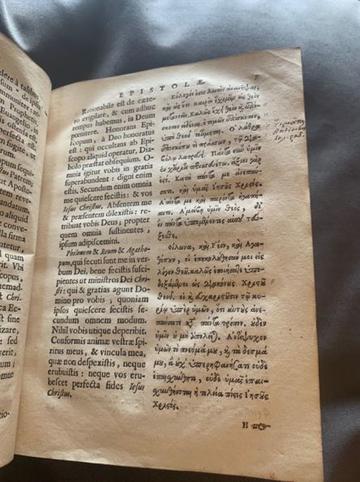

Those who supported the episcopacy, then, were more likely to defend the authenticity of Ignatius’ works and vice versa. This particular text in the Allestree Library was published in 1646 by Isaak Vossius, an influential royalist scholar known for his extensive library, relationships with key royal figures, and religious eccentricity. It is a bilingual parallel text in Greek and Latin, though the annotations are only in Greek. Interestingly, the front binding of the text is a pamphlet from September 1646 detailing the ‘affaires to the kingdome of England’, placing the timeframe of its use in-line with the passing of the ordinance for abolishing bishops.

The first 62 pages are littered with underscores, annotations, and tally marks, all in the same handwriting. This handwriting seems rushed, with some letters being illegible. Allestree seems to have approached this text with a sense of urgency, reflecting the significance of these texts in the intellectual pursuit of justifying bishopdom. It is also extremely interesting that he chose to confront the text in the Greek rather than the usual Latin. Allestree may have been wanting to engage with the language the text was originally written in to consider the original linguistic techniques of Ignatius more fruitfully. He might have been writing in Greek for security, as less people would be familiar with Greek over Latin. Allestree was operating at a time where the tide was turning against his religious ideals, so using a less-spoken language would have made him less vulnerable of being discovered in his pursuit for justifying the episcopacy. We cannot know for certain, however. What we do know is that Allestree was annotating and analysing Ignatius’ epistles in the context of religious dissonance.

Pages 6 to 7 seem to be counting the references to the honour or promise of ‘Antiochus’ (fig. 1 & 2). These brief references to Antiochus’ actions or disposition (Ignatius) continue on pages 9 and 14 where Allestree seems to refer to the submission of Antiochus. On page 41 there are two annotations referencing apathy and mercy or forgiveness alongside more tally marks (fig. 3). Pages 43 and 48 hold bigger chunks of annotations, though I admit I am not well-versed enough in Greek to translate them.

The rest of the text from the letters between Mary and Ignatius are unmarked and, presumably, unread. This is significant because it is these letters that were the locus of the legitimacy debate in the 17th century. Allestree not engaging with these epistles indicates an awareness of the dangers of going beyond authenticated texts to fuel his rhetorical and intellectual pursuits. It seems, overall, that Allestree seems to be tracking – and, indeed, counting – the rhetorical facets of the text. These concepts – honour, mercy, forgiveness – are central to Christianity and, thus, references to someone embodying these characteristics can be used rhetorically to justify their religious legitimacy. Allestree, then, seems concerned with intellectually proving the religious authenticity of Ignatius. Allestree was certainly a supporter of the episcopacy, becoming a bishop later in life, so it makes sense that he would afford so much attention to justifying Ignatius’ religious honour.

This pursuit for legitimizing Ignatius’ character and the epistles was also a pursuit for legitimizing episcopal importance. These annotations give us a crucial insight into the ways this intellectual legitimization was carried out.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Printed and published in 1617 by Anton Hierat, S. Caecilii Cypriani Catheginensis Episcopi, Totius Africae Primatis, et Glorioissimi Martyris Opera are the works of the martyred bishop Saint Cyprian of Carthage. Cyprian was born in North Africa in the early 3rd century and converted to Christianity in 249, soon after becoming the Bishop of Carthage amongst much contestation. Before his martyrdom under Emperor Valerian, Cyprian wrote various theological works such as Ad Donatum and De Ecclesiae Catholicae Unitate.

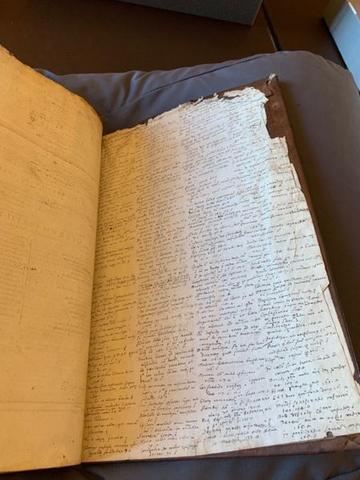

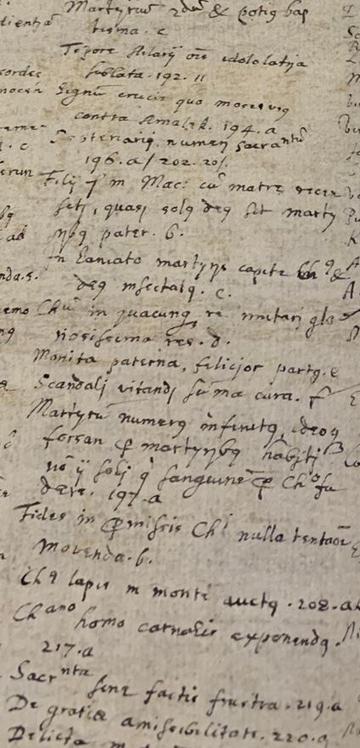

The text found in the Allestree Library was owned by Henry Hammond, reflecting his particular mode of note taking. Hammond certainly paid thorough attention to Cyprian’s text, dedicating three pages at the end of the text to fill with notes about the writings. There is a referencing system operating here, with Hammond making specific reference to pages when writing his thoughts up. Hammond was meticulous with his considerations of Cyprian’s journey, making multiple references to his act of martyrdom and his veneration of a martyr.In one note, he conveys his awareness of the centrality and continuity of martyrdom: ‘the martyr is infinite’ (fig. 4 & 5). The martyr, to Hammond, Allestree, and many more, is a transcendent symbol of religious dedication and sacrifice – a symbol that can be used to legitimise religious ideals.

Figure 4

Figure 5

While this text was undeniably used by Hammond, Allestree seems to have also read it. The same tally marks in the same pencil marks that were found in the epistles of Ignatius are littered over a few pages in Cyprian’s works, too. Cyprian’s martyrdom, like Ignatius’, was mined for rhetoric inspiration. The martyr as an infinite symbol was highly significant in the 17th centuries tumultuous religious climate, and Hammond and Allestree were aware. That they seemed to share this text reveals much about the uses of the book amongst like-minded scholars in the pursuit of intellectual justifications of their ideologies. In this case, Allestree and Hammond seem to have both consulted Cyprian’s texts with especial focus on his martyrdom as a bishop in the pursuit of legitimizing episcopal power. The book, clearly, was a powerful device to them. The fact that they afforded such meticulous and detailed attention to these texts shows both the centrality of the book and the martyr as tools of rhetoric.

The books in the Allestree Library provide unique perspectives and insights to history that have previously been mostly undiscovered. In this case, they have revealed Hammond and Allestree’s use of the book and the symbol of the martyred bishop as rhetorical tools in a period of religious turmoil. These texts were carefully and critically read by Allestree and Hammond, exhibiting their process of reading, and considering the rhetorical value of bishop martyrdom.

More substantial attention must be paid to unveiling Allestree and Hammonds specific responses to these texts, and how they fit more broadly into the religious and political contexts of the 17th century. Moreover, the Allestree Library as a whole must be mined for the remarkable and unique historical insights it’s books can reveal. Many of the texts have been owned by other influential figures such as William Cecil Baron, best known as Elizabeth I’s chief advisor who was instrumental in the beheading of Mary I. More than the texts themselves, the annotations and marks of usage reveal significant how these key figures responded to historical events, their intimate ideological beliefs and thoughts that may not have been public, and much more.

The Allestree Library is a central pocket of history that must be uncovered.

Further Reading:

Ralph Hanna and David Rundle, A Descriptive Catalogue of the Western Manuscripts, to c. 1600, in Christ Church, Oxford (Oxford, 2017).

Mark Purcell, ‘” Useful Weapons for the Defence of That Cause’” Richard Allestree, John Fell and the Foundation of the Allestree Library’, The Library, 6th Series, vol. 21 (1999), pp. 124-147.

Allen Brent, Ignatius of Antioch: A Martyr Bishop and the Origin of Episcopacy, (Continuum International Publishing Group, 2007).

Jonathan Lookadoo, ‘Expanding the Narrative: The Reception of Ignatius of Antioch in Britain, ca. 1200–1700’, Church History, vol. 89 (2020), pp. 1 – 23.

Susannah Brietz Monta, Martyrdom and Literature in Early Modern England, (Cambridge University Press, 2005).

Peter King, ‘The Episcopate During the Civil Wars, 1642 – 1649’, The English Historical Review, vol. 83 (1968), pp. 523 – 537.

Martin Lyons, Books: A Living History, (Thames & Hudson Ltd., 2020).