“One gold child’s bracelet”: Traces of Children in Stolen Property Documents from the Holocaust in Hungary

Barnabas Balint is a doctoral candidate at the University of Oxford under the supervision of Dr Zoe Waxman. His multi-lingual research (in English, French, and Hungarian) combines the history of childhood, gender, and identity, to explore Jewish responses to persecution. Currently, his PhD project focuses on developing age as an intersectional category of analysis for Jewish youth in Hungary during the Holocaust.

In July 1944, gendarmes in the city of Debrecen in eastern Hungary systematically searched for and confiscated belongings from the local Jewish population. As they did this, they recorded the valuables they took from each family, creating reams of documentary evidence relating to the Holocaust in Hungary. These documents survive today in the Hungarian Jewish Museum and Archives in Budapest. Over 50 carefully typed sheets stand as a testament to the expropriation of Jewish property, listing the belongings that were taken, including money, jewellery, and other valuable household items. These are not the kind of documents that easily tell a history of childhood, yet they contain clues and hints that are worth considering. Traces of children in archival documents like these remind us that young people suffered persecution too and provide a window into the experiences of the Holocaust’s youngest victims.

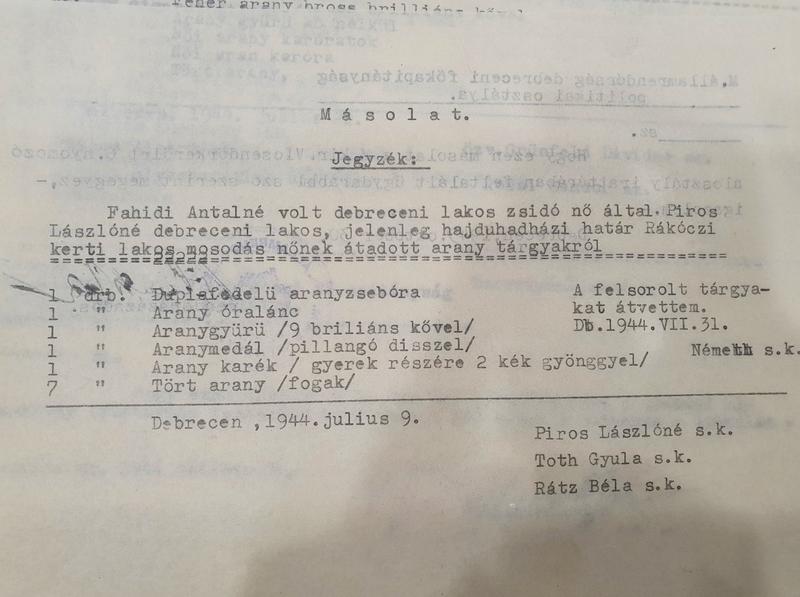

In one of the documents, dated 9th July 1944, we learn that one family handed over their valuables to a local laundrywoman. The report describes these valuables: 1 gold pocket watch, 1 gold watch chain, 1 gold ring with 9 stones, 1 gold medal with butterfly decorations, 1 gold child’s bracelet with 2 blue pearls, and 7 broken gold teeth.

Debrecen Gendarmerie Investigative Files, Hungarian Jewish Museum and Archives, XX-B, File 14 – Debreceni csendőrkerület

With its reference to a child’s bracelet, the document suggests that there was at least one child in the family. This provides a trace of a child in the archive – we may have no name or date of birth, but we do have a material possession that belonged to a child. Out of over 50 of these gendarmerie reports from 1944, only five of them have such references. One refers to a boy’s gold chain, another to a child’s seal ring, and another to a six-piece set of children’s ornamental forks and knives. One even details a girl’s trousseau – the clothes, linen and belongings her father collected in expectation of his daughter’s marriage. These are powerful images of children’s lives. Through them we see not only the existence of children in this history, but also the interruption of their lives and the futures their parents hoped for them. From the cutlery for the tea party that would never happen again, to the preparations for the daughter’s wedding that would never take place, these objects are a testament to the young lives that were destroyed by the Holocaust.

In documents that tell a history of the material dispossession of Hungarian Jews at the hands of the gendarmes and rank-and-file Hungarians, the inclusion of children’s belongings reminds us that children, as well as adults, suffered from antisemitic persecution. Yet we need to be aware of the limited picture of this persecution that these objects present. When the gendarmes carried out their official searches, they looked for high-value items: objects of gold, silver, and other precious belongings. Finding a record of children’s valuable objects in the documents, we see only a certain class of Jewish family and gain a perspective which hardly represents the majority of Jewish families and their everyday life experiences. By contrast, the testimonies of survivors often tell of how gendarmes stole children’s belongings, such as bicycles, taking these home for their own children. This kind of unofficial looting never made it into official documents but impacted a far greater proportion of Jewish children.

This disparity between the official image of the documents and the more intimate experience of survivors also prompts us to consider how the documents were created and the impact this process had on the families. The gendarmerie notes are short and to the point, describing the existence and transfer of the valuables. They are official, recording the signatures of those involved and the date of the report. They do not, however, explain why or how this took place. We know from the testimonies of survivors that during searches Jews were threatened with violence and strip searched in invasive, dehumanizing, and humiliating procedures, in what one Hungarian historian aptly described one of the ‘all time moral low points in Hungarian history’. While the Debrecen documents do not tell us how the searches were carried out, they do reveal the involvement of local gendarmerie in the expropriation of Jewish property. For the Jewish families that were subjected to this, the rank-and-file and state-sponsored theft of Jewish property reinforced the fundamental shift in their place in Hungarian society.

As the very system in which Jewish children had grown up in turned against them, their neighbours, the police, and the local government – figures that children are normally told to trust and go to for help – became their jailers. We see this new system in place through the gendarmerie documents. At their time of making, Jewish families in Debrecen were incarcerated in the ghetto, shortly before they were deported into the Nazi concentration camp system. There, approximately 4,028 Jews – nearly half the pre-1944 total – were murdered. The documents from Debrecen do not tell us about their deportation and murder, but they do tell us about the persecution they experienced in the months beforehand. This reveals the active role of Hungarian perpetrators in a history that often focuses on the actions of German occupiers.

When such documents remind us about the presence of child victims within this system, we are given both a sharp reminder of the totality of the Holocaust and an insight into how children’s lives changed as a result of persecution. Documents like the investigative notes from Debrecen do not tell this story fully, but they do reveal details of its existence, encouraging us to delve deeper into the lives of children otherwise represented merely by a belonging.