“Greeting to my little brother I would like to see him again” Examining the experiences of children and youth growing up in care in early 20th century Denmark

Amalie Olga Lyngsted is a PhD candidate at the SAXO-institute at the University of Copenhagen and the Danish National Archives. She is working on a PhD project examining the experience of children placed in care in early 20th century Denmark. Her fields of interest include the history of care and care institutions, the history of children and childhood, and the history of emotions in the 19th and 20th centuries. Her research is funded by the Danish independent research fund, who also funded her visit to University of Oxford and the Centre for the History of Childhood in Trinity term 2024.

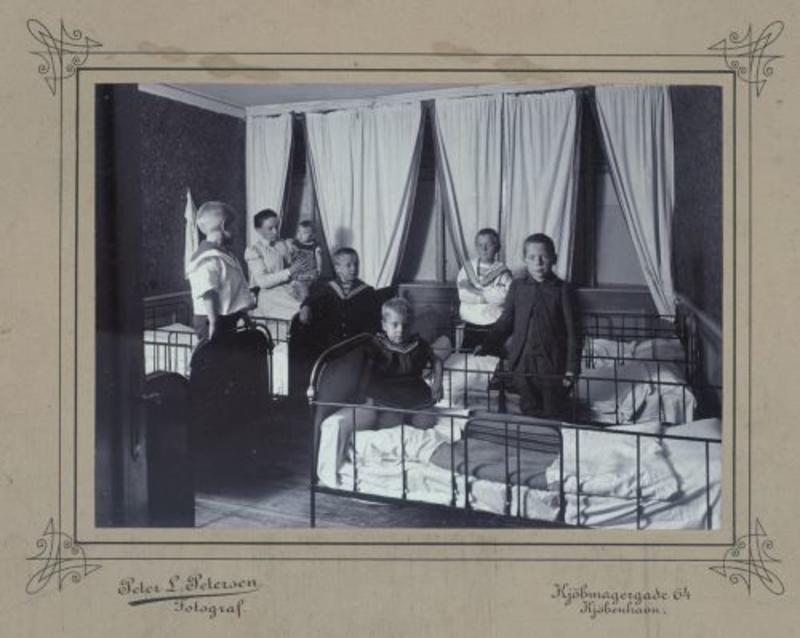

A bedroom for boys at the admissions home of the Organisation of N. Bang in Copenhagen, undated approximately 1900. Peter L. Petersen, Archive of the Organisation of N. Bang, The Danish National Archives.

In 1905, 43 children were admitted to the admissions department of the Danish philanthropic organisation, the Organisation of N. Bang. The children had been removed from the Copenhagen slums, placed in the organisation’s admissions home, and were subsequently observed to determine the best course for their future upbringing. Twenty of these children were placed into one of the organisation’s five children’s homes or with foster families in the Danish countryside. Fourteen were only admitted temporarily and were returned to their families after a short stay at the home. Two were unaccounted for in the annual statistics and seven were still living at the admissions home awaiting assessment by the end of the year.[1]

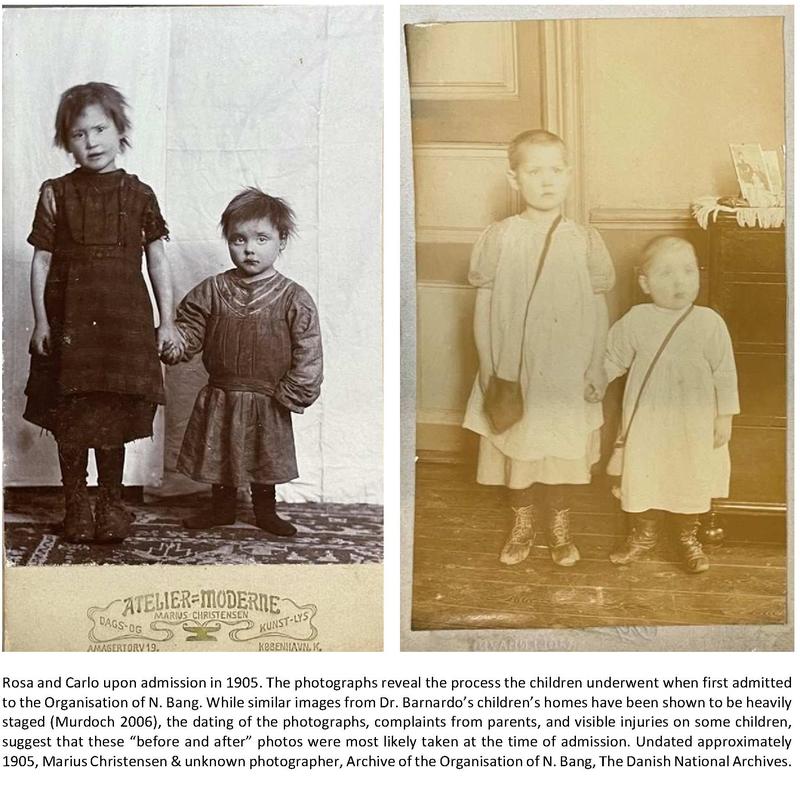

The Organisation of N. Bang operated in Copenhagen, Denmark, between 1897 and 1922, and was one of many private initiatives established in Denmark during the 1890s for the salvation of vulnerable children, as a part of what was named the Children’s Cause.[2] As part of the work on my Ph.D. dissertation, I spent the Trinity term of 2024 examining 78 case files from children and young people placed in care by the Organisation of N. Bang in the first decades of the 20th century. The aim was to examine the relationship between foster children and foster parents and through that historicise the concept of care. Two of these case files belonged to the siblings Rosa, aged five, and Carlo, aged three, most likely two of the seven children that were still at the Organisation of N. Bang’s admissions home in February 1906 when the previously mentioned annual report was published.[3]

The two children had been handed over to the organisation by their parents in 1905, and like most of the other children admitted to the Organisation of N. Bang they came from a “wretched home” marked by poverty.[4] In the spring of 1906, the two siblings were initially sent back to their parents. However, it did not take long before they were both admitted again, and by the spring of 1907, they were both placed in care, though not together: Carlo in one of the organisation’s children’s homes and Rosa with a foster family in the countryside.[5]

While Carlo almost disappears out of the organisation’s archive until eight years later, the same was not the case for Rosa, and her story began to unfold through my analysis. Sometime after Christmas in 1908, when Rosa was eight years old, she wrote a letter to the organisation’s secretary Miss Simonsen. The letter reflects the writing and literacy of an eight-year-old child. Mistakes in spelling and grammar are difficult to translate in a meaningful way. Yet, the mistakes such as those in Rosa’s greetings, and the lack of commas and full-stops are part of the way she tried to put her experiences of her first year in foster care into words, and they are therefore kept in the English translation of the letter cited below:

Dear Miss Simo

I would like to write to you and thank you for your kindness towards me Thank you so much for what you sent me for my birthday and for the Christmas present I was so happy about it. I am so happy here at home I go to school every day there are twenty-nine children in the school and we have a kind teacher whom we are very fond of but he will soon leave, and we are sad about that we will get a new teacher now I can read and do arithmetic and I will work hard to get better.

I would like to know if my brother is still at the children’s home or if he has found a home I long for my brother I often dream that we are playing together and sometimes walking to school together but when I wake up I don’t see him anymore now I don’t have much more to write I want to be a good girl but I don’t always remember to be one so I pray to my Saviour to help me always remember to be a good girl.

Many greeting to you dear Simo and thank you for being so good to me Greeting to my little brother I would like to see him again greeting to miss Hjensen and miss Jørsen and greet Mr Bang

Rosa Vitorie Tomsen

Greeting from Dad and Mom Marie and John

From her informal use of the titles “mom” and “dad” about the foster parents who only a year before had become Rosa’s primary caregivers to the reflections on her school and her wish to do better and be a good girl, Rosa’s letter opens up the questions about how these reflections came about. What was her relationship with her home and her new caregivers and how did she perceive and experience the care she received?

Spending a term at the Centre for the History of Childhood gave not only a space to be absorbed in my work with the sources but also a space for dialogue and shared reflection on the examination of children’s experiences in the past. Asking questions about how I listen to the voices preserved in the archive, and how I can understand the complexity of the experiences of children and young people in the past.

Rosa’s letter is but one reflection and one example of a child’s communication written at one specific moment in time in the context of being a foster child in Denmark, and not all letters looked like the one Rosa wrote when she was eight years old. As a child Rosa wrote that she was well, that her teacher was kind, she wrote that it made her sad that he was leaving and that she herself longed for her brother, and hoped that she could remember to be a good girl. All of these words communicate emotions and are connected to care: emotional care, practical care, caring for and about someone, and someone caring for and about her.

As Stephanie Olsen and Josephine Hoegaerts argue, emotions shape experience and the emotional language communicated by letters, such as the one written by Rosa in 1908, became my way into care both as an imagined phenomenon and as a practice. [6] Letters like those written by Rosa offer glimpses into how children themselves interpreted and communicated the care they received, their relationships with foster parents, and their experiences of being foster children.[7]

In both of the photos taken of Rosa and Carlo at time of admission, they were holding hands. A few years later, they were separated. The image of the two points to the direction of the project as a whole. A project about the experience of children growing up in care whose relationships were shaped and reshaped throughout their upbringing, by the organisation, by foster parents, the parents that had to give them up, and the children themselves.

[1] Annual report 1905 (Årsberetning), the archive of The Company of N. Bang in Copenhagen, The Danish National Archives.

[2] Some of these organisations are listed in: Jørgen Henrik Petersen, Klaus Petersen & Niels Finn Christiansen (red.) (2011) Mellem skøn og ret, Dansk velfærdshistorie bd. 2, 1898-1933.

[3] Based on Danish Archive Law and the EU GDPR Data Laws, the age of the material analysed in my dissertation makes it legal to show the sources in a non-anonymised form. However, ethical reflections have also been part of my decision to name children like Rosa and Carlo in my research. In making my decision, one of my main concerns was care-leavers’ experiences of the harmful practice of being reduced to a number in many institutions. This was shown in the large examination of Danish institutional history: Jesper Vaczy Kragh, Stine Grønbæk Jensen & Jacob Knage Rasmussen, På kanten af velfærdsstaten (2013). My hope is that, through careful and contextualised analytical work, I will be able to present the children in my research, in a respectful way, as individuals who lived and experienced a time in history.

[4] Records, Rosa Victoria Thomsen & Carlo Thomsen, no. 1888 og 1889. Archive of the Organisation of N. Bang, The Danish National Archives.

[5] Records and individual case files, Rosa Victoria Thomsen and Carlo Thomsen, no. 1888 og 1889. Archive of the Organisation of N. Bang, The Danish National Archives.

[6] Josephine Hoegaerts and Stephanie Olsen, ‘The History of Experience: Afterword’, in V. Kivimäki et al. (eds.), Lived Nation as the History of Experiences and Emotions in Finland, 1800–2000 (2021) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-69882-9_15

[7] Drawing from the concept of Emotional Echoes, Karen Vallgårda & Katrine R. Larsen (2021) https://curis.ku.dk/ws/portalfiles/portal/260504656/Emotional_Echoes.pdf