Generations and cohorts, adults and children

Dr Laura Carter is an historian of modern Britain whose work focuses on histories of education, gender, and social change. Her first book, Histories of Everyday Life: The Making of Popular Social History in Britain, 1918-1979 (OUP, 2021) was nominated for the Royal Historical Society Whitfield Book Prize, 2022 and will be published as a paperback in February 2024. Since 2017, she has been part of a team of historians working on the ESRC-funded project ‘Secondary education and social change in the United Kingdom since 1945’. Her most recent article arising from this project is about women who attended secondary modern schools in Britain between the 1940s and 1960s and how they navigated school to labour market transitions, it is available to read open access here. She is a Lecturer in British History at Université Paris Cité in Paris, France and a member of the CNRS-funded research unit LARCA - UMR 8225.

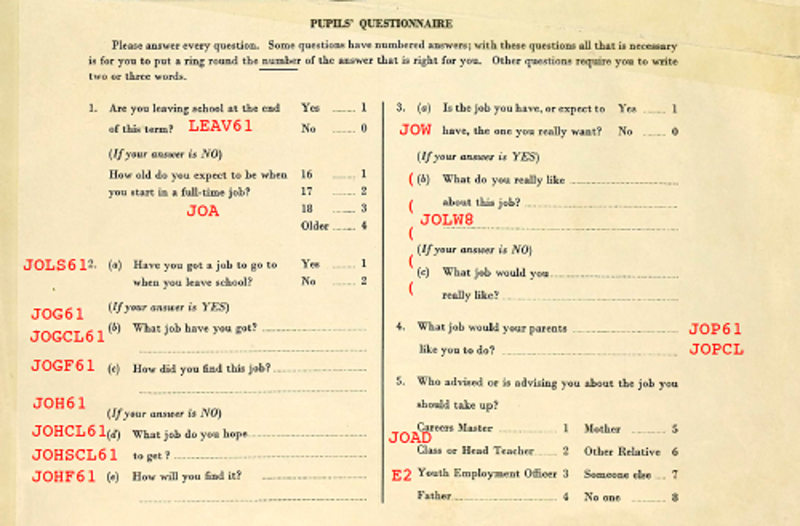

I spent my research leave during Michaelmas Term 2023 in Oxford, hosted as a POP (Paris-Oxford Partnership) Fellow by TORCH, the Centre for the History of Childhood, and St Catherine’s College. This precious time allowed me to make progress on a longstanding project, funded by the ESRC and shared with colleagues at the University of Cambridge, Peter Mandler and Chris Jeppesen, called ‘Secondary education and social change in the United Kingdom since 1945’. Specifically, I was writing up parts of our forthcoming book, which uses, among other sources, qualitative data from the National Survey of Health and Development (NSHD), or 1946 birth cohort. The NSHD has followed 5362 people born in March 1946 throughout their lives, regularly collecting health and social data, including educational data.

I want to use this blog post not to talk about the fine details of that research (you can read more about it and our findings in recent open access journal articles we have published)[1], but to reflect on some questions about how we frame shared experiences of education, in relation to change over time.

During my time in Oxford, I found myself pondering over the different but overlapping languages of ‘generations’ and ‘cohorts’. Social and medical scientists tell us that cohorts are more precise groupings, especially for the purpose of longitudinal research. Our colleague J. D. Carpentieri raised this at an event I ran at TORCH in October, ‘Social-historical approaches to British birth cohort data’, pointing out that when life course researchers need to communicate their cohort-based research to the general public, generation is king.[2] The language of generations pervasively populates everyday life, in the media and on social networks, especially when it comes to educational experiences. Britain’s shift from a bipartite (grammar and secondary modern schools) to a comprehensive secondary education system over the course of the 1950s and 1960s is seen readily through this lens; we can talk about the ‘baby boomers’ at grammar school, or millennials at comprehensive schools, for example.

But look a bit closer and the fuzziness of generations becomes immediately clear. Britain’s four national birth cohort studies (1946, 1958, 1970, and 2000) helpfully complicate a school-by-generation matrix. For example, we can readily find members of the 1946 cohort attending comprehensive schools (280 study members in England and Wales) and members of the 2000 (aka millennium) cohort attending grammar schools (c.353 study members in England, c.571 in Northern Ireland).[3] But the 1958 cohort (the late ‘boomers’) are the real problem. They went to secondary school in the 1970s, turned sixteen in 1974, and 59% of the cohort attended a comprehensive school. The rest were in the old, bipartite system, and many of them experienced both systems over the course of their secondary careers, with schools in a state of transition.[4]

The language of generations is organic and pliable, easily fostering imagined communities around shared educational experiences, traumatic or triumphant. It is also a language that can be used to describe experience in a relational way, with respect to generations coming before or after. Generation talk is therefore useful for measuring out, often retrospectively, gain and loss, between groups of different ages. Cohorts can mess this up, with their precise data.

Yet, even with the cohort data at my fingertips, I find myself ever drawn to thinking through generations when it comes to secondary education and social change in the UK. This has been reinforced by the opportunity to talk more to experts in the history of childhood, especially when attending and speaking at the Centre for the History of Childhood’s lunchtime seminars in Oxford last year. Thinking through the category childhood, rather than about pupils as I usually do, bought into sharper focus the category of adulthood. Each generation’s educational experiences happen at school, but change is the product of adults constantly feeding back into the school system, as teachers, parents, activists, and researchers. Children respond, through assent or dissent, as well as driving change themselves through their own intra-generational cultures and activism.

For example, one of the big topics in our book is how far and in what ways ‘second wave’ feminism, one of the most important sources of social change in late-twentieth century Britain, touched secondary schools. Sources from the Women’s Liberation Movement, for example magazines and oral histories, give one slice of this picture. But we might think more broadly about the inheritance left by grammar and secondary modern school educated women, to girls of the next generation. Some of this female generation were activists, but in much larger numbers, the grammar-school women were schoolteachers in comprehensive schools and the secondary modern school leavers were mothers of those pupils. These two groups of adult women, combined with a rather unsung group of feminist sociologists, worked to hold the UK education system accountable to gender inequality over the course of the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. The girls at comprehensive schools then made space for themselves by staying on at school longer, taking more exams, and cautiously crossing gendered subject boundaries. Black and Asian schoolgirls were much less likely to have champions and/or representation in the generation before them in UK schools before the 2000s, and so they benefited less from the inter-generational lift.

Interactions between adults and children at school and at home are the driving force behind the relationship between secondary education and social change in the UK since 1945. As historians, we need cohorts to describe this complicated story, but we also need the language of generation to interpret it.

Image: Pupils’ Questionnaire at age 15 (1961) from the National Survey of Health and Development (NSHD), reproduced with the permission of the Medical Research Council Unit for Lifelong Health and Ageing at UCL

[1] Laura Carter J.D. Carpentieri, & Chris Jeppesen, 'Between life course research and social history: new approaches to qualitative data in the British birth cohort studies', International Journal of Social Research Methodology, (2023), pp. 1-28 [https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13645579.2023.2218234]; Laura Carter, 'The Hairdresser Blues: British Women and the Secondary Modern School, 1946–72', Twentieth Century British History, 34 (2023), pp. 726-53 [https://academic.oup.com/tcbh/article/34/4/726/7194712].

[2] As, for example, in this report: Bozena Wielgoszewska, JD Carpentieri, David Church, and Alissa Goodman, 'In their own words: give generations of Britons describe their experiences of the coronavirus pandemic', (2020)

[https://cls.ucl.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/In-their-own-words-Init....

[3] J. W. B. Douglas, J. M. Ross, and H. R. Simpson, All Our Future (1968), p. 58; John Jerrim and Sam Sims, ‘The association between attending a grammar school and children’s social-emotional outcomes: New evidence from the Millennium Cohort Study’, British Journal of Educational Studies (2020), 68:1, pp. 25-42.

[4] Ken Fogelman (ed.), Britain’s sixteen-year-olds (1976), p. 40.