Gender Dynamics and Feminist Intervention in Youth Clubs in Late Twentieth-Century England

Ryan Aslett has just finished his second year studying Geography at the University of Exeter, Cornwall. He will spend the following year studying at Radboud University in the Netherlands. He is interested in how modern-day austerity has impacted young people's spatialities, social spheres and holistic development. In his dissertation, Ryan is researching how gradual withdrawals of funding and policy neglect for youth services over the last decade have impacted the spatial realities of young people. He aims to build on his research into the statutory provision of informal education in the future. Outside of academia, he volunteers at a Squirrel Scout section in Redruth and works part-time as a bartender.

The evolution of youth clubs in late 20th-century England provides a microcosmic lens into broader societal shifts in gender dynamics, revealing grassroots feminist interventions and their pivotal role in reshaping perceptions, challenging longstanding inequalities, and influencing modern-day approaches to youth-focused programs.

The youth club movement's roots can be traced to the National Organization of Girls Clubs in 1911. However, mergers with boys’ associations led to the marginalisation of girls as the organisation became the National Association of Girls and Mixed Clubs from 1943 and the National Association of Youth Clubs (NAYC) from 1963 (Spence, 2010). The Fairbairn-Milson report (1969) recognised that "girls are relatively ill-provided for" (156), including through education, emotional support, and opportunities. Although the reasons for these discrepancies are not entirely clear, they are evident in multiple aspects of youth services. The report also noted that ‘many boys and girls need help establishing healthy relationships with members of the opposite sex’ (156). However, the report did not provide any recommendations for addressing these issues. It suggested training-related changes and influenced youth services naming conventions, but its tangible impacts were limited, as pointed out by Davies (1999; 133). The Department of Education and Science (DES) rejected the report in 1971, and this lack of direction hindered progress in youth services throughout the 1970s (Doug, 1997 in ibid; 200). Its ambiguous and sometimes contradictory recommendations reflected political compromises that often interfered with, rather than aided, the service's work with youth (Smith, 2003).

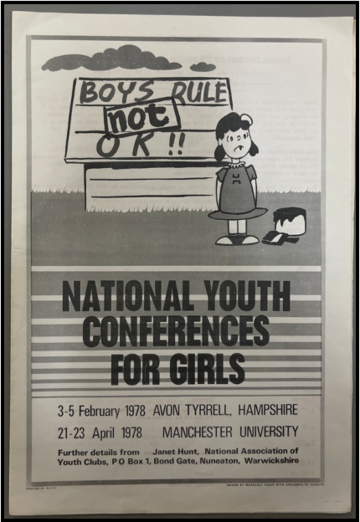

Figure 1: BOYS RULE NOT OKAY conference (NAYC, 1978)

As the youth club movement progressed into the late-twentieth century, girls and youth workers began to take matters into their own hands, fighting against this marginalisation. (1999; 133). In 1978, recognising systemic inequalities, the NAYC established the Girls' Work Unit and initiated the BOYS RULE NOT OK conferences (Figure 1). These events were aimed at girls and young women aged 15 to 21, providing a platform to discuss women's role in a changing society. Health, education, employment, violence, and family were explored.

These initiatives must be viewed in the context of the women's liberation movement, which was gaining momentum during this period (Bruley, 2016). The second wave of feminism advocated for equal rights, challenged societal norms, and pushed for women’s representation in various sectors.

The women's liberation movement aimed to reshape everyday perceptions and interactions, not just to gain rights at the legislative level. The NAYC events similarly aimed to break gender norms by offering activities like canoeing, self-defence, moped riding, and home repairs, traditionally seen as male-oriented (NAYC, 1978). These feminist-led initiatives in youth clubs were microcosmic examples of the societal change the women's liberation movement sought to instil. The aim was to ensure equal representation and challenge deeply rooted gender stereotypes by acting on the ground level in local communities to foster transformative change.

Sylvia Crocker's study, conducted at a Shropshire mixed-gender youth club, provides a revealing glimpse into the inequalities that girls faced in youth clubs. Her work, penned for her Shropshire Youth Worker’s Certificate, is archived at the University of Birmingham’s Cadbury Special Library, but without a date. Although the certificate's level is not specified on the cover sheet, the methodology and findings suggest that it follows the structure of the Level 3 Certificate. This qualification prepared individuals to lead work with young people in various youth work settings (ETS, 2015). Crocker had no experience at the youth club nor prior knowledge of its structure, facilities, or attendees. The preliminary findings show that in the unnamed youth club with a regular attendance of 30 young people and supervised by four leaders, facilities and organised games were used only by the boys. Crocker observed the areas and social environments within the youth club where young people chose to gather and the interactions, they had with the youth workers. Crocker’s first impression of the club was positive, described as having a ‘lively atmosphere, with a good relationship [between leaders and young people].’

Despite this lively exterior, deeper gender imbalances lurked, as evidenced by Crocker's pointed observations. Crocker asked the interesting question, ‘But where are the girls?’ The boys and the male youth workers answered, ‘If you want to see the girls, they’ll be in the toilets.’ Four of the ten girls attending the two-hour session were ‘briefly’ talking to the boys in the corner of the main hall. The others were not present in the main activities. For instance, boys situated themselves at snooker tables and dart boards. There was also a noticeable gender imbalance in leadership regarding overseeing games, with male youth workers being more involved and female youth workers being confined to the coffee bar. This trend was even more striking when Crocker received comments about the attendees from the youth workers. The leadership exhibited bias, with boys receiving praise, ‘the boys are easier to work with,’ and the girls being dismissed because ‘girls are interested in relationships, not games’. Even Crocker’s first impression of the girls painted them to be ‘noncommittal, suspicious and showed little real enthusiasm.’

Crocker fostered connections with the girls in subsequent visits, enhancing their confidence and challenging biases through craft activities, including toy and jewellery making. At first, the girls responded to the new activities with disarming comments such as ‘I can't do something like that’ and ‘I can't sew - my teacher says I'm hopeless.’ The girls' negative self-perceptions and doubts indicate societal expectations and biases, which align with feminism's goal of addressing gender-based inequalities and promoting equal opportunities. Crocker's dedication to positivity, support, and optimism encouraged collaboration and recognition of effort and provided a safe and supportive environment. After five sessions, Crocker observed a transformation in the girls' attitudes and behaviour. The girls' comments showed increased self-confidence, a sense of accomplishment, and a desire to share their successes with others. At the same time, the club's progress was notable.

The positive interactions between the girls, the leaders, and Crocker, as well as the sudden willingness of the leaders to support the girls with resources, underscores the potential of feminist principles to foster positive change within the group dynamics. The girls’ desire for future sessions and the leaders’ commitment to continuing the engagement further emphasise the success of Crocker’s approach in promoting a more inclusive, confident, and empowered atmosphere.

Although there was considerable progress in installing a sense of self-worth in the girls and enabling them to voice their interests, uncertainties remained. Crocker was apprehensive about whether youth services could change their biases, a broader question that the feminist youth work movement grappled with. This period showcased the innovative potential of youth work and revealed the inherent tensions and challenges of embedding feminist principles in its fabric. The publication date was not available within the document but was placed with the other material discussed in this blog. It is uncertain, but Crocker’s work may have influenced further research projects within the NAYC.

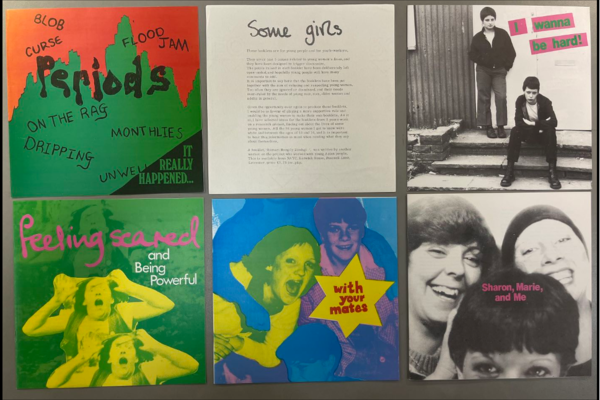

Figure 2: Some Girls Posters (NAYC, 1982)

Some Girls was an Action Research Project funded between 1978 and 1980 by the DES and the NAYC. The Equal Opportunities Commission and the Gulbenkian Foundation provided substantial support, underscoring the importance of respecting girls and encouraging conversations around gender biases. The study examined the personal lives of girls aged 13 to 16 and received mixed reactions from schoolteachers. Journalist Mark Jackson described the study as ‘too shocking,’ and it allegedly caused discomfort among school staff, prompting the DES to question the methods used by the youth workers.

Three workers, Leah Thorn, Laxmi Jamdagni, and Carola Adams, conducted the project, engaging over 160 girls. They captured the girls' words and activities with tape recorders and cameras. Initially, targeting ‘at risk’ girls, such as ‘young black and Asian, unmarried mothers, and school-excluded girls,’ the team realised these labels biased their perception. They then aimed to see the girls as whole individuals, not limited by stereotypes. Drawing from their diverse backgrounds, Thorn, and Adams, among others, employed innovative methods to gain a holistic understanding of these young women's lives (see Figure 2). Thorn, with her background in psychology and sex education, focused on validating young women's experiences, while a former craft teacher, Adams, connected with the girls through hands-on activities.

Parallel to this research-driven approach, artistic and creative ventures, such as the Madeley Women’s Writing and Designing Group (MWWDG), sought to engage young women with youth work. Formed in 1982 in Telford, the MWWDG, supervised by Adams, was an initiative for young women in the summer after leaving school. The group aimed to give them a platform to express their thoughts and ideas publicly. The content produced by these young women was not just creative expression; it was a tool for challenging societal norms and sparking essential dialogues. Initially, it was reported that the young women were reserved, viewing Adams as a teacher. However, they gained confidence, shared personal matters, and developed a strong bond.

The MWWDG was tasked with creating educational materials based on Adams and Thorn's Some Girls study findings. The materials included booklets, leaflets, and posters to spark conversations among young people and adults. The topics covered various issues, including challenging traditional femininity, sexual vulnerability, menstruation, and sexuality. These materials presented an assertive perspective. They were similar in tone to Spare Rib and Shocking Pink magazines (Gough-Yates, 2012).

Thorn then organised training sessions for youth workers centred around the materials. Some sessions, organised through various youth work agencies, were only for women, while others were mixed groups. The goal was to discuss youth workers' activities, their attitudes towards young women, and their experiences of sexism.

Men’s inclusion changed the dynamics, leading to valuable discussions about their roles in girls’ work. Thorn mentioned in the report that men’s reactions to the training sessions varied. Some men recognised the issues of sexism and oppression and were committed to addressing them. These men were interested in understanding young women's experiences and taking action within their youth organisations to combat sexism. As Delap (2017:224) highlights, ‘Men came to an awareness of feminism through the politicisation of their female partners and friends.’ However, there were also instances where men had no intention of listening or understanding. In mixed sessions, some men dominated conversations, even speaking over women. Thorn also suggested that including men in the sessions sometimes made women feel less safe to explore personal issues. This underlines the delicate balance needed when incorporating diverse groups into sensitive discussions, ensuring everyone feels secure and heard.

The history of late-twentieth-century youth clubs reveals not only sustained gendered stereotyping and inequalities, but also the impact of grassroots feminist advocacy. Crocker's detailed examination of a Shropshire youth club offers an enlightening glimpse into the experiences of girls during this era. At the same time, the Some Girls project and the Madeley Women's Writing and Designing Group stand as a testament to how local endeavours could redefine societal expectations and uplift side-lined voices. The archives created by these groups can start to reveal the intricate, multi-layered stories of girls and young women, and the communities they formed.

This history can be connected to contemporary studies, such as Brown and Donnelly's (2023) exploration of identity and space or Davies' (2018) analysis of austerity's impact on youth services, to reveal how youth clubs are deeply tied to broader socio-political changes. Kraftl's (2014) emphasis on alternative educational spaces underscores the adaptability and significance of youth clubs in modern-day contexts.

The modern emphasis should be on creating youth spaces that nurture expression, authenticity, and unconventional pursuits for everyone. As youth clubs are mirrors reflecting broader societal transformations, modern-day policymakers and educators must harness their inherent potential to sculpt programs that are dynamic, inclusive, and adept at confronting contemporary challenges. In valuing the historical lessons and the potential implications of such clubs, we carve pathways toward genuine equality, vibrant self-expression, and holistic empowerment.

Bibliography:

Primary Sources:

Arts Report (n.d.). From old wives’ tales to new outlooks [News Article]. Cadbury Special Archive. https://calmview.bham.ac.uk/GetDocument.ashx?db=Catalog&fname=MS227.pdf

Crocker. S (n.d.). Project on Group Work with Girls. Shropshire Youth Workers’ Certificate Course. Cadbury Special Archive. https://calmview.bham.ac.uk/GetDocument.ashx?db=Catalog&fname=MS227.pdf

Department of Education and Science (1969) Youth and Community Work in the 70s. Proposals by the Youth Service Development Council (The Fairbairn-Milson Report), London: HMSO. Extracts in the informal education archives, http://www.infed.org/archives/gov_uk/ycw70_intro.html

Jackson, M. (1982). Study too Shocking. [News Article]. Cadbury Special Archive. https://calmview.bham.ac.uk/GetDocument.ashx?db=Catalog&fname=MS227.pdf

National Association of Youth Clubs (1978). Work with Girls. Youth Clubs Magazine. https://solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/permalink/f/n28kah/oxfaleph012365232

National Association of Youth Clubs (1982). BOYS RULE NOT OK Conference [leaflet]. Cadbury Special Archive. https://calmview.bham.ac.uk/GetDocument.ashx?db=Catalog&fname=MS227.pdf

National Youth Bureau (1982). Fruitful Research [poster advert]. Some Girls. https://calmview.bham.ac.uk/GetDocument.ashx?db=Catalog&fname=MS227.pdf

Stein, S. (1982). Some Girls. [Letter]. Cadbury Special Archive. https://calmview.bham.ac.uk/GetDocument.ashx?db=Catalog&fname=MS227.pdf

Thorn, L (n.d.). ‘Some Girls Report: Equal Opportunities Commission and the Gulbenkian Foundation. https://calmview.bham.ac.uk/GetDocument.ashx?db=Catalog&fname=MS227.pdf

Thorn, L. & Adams, C. (1982). “Some Girls” A Series of British Posters. National Association of Youth Clubs. Cadbury Special Archive. https://calmview.bham.ac.uk/GetDocument.ashx?db=Catalog&fname=MS227.pdf

Secondary Sources:

Bruley, S., (2016). Women's Liberation at the Grass Roots: a view from some English towns, c. 1968–1990. Women's History Review, 25(5), pp.723-740.

Davies, B. (1999) “From Thatcherism to New Labour. A History of the Youth Service in England Volume 2: 1979-1999”, Leicester: Youth Work Press.

Delap, L., (2017). Uneasy Solidarity: The British men’s movement and feminism. The Women’s Liberation Movement: Impacts and Outcomes, pp.214-236.

Doug, N (1997). An Outline History of Youth and Community Work in the Union, 1834-1997. Pepar Publications.

ETS (2015). The Coherent Route of Recognised Youth Work Qualifications in Wales. https://etswales.org.uk/resource/coherent-route-bilingual-dec-2015_2.pdf

Gough-Yates, A., (2012). ‘A Shock to the System’: Feminist Interventions in Youth Subculture—The Adventures of Shocking Pink. Contemporary British History, 26(3), pp.375-403.

Spence, J., (2010). Collecting women’s lives: The challenge of feminism in UK youth work in the 1970s and 80s. Women’s History Review, 19(1), pp.159-176.

Smith, M., (2003). Youth and community work in the 70s. Infed. https://infed.org/mobi/youth-and-community-work-in-the-70s/

Further reading:

Brown, C. and Donnelly, M., (2023). A ‘Micro’-Spatial Lens on Identity and Education. In Space, Identity and Education: A Multi Scalar Framework (pp. 29-55). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Davies, B., (2018). Austerity, youth policy and the deconstruction of the youth service in England. Springer.

Fenwick, T., Edwards, R. and Sawchuk, P., (2015). Emerging approaches to educational research: Tracing the socio-material. Routledge.

Kraftl, P. (2014). What are alternative education spaces - and why do they matter? Geography, 99(3), 128–138. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4382539\7

Mills, S. and Waite, C., (2022). The state and voluntary sector in austere times: 10 years of National Citizen Service. Geography, 107(1), 38–45.