Ecclesiastical History Society Summer 2024 Conference: The Church and the Military

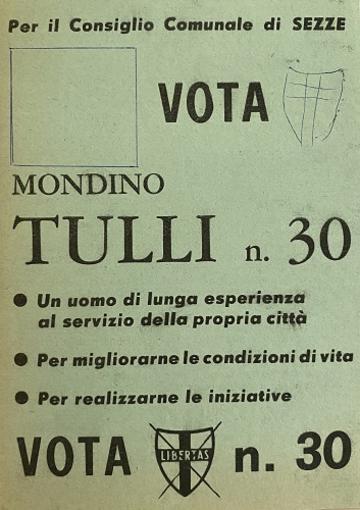

Raimondo Tuli Christian Democratic Electoral Ballot. From the Raimondo Tulli Papers in Rome, Italy

Born and raised in Italy but having completed her undergraduate studies at Georgetown University, Angelica Rossi-Hawkins is now a second-year PhD student at the University of Oxford. Her research primarily concerns studies of masculinity and elite culture in post-WWII Italy. By examining a number of clusters of upper-middle class, male networks of solidarity from 1945 to the mid-1970s, she hopes to understand the fabric of the postwar democratic ‘classe dirigente’. While working on her thesis, she also continues to research the development of Christian Democratic politics in the 20th century, and remains broadly interested in the history of gender, the history of friendship, and – when time allows – 19th and 20th century art history. She invites anyone to reach out on LinkedIn!

Ecclesiastical History Society Summer 2024 Conference: The Church and the Military

The EHS’s Summer 2024 conference gathered for three days in July at the University of Durham. The conference, which examined the relationship between church and military institutions, included papers that spanned geographically, chronologically, and thematically, to feature varied approaches and interpretations of this important pairing.

The period of Nazi occupation in Rome – from September 1943 to June 1944 – has long captured Europe’s imagination as a testament to the myriad pains, contradictions, and heroics of the Second World War. Still, despite the volume and variety of study devoted to this dramatic period, from films like Roberto Rossellini’s Rome Open City to seminal studies like David Kertzer’s The Pope and Mussolini, this brief but rich period remains shrouded in mystery, and evidence of collaboration and resistance alike has receded deeper into private archives and personal memories.

But one such private archive has been salvaged and sheds new light on this important time as a fulcrum of crucial patterns of transition from Fascism to postwar democracy. Raimondo Tulli, a bureaucrat born near Rome in 1904 and active within both the Fascist colonial administration as well as the postwar Christian Democratic state, left a trove of documents ranging from personal diaries to private letters to photographs documenting the life of an upper-middle class Roman in the mid-twentieth century.

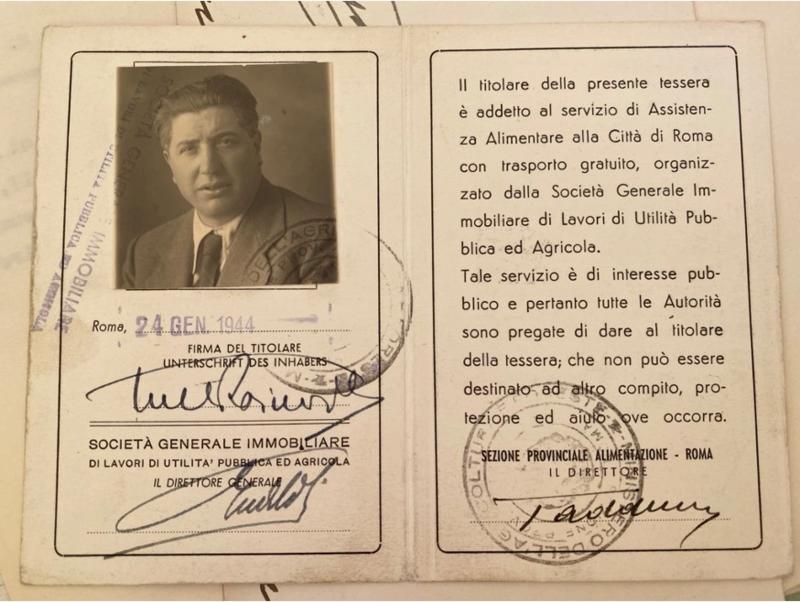

Company identification granted to Raimondo Tulli in January of 1944 by the Società Generale Immobiliare, certifying his participation in the company’s occupation-era provisioning efforts. Drawn from the Raimondo Tulli private archive in Rome, Italy

Tulli’s letters from 1943-1944 are riveting, fit for a neorealist classic: accounts about his Jewish wife, close friendships with the Pope’s closest confidants and advisors, and accounts of narrowly-escaped partisan and Nazi attacks on civilians animate this rich formerly-untouched archive. Perhaps most salient, however, is evidence of previously undiscovered mechanisms of collaboration between the Vatican, as represented by a Holy See-owned contracting company called the Società Generale Immobiliare (Sogene), and emerging resistant cells in northern Lazio and Tuscany. Through informal networks of solidarity, pooling influence and strategically calling in favours, Tulli smuggled weapons and people in and out of occupied Rome under the guise of managing a Vatican provisioning operation. Tulli did not operate alone: an entire class of former military officials who had met while in the colonies–all of loose Fascist fervour but professing patriotic sentiment–came to Tulli’s succour. Of this group, officials still enlisted in the military by the summer of 1943, such as Col. Teseo Madonna, provided military vehicles and infrastructure for the project, while Angelo Savini-Nicci, a future Croce Rossa Italiana president, used his important, if declining, aristocratic family origins to open doors to the Vatican for the rest of Tulli’s more nouveau-riche middle class colonial circle.

While the contribution of these efforts to the ultimate collapse of Nazi occupation and allied victory are difficult to gauge, their effect on the postwar careers of this cluster of ex-colonial men is undeniable: all the men mentioned in Tulli’s accounts relied on Vatican testimonies to soften their postwar purge-trial sentences and went on to serve in the uppermost chambers of Italy’s postwar political hegemon, the Christian Democratic Party (DC).

This never-before told story of Vatican and military collaboration during Nazi occupation, then, is more than an anecdotal demonstration of collusion and self-salvaging, or of ‘playing all sides’ by the Catholic church in a moment of political transition; it is uniquely exemplary of emerging patterns of Italian postwar politics. The end of the Second World War, and specifically the power vacuum it engendered in Rome, facilitated the development of a mutually-beneficial and long-lasting solidarity between the more technocratic arm of the Italian ex-colonial military and the Vatican. This collaboration, enacted through unofficial channels of male solidarity, is demonstrative of a new, binding, and mutually-modernising contract between church and ex-military administrators that would continue to act both on collective memory of the war as well as on the politics of the emerging nation. The church and the military, in a moment of crisis for both, found a consequential space in Italian postwar democracy by constructing a shared, super-partes apolitical approach to patriotism.

The collaboration acted as a salve for personal consciousness and identity-formation while state, family, and civil society structures unravelled and reformed in the final years of the war. This cooperation between Sogene and Tulli’s military cohort would go on to shape the self-understanding and identities of these DC administrators throughout the ends of their careers in the 1970s and 1980s. Fascist military colonial administrators, in collaborating with Sogene, became Catholic patriots, whose devotion to the patria transcended political affiliations. Nazi occupation, for Tulli’s cohort, thus provided a crossroads of consciousness, an opportunity to reinvent and rehabilitate the meaning of their participation in the Fascist efforts in Ethiopia and Libya, while the Vatican situated itself at the heart of a nascent, emerging, self-aware class of upper-middle class male administrators.

Tulli’s papers open new chapters into the exploration of the period of Nazi occupation in Rome. Novel evidence of Vatican and military cooperation comes to life through the story of Tulli and his male military companions, tracing the emergence of an era-defining political and social solidarity that would reinforce the DC and define postwar European politics for decades.