Childhood transitions in Edo period Japan

Dr Pia Maria Jolliffe FRHistS is a Fellow at Blackfriars Hall, University of Oxford. She teaches early modern and transnational Japanese history. Her current book project focuses on children, emotions and the politics of memory in 16th and 17th century Japan. Pia is a steering committee member of the Centre for the History of Childhood and a member of the Japanese History Workshop.

In this blog, I would like to share with historians of childhood some remarkable features of childhood and youth transitions in premodern Japan. In particular, we shall look at the so-called Edo period which lasted from 1603 until 1868 when Edo (today’s Tokyo) was the capital of Japan.

Girls’ and boys’ processes of growing up were structured by ceremonies that brought families and the wider community together. Changes in dress and hair style typically marked children’s movement from one stage of childhood to the next. Knowledge about such childhood transition markers can be crucial for all those working with visual sources about children in early modern Japan.

The birth of a child was a usually joyful event, even if associated with mixed feelings of anxiety whether the mother and child are going to survive. Births usually took place in a room or structure outside the usual living area. Depending on the mother’s social status this room was then furnished or not. For example, we know that the birthing chambers of imperial mothers were furnished entirely in white and decorated with a folding screen with images that are associated with longevity, such as the crane, the pine, the tortoise and bamboo. The baby’s birth was usually followed one week later by a naming ceremony. Children’s names in premodern Japan depended on their gender and social status. The majority of girls only received one given name and kept this name throughout their adult lives. By contrast, boys kept their given name (yōmei 幼名) only until they reached formal adult status.

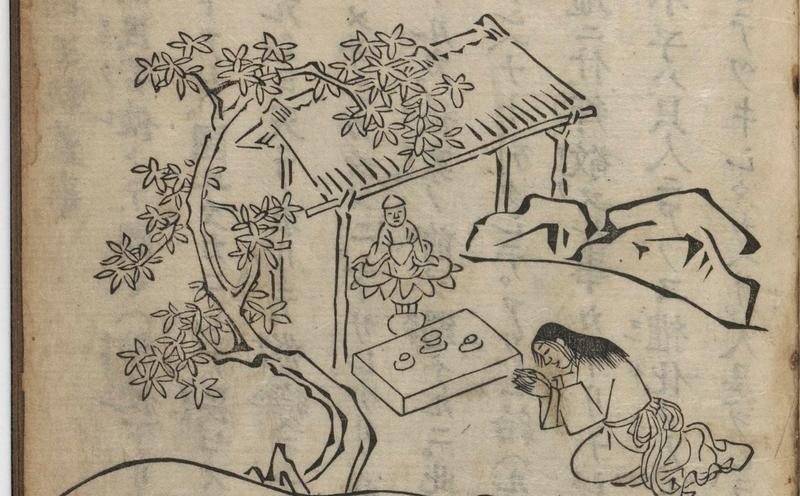

During their various stages of childhood, Japanese children’s hair style changed. Importantly, in early modern Japan children’s biological age was not counted according to their birthdays, but according to the lunar calendar. Thus at birth, a child was one sai 歳. Everyone would turn one sai older with the start of a new calendar year, even if they had been born at the end of the twelfth lunar month. During the first two to three years of their lives, children’s hair was shaved. The kamioki髪置 (‘hair-placing’)- ceremony then marked the onset of substantial hair growth (see illustration 1). This was usually accompanied by prayer for a long life without diseases. The next rite of passage was the so-called himotoki 紐解 (undoing the strings) ceremony during which boys at around the age of five sai and girls at around the age of seven sai, exchanged the string that held their kosode garments together with an obi.

Illustration 1: The little boy Kōya Daishi prays in front of a temple he made by himself. His hair is already growing, but his garments are still held together by a string rather than an obi. Detail from Kōya daishi gyōjō zuga 高野大師行状図画, Vol. 1, FSC-GR-780.803.1-10, early 17th century, The Smithsonian Institution

Hakamagi 袴着 was the ceremony for wearing hakama (pleated trousers) for the first time. This rite of passage was during the Tokugawa period reserved for boys from aristocratic and warrior families. At this point, boys were between the ages of ten or twelve sai. Samurai girls’ clothes normally changed after their first marriage. This rite was called sodetome 袖止 (‘stopping the sleeves’) and involved a shortening of their long kimono sleeves. Importantly, the sodetome ceremony, and thus first marriage, also signified samurai girls’ transition into social adulthood. By contrast, boys did not need to get married to become social adults. Instead, they went through a public ceremony, called genpuku 元服 (coming of age), during which samurai boys received a typical male adult topknot hairstyle. The genpuku ceremony of samurai boys usually took place when they were between sixteen and seventeen sai. Significantly it was also only from their seventeenth calendar year onwards that a young samurai had the legal right to adopt an heir in order to secure household continuity. Apart from the above described childhood transition markers in samurai households, there also existed particular rites and transition markers for girls and boys of the upper aristocracy as well as those children who entered Buddhist monasteries as novices. Moreover there may have been a variety of local transition markers in rural settings across the country. Gender, status, age and locality thus shaped how adults, and possibly also children themselves, marked young peoples’ ‘trajectories’ towards social adulthood.

However, Edo period samurai transition markers – such as kamioki, himotoki and hakamagi describe above – are of particular interest, because as upper-class rites they were eventually in the eighteenth to nineteenth centuries popularized among commoners as shichi-go-san (seven-five-three) celebration (see illustrations 2 and 3). The celebration has this name because parents and guardians take their seven- and three-years old girls as well as their five years olds boys to a popular Shinto shrine to venerate the deities and to ask for their protection for their children. On this occasion, girls usually wear an obi for the first time and little boys hakama. Being first associated with the capital Edo/Tokyo, by the mid-twentieth century, shichi-go-san was known and practised all over Japan.

Illustration 3: Going to the Shrine for the Hakamagi Ceremony at the Shichigosan Festival, Chōkyōsai Eiri, about 1788-1790, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Illustration 2: Going to the Shrine for the Obitoki Ceremony at the Shichigosan Festival, Chōkyōsai Eiri, about 1788-1790, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston