Blind Children in Late Ottoman Istanbul: A Glimpse through Education and Welfare Policies

İrem Yıldız is a DPhil candidate in the Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies at St. Antony’s College, Oxford. Her fields of interest include the history of disability, medicine, childhood studies, and museum studies in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries Ottoman Empire and the Middle East. Her research has been supported by a variety of institutions, including Koç University’s Research Center for Anatolian Civilizations Junior Fellowship (2021–22), Istanbul Research Institute’s Travel Grant, Harvard University’s Houghton Library Rodney G. Dennis Fellowship (2022–23), University of Oxford’s St. Antony’s College and the Department of Oriental Studies Research Grants.

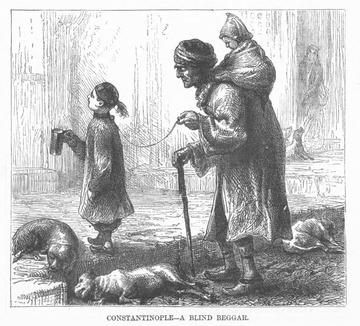

On 13 May 1876, Harper’s Weekly Magazine published an article entitled “Constantinople” that, it claimed, offered insight into daily life in the city. The writer stated that “Constantinople, that world-renowned city of the Bosphorus, can only preserve through distance and perspective her ancient reputation for beauty. On near approach the charm vanishes: the palaces prove to be only dilapidated barracks, the minarets nothing but large whitewashed pillars, and the streets, steep and narrow […].”[i] The writer viewed the city of Istanbul as one whose beauty has vanished, whose architecture does not give pleasure. The article focuses instead on “the ugliness of the streets of Constantinople” with four sketches showing daily people working in the public space. In these drawings, one sees the meat seller, someone waiting for dinner, the scavenger, and the blind beggar. The last sketch — the blind beggar — shows a blind old man, carrying an infant on his back and holding a string that is roped around the neck of another child who walks in front, leading him by means of the string while holding a cup to collect money.

Harper’s Weekly, “Constantinople,” Harper’s Weekly: Journal of Civilization, May 13, 1876, 399

The derogatory phrase used with reference to visual impairment – ‘blind beggar’ – had a ‘factual’ historical connotation during the late Ottoman Empire. Orientalist travellers who visited various towns of Istanbul during the late nineteenth century vividly recorded a perceived link between visual impairment and begging/poverty. Thus, the term ‘blind beggar’ became a descriptive category widely used by orientalist travellers to describe daily life in Istanbul during the nineteenth century.

The literature on poverty and charity inevitably encompasses the history of childhood and the politics of child welfare in the late Ottoman Empire. The edited volume Poverty and Charity in Middle Eastern Contexts (2003) provides a glimpse of the historical relationship between the practices of poverty and philanthropic activities in the Islamic world, stretching across the medieval period to the late nineteenth century. The book draws attention to the conditions of the poor, and their relationships with the state and ruling elites behind the charitable institutions. Following the history of childhood studies, Nazan Maksudyan’s Orphans and Destitute Children in the Late Ottoman Empire (2014) surveys the social history of childhood in the Ottoman Empire by focusing on narratives surrounding the history of destitute and orphaned children. Maksudyan explores imperial educational policies and Hamidian charity/welfare policies toward children from the perspective of ‘history from below’. My question is: how does this growing field — childhood studies — contribute to writing the history of disabled children in relation to the politics of welfare and education during the late Ottoman Istanbul?

Concern about the visibility of disabled individuals in the urban environment, particularly the blind poor non-Istanbulites, grew substantially in the second half of the nineteenth century. The migration of poor and sick refugees became a significant threat to the Ottoman state and society more broadly, since many of the migrants/refugees ended up begging on the streets of Istanbul. Migration from the countryside into Istanbul led also to an increase in poverty and begging[ii] among blind poor individuals. Responding to these population movements and demographic transformations, the Ottoman government utilized institutional and legal means to create and employ new modes of municipal governance, including the development of street alignment, paving and lighting ordinances, and further legal actions to control public hygiene, crime, prostitution, street begging, and immigration. By tying these two transformations together – changing demographics and the evolving nature of municipal management – we can see more clearly how municipal reforms in the Ottoman Empire, and in particular the urban history of Istanbul, was at least in part a reaction of urban government to the increased mobility of blind beggars.

As Nora Lafi writes, after the arrival of migrants in town, “the very urban system becomes the object of a dynamic interaction with a new element that might modify it, or, in the absence of any modification, reveal its inertia.”[iii] With this dynamic interaction between locals and disabled migrants, the Istanbul municipality was forced to modify its urban environment while controlling the movement of blind beggars (particularly children) in the city. These changes in urban structure pushed the Ottoman state to offer assistance and aid particularly for disabled poor migrants.

Following large-scale population movements in the mid-nineteenth century, the institutional and legal character of the Ottoman government led to the creation of municipalities and new modes of governance, particularly the introduction of the Municipal Regulation of 1868 and the Municipal Law of 1877. They gave municipalities full authority to regularize the city of Istanbul, which aimed not only at ordering the buildings, roads, and quays, and constructing water and sewage lines,[iv] but more importantly ordering the streets where the blind beggars were living, walking, and strolling around Istanbul.

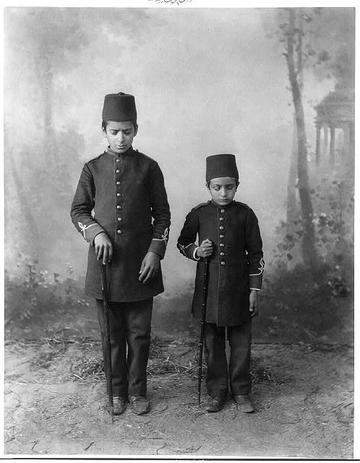

These regulations gave municipalities the power to control and monitor schools for blind, mute, orphan, and destitute children. On 14 June 1889, and following these regulations, the Minister of Education Münif Pasha established a special school to train deaf-mute children. This was new a school built specifically for hearing- and speaking-impaired children as a component of the Hamidiye School of Trade (Hamidiye Ticaret Mektebi). It provided language courses (in particular Turkish and French), artistic courses (such as writing and painting), physical activities, maths, and accounting courses.[v] On 28 February 1891, Münif Pasha proposed to establish another school in Istanbul particularly for blind students. About two weeks later, on 17 March 1891, the School for the Blind was founded as a part of the School for the Deaf and Mute (which later changed its name to the School for the Deaf, Mute, and Blind).[vi] Visually impaired students took courses focusing on social and numerical sciences including Turkish and French, music, history, geography, and accounting. With the support of Münif Pasha and Ferdinand Gratin, who was the Austrian accounting officer and the director of the Deaf and Mute School in Istanbul, the School for the Blind gained a positive reputation as the earliest special school for blind children in Istanbul. In later years, however, the school began to lose its reputation due to its financial problems.

Over the past two decades, the history of charity and education towards children have become rapidly growing fields in Ottoman studies. Despite a large literature on the history of philanthropic activities, there is a historiographical gap that needs to be filled by including the history of special education in the late Ottoman Empire. I argue that blindness in late Ottoman society cannot be understood without examining the regulations and institutions of the Hamidian era’s public education system, particularly the establishment and subsequent demise of the School for Deaf, Mute, and Blind in Istanbul. Thus, in my thesis, I aim to present the attempts to restructure disabled practices towards visually impaired children in the Ottoman state and society through education, regulation, and institutional changes.

Abdullah Frères. A Photograph of Students, the School for the Blind, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Abdul Hamid II Photograph Collection Washington, D.C., Album 9531, no. 6. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2001700183/

[i] Harper’s Weekly, “Constantinople,” Harper’s Weekly: Journal of Civilization, May 13, 1876.

[ii] Fariba Zarinebaf, Crime and Punishment in Istanbul, 1700-1800 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010), 46.

[iii] Nora Lafi, “The Ottoman Urban Governance of Migrations and the Stakes of Modernity,” in The City in the Ottoman Empire: Migration and the Making of Urban Modernity, ed. Ulrike Freitag et al. (New York: Routledge, 2011), 12.

[iv] Zeynep Çelik, The Remaking of Istanbul: Portrait of an Ottoman City in the Nineteenth Century (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), 47.

[v] Sezai Balcı, Osmanlı Devleti’nde Engelliler ve Engelli Eğitimi: Sağır Dilsiz ve Körler Mektebi [The Disabled in the Ottoman Empire and Education of the Disabled: The School for Deaf, Mute and Blind] (Istanbul: Libra Kitapçılık ve Yayıncılık, 2013), 125.

[vi] Mualla Erkılıç, “Developments in Disability Issues during the Late Ottoman Period of Turkish History from 1876 to 1909,” in The Routledge History of Disability, ed. Roy Hanes, Ivan Brown, and Nancy E. Hansen (London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2018), 61–66.