A synthesis of all the presentations made and questions raised suggests the intersections of hair and gender extended further than the traditional association of the beard or moustache with masculinity.

Annabelle Grigg studies History at St Peter’s College and plans to graduate in 2022. She is currently working on her thesis, exploring the relationship between gender, hair and trade in early modern England. Outside of her studies she enjoys editing and writing for different student zines and news publications.

Portrait of Bartolomeo Panciatichi by Agnolo di Cosimo, known as Bronzino, 1540. Uffizi Gallery of Florence, Italy.

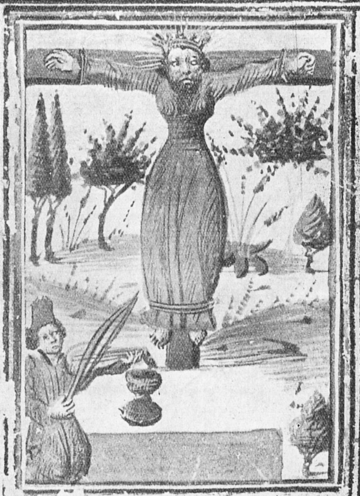

Wilgefortis, anonymous Illumination from a Flemish Book of Hours, 1415. University Library, Ghent.

Swapping hairstyles and grooming techniques today might seem no more than passing fads; but shaving or growing beards in the past was not so casual a choice. Facial hair can be viewed as one of the most significant factors in the construction of historical gendered identities in particular, manhood and masculinity: indeed until the eighteenth century it was tough for men to grow beards before the age of 24. Like other body parts, hair was and still is an important site of representation, where group identity is constructed and individual subjectivity is experienced.

On the 4th March 2021, over fifty academics, graduate and undergraduate students gathered to share their findings on the intriguing and varied relationship between facial hair and gender identities, including Dr Stefan Hanß from Manchester University and Professor Peter Marshall from Warwick University. Undergraduates also presented papers, resulting in an eclectic collection of different case studies from drag kings, tonsured priests, bearded witches to moustached military men and exciting collaborations from individuals at varying stages of their academic careers.

This diversity was replicated in the research displayed. Across all the presentations, a strong sense of the expansive utility of beards emerged, forming different political regimes, religious groups and cultural belonging. For example, Professor Lesley Abrams discussion of the Viking Beard highlighted some of the of hair in literature from nomenclature to mythological stories. Parallels were later made in the study of the repeated presence of beards and anxieties about the absence of beards in early modern theatre, as with the female witches in Shakespeare’s Macbeth.

The event was strongly cross-disciplinary. Facial hair was often intimately related to visual forms of self-presentation, so a range of different images and aspects of material culture were consulted. For instance, Dr Hannah Skoda’s research into the famous bearded female Saint Wilgefortis showed her in different statues and manuscript illuminations in the fourteenth century. Unpicking the visual symbolism of a bearded pious feminine figure, Skoda raised questions about the role of beards in creating identities other than masculinity.

A synthesis of all the presentations made and questions raised suggests the intersections of hair and gender extended further than the traditional association of the beard or moustache with masculinity. Rather than just being an issue of gender policing or manhood, the beard often resisted singular categorisation, also expressing female, trans and non-binary identities too, further disrupting ideas of neat gender binary categories and inviting future study.

Annabelle Grigg

St Peter’s College, Second Year Undergraduate

This event was run as part of the Theme Paper 'Masculinity and its Discontents, 200-2000', one of the Outline Papers taught in the second/third year in the 'European and World History' component of the BA in History.