Mapping Historic Oxford

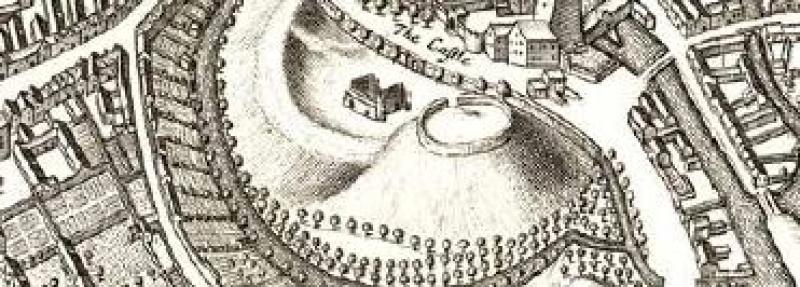

Oxford Castle on David Loggan’s map, 1675.

The Historic Towns Trust

In January this year the Divinity School saw a celebration to mark the publication of an Historical Map of Oxford: the work of a team of historians and cartographers, themselves successors to an impressive array of Oxford antiquarians and topographers who have struggled to excavate, record and map the origins and development of the Saxon burgh into a medieval University town and, later, into a factory city.

Alan Crossley and his team (Anne Dodd, Malcolm Graham and Julian Munby) have been walking over well-trodden paths. It was the land surveyor, Ralph Agas who first mapped Oxford in 1578, looking down on the city from the north as from the air. In the following century the remarkable antiquarian Anthony Wood, working in conjunction (if not always harmoniously) with the engraver, David Loggan collected an immense amount of material relating to the city. Wood brought out his two volumes on the History and Antiquities of the University of Oxford in 1674 and in the following year Loggan’s Oxonia Illustrata was published. Loggan’s meticulous and detailed views of the colleges, gardens and university buildings, together with a map of the city, were outstanding not only for their accuracy, but also for their style. Wood’s scholarly work and Loggan’s skilled draughtsmanship have remained the essential starting point for all later histories and mapping of the city. But for the less distinguished civic buildings, such as tenements and pubs, the historical map-maker can turn to the invaluable work of H.E.Salter (1863–1951) who studied and published the deeds relating to city properties to be found among the archives of the various Oxford colleges. Using this material he was able to construct detailed histories of numerous house-sites over several centuries in a way that had not then been attempted for any other city (although much imitated since).

The new historical map of Oxford draws upon the research and draughtsmanship of these earlier scholars and artists, but brings to the understanding of the historic city, the skills of modern cartography. The key medieval and post-medieval buildings have been plotted onto the first properly surveyed Ordnance Survey 1:2500 map of the city made in 1876. The new historical map charts the continuing evolution, through destruction, rebuilding and redevelopment, of a town which evolved from an important Anglo-Saxon shire town into a city because a great university grew up at its centre. This map shows not only the medieval and later buildings that were standing in 1876, but also indicates the sites of the lost earlier buildings. The map also shows how the Victorian developments (the city grew from 12,000 people in 1800 to nearly 35,000 by the time the map was surveyed) were grafted onto the medieval university county town. Suburban developments to house workers at the University Press, the Eagle Foundry, the Lion and Swan Breweries (later Morrells) and in the expanding university itself can be seen leaching out to the west and south of the city. The economic prosperity of Oxford was fostered by the canal which reached the town in 1790 and by the two railway lines which were operating by 1852. The new map provides on its reverse a gazetteer with a brief account of all the buildings and sites on the map and Alan Crossley has also supplied a succinct overview of the development of the town.

This new historical map of Oxford is sponsored by the Historic Towns Trust which began life as ‘The British Committee of Historic Towns’ set up in Oxford in 1957 under the chairmanship of Professor Sir Ian Richmond and with Mrs Mary (Roddy) Lobel as the General Editor. The British Committee was part of the International Commission for the History of Towns set up in 1955 to encourage the production of a series of atlases of historic European Towns: their development was to be mapped to standard scales so that common patterns of topographic development might be compared, and common themes might emerge. The Commission included representatives from all European countries west of the iron curtain, but it extended also to Poland and Hungary. This drawing together of European countries in the aftermath of the Second World War found expression in a number of common ventures, of which the mapping of historic towns was one.

Mrs Lobel recruited a strong Oxford contingent on her committee under the chairmanship of Sir Ian Richmond, including the historians Trevor Aston and Barbara Harvey and the historical geographer William (Billy) Gilbert. The first volume of eight maps was published in 1969 and included Caernarvon, Glasgow, Nottingham and Salisbury. By the time a second volume of maps was produced in 1973 the Historic Towns Trust had been set up to help to finance the enterprise, and Mrs Lobel gathered three Oxford luminaries to act as Trustees: Lord Franks, Dame Lucy Sutherland and Walter Oakeshott — all heads of Oxford Colleges. The Committee was now chaired by Billy Pantin. On his death in 1973 Martin Biddle took over briefly, followed from 1977 to 1994 by Asa Briggs and subsequently, until 2013, by Martin Biddle again, and now by Keith Lilley. For many years Colin Roberts of the Oxford University Press, together with James Campbell of Worcester as secretary and Sir Kenneth Wheare as treasurer, were the key figures on the committee. Needless to say Mrs Lobel continued to act as the General Editor inspiring exasperation and admiration in equal measure.

Roddy Lobel had been an undergraduate at St Hugh’s and remained in the Oxford orbit for the rest of her life. She was married to the distinguished but reclusive papyrologist, Edgar Lobel who regularly dined in his college, Queen’s, in order to save ‘his lamb’ from having to prepare a proper meal. Whether she would have been able to do so in the medieval conditions of their house in Merton Street is doubtful. In 1935 Roddy published her BLitt thesis, an account of the borough of Bury St Edmunds which remains to this day the best history of the town. When Salter became the Editor of the revived Victoria County History of Oxfordshire, Roddy was appointed his assistant and then succeeded him as Editor in 1948. The volume on the History of the University of Oxford which appeared in 1954 was largely their joint work. But in 1966 Roddy abandoned the Victoria County History in order to give her full attention to the Historic Towns Atlas which now became the prime focus for her intellectual (and to some extent also her emotional) life.

The faithful ally of Roddy Lobel in this enterprise was Colonel Henry Johns, who was the self-styled ‘Topographical Mapping Editor’ for the project. He was a remarkable man who drove a bright yellow open sports car and although looked and sounded like Colonel Blimp, he was an intellectual force to be reckoned with. He had joined the army in 1929 working as a surveyor, saw active service in the second World War when he escaped from Dunkirk, was posted to Egypt, but was captured by the Germans and escaped again to resume his surveying work in Egypt, and then in Thailand and Germany. When he retired from the army in 1962 he was recruited by the Oxford University Press to promote their sales of maps. Here he encountered Roddy who was anxious that the OUP should publish the Historic Towns Atlases. When they refused to do this, Henry Johns resigned and in 1965 set up his own cartographic firm in King Edward Street in Oxford with the express purpose of carrying out mapping for the Historic Towns Trust. It says much for Roddy’s powers of persuasion that Henry Johns took this risk: and risk it was. He poured all his money into the venture and although he was paid for his remarkable work the firm was only kept afloat by Henry’s own injections of funds. The firm has however survived as Lovell Johns Ltd based in Long Hanborough; and they are still connected with the Historic Towns Atlas. Henry Johns was a remarkable designer of historic maps: he had a real understanding of sites and buildings and he knew how to present them on paper; his work was beautiful as well as scholarly. But his methods were unorthodox and, perhaps, instinctive, and his account of his work to be found in the London atlas, published in 1989, does little to clarify his methods of working. But work they did, and those who collaborated with him admired and, indeed, loved him.

He and Roddy Lobel formed a remarkable team: each faithful to the other’s vision of the work to be done, while pursuing the same ends by different means. Their loyalty and commitment were touching if, on occasion, enraging. There was a gap of fourteen years between the publication of the second atlas volume and the London volume in 1989. By this time Roddy was eighty-nine years old and Henry was seventy-five. They both died in 1993 and without the driving force of these two remarkable people, no further atlases appeared until 2015 although work on various towns ( Winchester, York and, later, Oxford) continued to make slow and scholarly progress. But thanks to a generous legacy from Roddy Lobel and notably to the skills of the new cartographic editor, Giles Darkes, who was appointed in 2008, the enterprise has sprung into life: two portfolio atlases have now been published (Windsor and Eton, and York) and Winchester and Oxford will soon follow. Other towns are now jostling to be included in the series. Moreover, as popular supplements to the portfolio atlases, the committee has also published folding historical sheet maps of London in 1520, York, Winchester, Windsor and Eton, and now Oxford.

It is fitting that Oxford, where the Historic Towns Committee was first established and nurtured by so many Oxford historians should at last have its own historical map. This can be bought from most bookshops in Oxford, the Bodleian’s shop and the Oxford Museum in the Town Hall, or ordered online. It has proved to be immensely popular and the first printing of 1000 copies has already sold out and has been reprinted. Meanwhile the Historic Towns Committee is working hard to complete the research and mapping for the Oxford Atlas volume from which the folding historical map is derived, and to raise the funds necessary for its publication. If you would like to help with this enterprise, please look at our website www.historictownsatlas.org.uk.

- Caroline Barron

Professor Emerita

Royal Holloway, London