The Vessels of Memory: Mediating Official and Cultural Narratives of the Holocaust in the Classroom

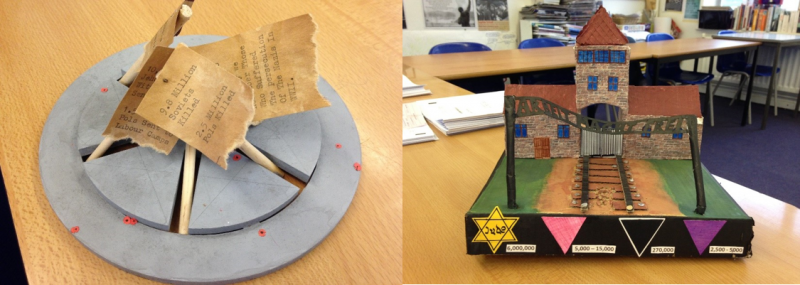

Memorials made by 15-year-old pupils as homework for History course

What constitutes collective memory, and where should we look for it? My doctoral thesis aims to comprehend humanities teachers’ memory of the Holocaust, who have functioned as both ‘makers’ and ‘consumers’ of official and cultural historical memories. Last year, my Masters research attempted to track the evolution of Holocaust education from historical lessons in the 1990s to emotive, emphatic lessons since the Stockholm Declaration in 2000 and the establishment of Holocaust Memorial Day in 2001. My Oral History interviews with history teachers in Oxford suggested teachers themselves acted as fundamental mediators of memory; they were influenced by cultural, familial or personal memories of the Holocaust as much as they were by textbooks or official guidelines. For example, Claire, a teacher from Oxford, said her father-in-law’s experiences liberating Belsen informed her understanding; another history teacher, Elaine, suggested she was exceptional in her approach, as she was much influenced by a year spent volunteering in Israel in her twenties; Katy, a teacher from Reading remembered the Holocaust from a novel,

“I can’t remember ever being taught anything about Nazi Germany to be honest…. I think it was probably a book. At school I used to read a lot of historical fiction. [When] Hitler stole Pink Rabbit… and then I would have got to the age of watching Schindler’s List.”

Child Survivors of Auschwitz

Teachers themselves are very much a ‘black box’ who consume historical memories from literature, newspapers, cinema, conversation as well as, their education and personal background which are later synthesised and juxtaposed with official ‘textbook’ narratives in the classroom. Yet, teachers have so far been bypassed in the study of historical memory. Though many historians have analysed textbooks, these studies scrutinise only one type of national historical narrative, and are thus a narrow frame of historical memory. Teachers are shaped by personal, regional, national and global memories of the Holocaust, as well as shifts in historiography. I intend to explore which of these ‘conduits of memory’ have been implemented in the classroom, and how these sources of memory and history have changed over time.

In British Holocaust education, official narratives have been channelled through textbooks, resources and teacher training sessions. Since the Stockholm Declaration in 2000, guidance on how to teach the Holocaust has been set by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance. In the UK, schools have been obliged to provide Holocaust education for pupils typically aged 13 since the introduction of the National Curriculum in 1991. Whilst this was once the undisputed territory of the history teacher, many schools transferred the subject to English departments after 2006 to address it through the novel and film The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas which attempts to see the Holocaust through the eyes of a child. It tells the story of Bruno, the son of the SS Commander of Out-With, a fictional Auschwitz, who befriends Shmuel, a Jewish prisoner of the camp. When Shmuel’s father disappears from the camp, Bruno slips under the barbed-wire fence to look for him. The story concludes with the roundup of the two boys and their march to the gas chambers, where they die hand-in-hand. Whilst the book and film adopts the expected imagery of the Holocaust, such as barbed wire, gas chambers and striped uniforms, it is ultimately an implausible story, leading pupils to false conclusions about the simplicity of moral decisions and the narrative of the Holocaust. Gray’s research shows that some pupils believe the Holocaust only happened in Auschwitz and terminated after an SS-Guard acquired a moral awakening following his son’s accidental death in the gas chambers.[1]

The reliance on cultural representations has altered teaching objectives to use Holocaust education as a unique opportunity to teach other skills, primarily empathy. In contrast to other historical periods studied in schools, the Holocaust has emerged as a public discourse in which memory has outpaced history. Though the written word of the historian has provided both limits and structure to discussion in the classroom, the sources of dialogue stem from cultural memory. The historian’s account is not referenced by the teacher, but instead the teacher’s experience of the Holocaust is through photographs, films, books, testimonies. It is exemplified in history teacher Katy’s lesson,

“I take people’s shoes off them when they enter the room and we play guess the shoe. And it’s very light hearted and its very fun. And they are all laughing. But then I put the picture [of shoes in Auschwitz] up on the board and from that we tease out... and the mood changes, it shifts and they start to see the importance a bit more.”

The trauma of the Holocaust cannot be recreated in the classroom, but is dominated by ‘living’ narratives which preceded teachers’ birth, demanding an emotive and respectful response. As Elaine, a teacher who had opted to attend a number of Holocaust education training sessions run by the Holocaust Educational Trust, commented,

“I have never shown a picture of dead bodies in a pile. Now I know teachers do... they think that’s the way to convey the horror to the children and I have just never done that. I’ve never shown piles of bodies, because I think all of the things I’ve read [about respecting victims].’’

There is an added moral imperative in teaching the history of the Holocaust in the UK, partly directed by Holocaust educational or memorial organisations, but even more by cultural memory, which has been more powerful and useful to teachers than historical narratives inside textbooks. Next year my Oral History project takes me abroad to Aix-en-Provence in southern France and Linz in Upper Austria. Both cities border concentration camps which were recently reopened as educational centres. Teachers’ memory of the Holocaust may prove more entangled in Aix-en-Provence, where a Jewish community prospered in the Second Republic but were murdered in the Vichy regime, and in Linz, where entire industries and neighbourhoods were built by the prisoners of Mauthausen. I aim to disentangle local, national, global and personal memories of the Holocaust.

- Heather Mann

Interviews with teachers, conducted by Heather Mann, Oxford, 2016; in the author’s possession

[1] M. Gray, Contemporary Debates in Holocaust Education, (London, 2013), pp. 7-9